(Alicia Patterson Reporter, Summer 2008)

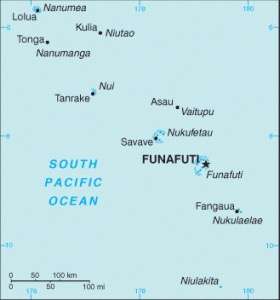

WELLINGTON, New Zealand — On October 1, 1975, the British colony of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands officially split in two, with the nine small coral atolls of the Ellice Islands reclaiming their traditional name of Tuvalu.

Exactly three years later, a new flag rose over the capital of Funafuti, with the Union Jack relegated to the upper left-hand corner and the rest a light blue field featuring nine yellow stars arranged in the shape of the new nation. The ceremonies that night included fireworks, champagne, a show of traditional dance, and salutes fired from American, British and Australian ships there for just that purpose. That night, after more than 80 years under the crown, Tuvalu began its life as an independent nation.

Tuvalu’s birth was a model of self-determination, made possible when 92 percent of the islands’ mostly Polynesian citizens backed a referendum to separate from the mostly Micronesian Gilberts (which became independent Kiribati in 1980).

At the time of independence, Tuvalu had no telephones, no television, and only a single-digit number of cars. Since then, life there has changed considerably. More than 1,300 cellular phones now operate on the atolls, while a similar number of people have regular Internet access. Eight years ago, the country signed a high-profile deal to sell the rights to its .tv web address for $50 million, nearly five times its annual gross domestic product at the time. That money helped the country expand its electrical service and better fund its educational system. Also, finally making enough money to afford the entrance fee, the world’s least populated nation outside the Vatican City joined the United Nations a year later.

For all the advantages Tuvalu has gained in recent years, though, what it doesn’t have is certainty about its future. There are myriad reasons for pessimism, all driven by the side effects of global warming. It’s only a matter of when, not if, the entire nation of roughly 11,000 people will have to relocate as its land becomes increasingly uninhabitable.

The ever-rising sea level is the most immediate threat. At its highest point, Tuvalu sits only 15 feet (4.5 meters) above sea level – only the similarly imperiled Maldives islands in the Indian Ocean lie lower – and much of the country rests considerably closer to the water level. Most Tuvaluans live at about half that altitude.

There’s a big range in predictions about how high the oceans will rise, but none are exactly encouraging. In 2001, the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted a rise between 9 and 88 centimeters before the end of this century. Last year, though, it revised that prediction to between 28 and 43 centimeters. A gauge installed in Tuvalu by Australian researchers has recorded an average rise of 0.6 centimeters each year since 1993 – meaning the cumulative rise has taken just 15 years to top the IPCC’s initial low-end estimate for a full century. With scientists generally setting 20 centimeters as the level at which islands like Tuvalu’s become uninhabitable, time isn’t on their side.

The combination of low-lying land and ever-rising water means regular flooding is a fact of life for Tuvaluans. And it’s getting worse. “King Tide” arrives on schedule every February, flooding homes and roads while damaging infrastructure. In 2000, tides reaching 3.2 meters (10.5 feet) knocked out all international phone service to the islands for days. Another tide of 3.48 meters (11.4 feet) hit on the last day of February 2006.

Five of Tuvalu’s nine islands – including Funafuti, which houses about half the country’s population of about 11,000 – are coral atolls. They formed when rings of coral surrounded ocean volcanoes and gradually grew as the land in the middle subsided. What’s left are basically rings of coral on which Tuvaluans live, built around lagoons that provide the fresh water people need to survive. The atolls are not only low but also extremely narrow. Tightly packed Funafuti is only 600 meters (0.37 miles) across at its widest point – and most of its land is narrow enough that both the surrounding ocean and central lagoon are visible at the same time from the strip between them. That area keeps shrinking further thanks to cyclones that carry chunks of it off to sea – in 1997, researchers found two recent storms had combined to reduce the country’s landmass by nearly 7 percent. Warming waters make prime breeding grounds for such storms.

Such a narrow landscape means massive tides can cover most of Tuvalu with water when they hit. They also leave behind a major problem when they recede.

“Freshwater lagoons are essentially formed because the rainwater percolates into the sand and gravel and makes up the islets,” explains archeologist Marshall Weisler, a professor at the University of Queensland who studies atolls in Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Solomon Islands. “The fresh water you see exposed on the surface is because the elevation of the soil is quite low and it’s exposing the freshwater lens that’s sitting on top of the sea water that’s under the islet.

“The freshwater lens can be disrupted if there were high surf or high storms that deposited saltwater inland,” Weisler says. “That water would sit on top of the freshwater lens before gravity sorts that out. It’s like taking a bottle of oil and vinegar and shaking it up – it’s all the same at first, and then over time it will separate out again. How long that takes on a low coral island where the freshwater lens has been disturbed will also take time.”

Tuvalu has no streams or rivers, so the lagoons are its only sources of fresh water (and even that water must be desalinated before people can safely drink it). With no arable land, no forests and no pastureland, the only way to grow any crops is to plant taro and other root vegetables in holes dug at the right depth to tap into the groundwater. Too much salination, and even that becomes untenable.

Faced with all these problems, migration has become an obvious solution. Thousands of Tuvaluans have become de facto refugees, even though no nation will officially give them that status.

“Tuvalu is likely to be one of the first countries to become uninhabitable and is already starting to experience the need for people to move,” says Peter Cotton of RMS Refugee Resettlement, a non-governmental organization tasked with resettling refugees in New Zealand. “Yet we’re in a world in which the UN has been almost paranoid about the use of the term ‘environmental refugees’; they don’t like the term. And they certainly haven’t been prepared to really discuss it.

“If we look at where environmental refugees might take us in terms of numbers in the future, it seems to me that potentially rapid climate change could force greater flows of migration than we’ve ever witnessed.”

Even before becoming a UN member, Tuvalu began actively lobbying its neighbors to start taking in its soon-to-be-homeless citizens, with limited success.

In 2001, John Howard’s Australian government rejected Tuvaluan overtures, continuing a pattern of resistance to immigration and climate-change concerns. (His recently elected successor, Kevin Rudd, has yet to announce his position on the issue, but has ratified the Kyoto Protocol on reducing greenhouse gases).

The island state of Niue has been the most welcoming, as its sole atoll has seen its population drop significantly since the 1960s, creating a demand for workers. Though the country is self-governing, Niue has a free-association relationship in which Niueans are also citizens of New Zealand, so many have chosen to move there. There are now nearly seven times as many Niueans in New Zealand as in Niue itself.

That’s a record Tuvalu would like to emulate, though its migration relationship with New Zealand is best described as complicated.

Between 1990 and 2001, the Tuvaluan population in New Zealand more than doubled, passing the 2,000-person mark. The most recent Kiwi census, taken in 2006, showed a 34 percent increase from 2001. By that time, 2,625 self-identified Tuvaluans lived in the country 4,000 kilometers south of their homeland, with four of every five residing near Auckland – a logical fit given the city has a larger Polynesian population than any other in the world.

Around that same time, then-Prime Minister Ionatana Ionatana appealed to his New Zealand counterpart, Helen Clark, far an agreement to gradually take his country’s entire population. While hundreds of news stories in New Zealand and world publications have reported an “understanding” that it was willing to absorb the whole of Tuvalu’s population if waters keep rising, “New Zealand does not have an explicit policy to accept people from Pacific island countries due to climate change,” a Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson says.

Still, New Zealand has started taking in more Tuvaluans. In 2001, the immigration department introduced the Pacific Access Category, allotting a guaranteed annual quota of 75 spots for Tuvaluans (plus their spouses and children) among its 375 total places for eligible South Pacific islanders – with English skills and a job offer among the requirements for entry. In late 2006, the government created an additional temporary work scheme, the Recognized Seasonal Employee policy. And a smaller number of Tuvaluans are also applying through the standard immigration process.

So, migration is already a reality for many. But with so few destinations willing to take them and so few quota spots in those countries, the people of Tuvalu know there are more of them than there are available spots for sanctuary at the moment.

And still the water around them keeps rising.

© 2008 Jeff Fleischer

Jeff Fleischer, a Chicago journalist and author, is examining the fate of Tuvalu, the Pacific atoll that is the world’s most likely nation to be subsumed by water due to climate change.