In a Strange Land

August, 2008 – BAY OF PLENTY, New Zealand – Of all the adjustments she’s had to make since arriving in New Zealand, Annabelle Lolo Palota says one of the biggest struggles has been getting acclimatized to the climate.

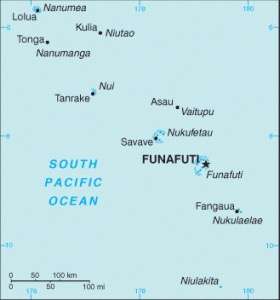

It’s no small change. In her homeland, the South Pacific atoll nation Tuvalu, temperatures rarely dip below the upper 80s. In the New Zealand winter, though, it routinely gets 30 to 40 degrees colder than that. On a winter day, she wears multiple layers of sweats and fights back sniffles and coughs brought on by one of several colds she’s acquired since arriving here.

“The first time I ever saw the frost was when we were working down near Hastings,” she says. “All the Tuvalu people were outside our window going, ‘Wow, this is ice. It’s just like opening a refrigerator.’ We could see the tops of the mountains, so white. We were all wanting to actually go over there and stand on the ice, but we didn’t get a chance.”

Palota has joined an increasing number of Tuvaluans earning their incomes abroad. Now working in a kiwifruit pack house in Te Puke, she is one of a group of 35 Tuvaluan workers who came here to New Zealand in early March as part of this country’s new Recognized Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme. That group was the first from Tuvalu to participate in the program.

Announced in late 2006 and partly developed in response to requests from a number of South Pacific nations, the RSE allows approved employers in New Zealand’s horticulture and viticulture industries to recruit islanders for short-term employment. Tuvalu joined Samoa, Tonga, Kiribati and Vanuatu as the first wave of nations participating, with Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea also expecting to provide labor under the scheme. Employees brought here from most countries under the RSE are allowed to stay for terms of up to seven months, though Tuvalu’s specific arrangement allows for up to nine.

It’s a program the government of Tuvalu has long lobbied for, hoping it will provide its citizens with better earnings to bring home with them, as well as job skills.

“Gaining an income for Tuvaluans by spending a short time in employment is certainly a boost to the income of the people and the economy of Tuvalu,” says Ian Fry, advisor to the Environment Department of Tuvalu. “Because employment opportunities in Tuvalu itself are fairly limited. Giving them the opportunity to work overseas for short time periods certainly gives them some sort of economic boost.”

For workers, it also provides experience earning abroad – experience that will likely prove valuable for those planning to migrate. Even more so if, as expected, Tuvaluans ultimately have to migrate en masse. With its highest point only about 15 feet above sea level, and most of its land lying significantly lower than that, the country is one of the world’s most at-risk locales if climate change keeps causing sea levels to rise. Scientific estimates predict Tuvalu will become uninhabitable if sea levels rise roughly 20 centimeters, and the current rate of rise means that will probably happen in the next few decades.

Tuvalu’s official unemployment rate is difficult to calculate because much of its economy consists of people growing root crops or fishing for subsistence. But wages are generally low, even for skilled workers.

“The reason I came here was because of the value of money they’re offering us,” says Palota, who has years of experience working as a cashier and doing office work at home and now earns the New Zealand minimum wage of $12 NZ an hour. “At home you can’t get that. Wages for laborers can go up to $2.50 an hour [in Australian dollars], so it’s a big difference. Even comparing the value of money, I thought I should go for it.”

Meanwhile, New Zealand businesses benefit because the country is in the midst of an unusual unemployment crisis; it needs some 40,000 seasonal workers each year and there aren’t nearly enough jobless locals to fill those positions. Horticulture is big business in New Zealand, earning more than $2.3 billion NZ (about $1.85 billion in American currency) in annual exports, and roughly $2.5 billion from food sold domestically.

For its part, the New Zealand government hopes access to a pool of Pacific workers who can return to the same position every year will reduce the tendency of businesses to rely on unspecified numbers of illegal immigrants or transient backpackers. As of April, fewer than 2 percent of growers had applied for RSE certification, but those that have include some of the country’s largest produce producers. In total, about 5000 Pacific Islanders have participated in the first wave of RSE workers.

Palota’s group started out picking and packing apples in the Hawkes Bay region, near Hastings on the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island. Their initial contract there lasted only three months, after which they shifted to Te Puke, near where the Bay of Plenty curves into the northern coast. She now works eight-hour shifts in a kiwifruit pack house, often working graveyard or back-to-back stints.

With its temperate climate and consistent level of rainfall throughout the year, the Bay of Plenty region produces about 80 percent of the country’s signature kiwifruit crop, with about 350,000 tons of the fuzzy fruit exported each year. In the fiscal year that ended in March, the kiwifruit industry made more than $1.16 billion.

An industry that big relies on workers like these Tuvaluans, who will take part in all facets of the kiwi-growing cycle – picking and then packing one year’s crop, pruning the vines to prepare for next year’s, and repacking the stored fruit to ensure export quality – before returning home in early December.

Under RSE rules, employers are responsible for providing “pastoral care” for their workers, though workers pay the cost through deductions from their paycheck. Here in Te Puke, all the Tuvaluan workers live among 350 total workers from the Pacific in a motel-style complex just a short walk from the giant roadside kiwifruit that advertises this region’s specialty. Workers have a large common room with televisions, vending machines and stacks of books, and the facility is about eight kilometers from Te Puke’s small downtown area. The Tuvaluans live four to a room and sleep in bunk beds, with some living in cramped trailer-style rooms in back of the main complex.

Christina Koulapi, 25, also came to Te Puke after working three months in the Hawkes Bay. Originally from the island of Vaitupu in Tuvalu, she speaks eight languages and worked as a preschool teacher for three years back home, but came here for the chance to earn more money picking and packing fruit.

What she’s found, though, is the high cost of living in New Zealand relative to Tuvalu has made it difficult to save the amount she expected.

“I came to New Zealand because the government told us it’s a good way to earn here, but I regret that I came here to the kiwis,” she says. “[The apple orchard] was good for us because we earn more. When we come here, I feel like it’s a waste of time because they’re deducting all our money…

“I used to save money and send money home. Now I just call my parents and say I don’t have enough money to send them. So, I just have to hold it. Instead, I have to ask my big sister in Australia to send them money.”

Workers here under the RSE often arrive in debt, as the employer must pay only half their round-trip airfare from Funafuti via Fiji. On top of that, in Te Puke they pay $105 per week for accommodation, $10 for transport and $10.50 for medical insurance. When there is no work due to poor weather conditions or breaks in the schedule, the workers still pay the same deductions despite the decrease in earnings. And RSE regulations prevent them from taking on additional jobs in New Zealand to earn extra income.

Koulapi worries about being able to save enough to pay off all those expenses and still have anything substantial to bring back months from now. Also, the pollen and particles on the kiwifruit have sometimes exacerbated her asthma. She works through it when she can, because the company here doesn’t provide sick pay if employees can’t work.

“In Tuvalu, you don’t have to worry about tomorrow, you just live,” she says. “Here, most of the time you think of money, money, money. Because if you don’t have money, how do you live? How do you enjoy yourself? In Tuvalu, you don’t care about money. It seems to be like you just go out to the sea and take a fish and tell the owner I’m going to pay you tomorrow. And then the owner will say okay, and it will only cost .50. Things are cheaper. That’s the main thing I noticed. Food here is much more expensive than in Tuvalu. There you can get a tuna, big tuna, for only $1 and here it’s maybe $40 or $50.”

Palota, who is in her forties, also supports family back home. Every week, she sends money back to her two children, aged 12 and 10, who are staying with her younger sister in Funafuti while she works here. Both children wanted to come along but, under RSE rules, workers cannot bring family members with to New Zealand.

She says she’s looking forward to going back to Tuvalu and seeing her family, though she hopes to return to seasonal work next year – at least for the apple-orchard work on the East Coast. But in the long run, she’s hoping to leave Tuvalu and migrate with her family to Australia. Opportunities for her and her children are limited at home, she explains, while Australia offers better wages and a more secure future.

Koulapi, too, says she wants to go back to Tuvalu now but doesn’t see herself living there permanently.

“I plan to migrate, maybe here or maybe Australia,” she says, adding that her sister in Brisbane is looking for ways to help her. “But I’m still thinking of my parents. That’s the main thing. I can’t move away while my parents are living, because I’m the one who takes care of them. I want to go, but I’m stuck. My mom is able to move with me, but my dad doesn’t like it. He wants to stay back in Tuvalu, look after his land.”

So far, her family’s land hasn’t been directly affected by the record tides that have hit Tuvalu in recent years. But when asked if she worries about the future there, she slowly shakes her head.

“I know the government announced that someday Tuvalu may sink,” she says. “I just don’t worry about it now, because I’m still just fighting for a place to stay.”

© 2008 Jeff Fleischer

Jeff Fleischer, a Chicago journalist and author, is examining the fate of Tuvalu, the Pacific atoll that is the world’s most likely nation to be subsumed by water due to climate change.