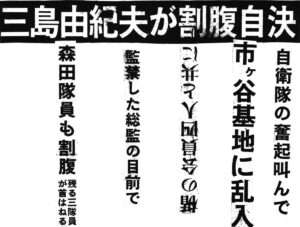

'45 A-Bomb Deaths Unverified by U.S. WASHINGTON (UPl)

A U.S. Defense Department spokesman Friday disclaimed immediate knowledge of a report that 23 American war prisoners were killed in the atom bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.

The Pentagon spokesman said the department's historian would have to make, a detailed search of records before the account could be verified.

In Tokyo, Hiroshi Yanagida, a member of the Japanese Military Police during the war, said 23 of the war prisoners he was in charge with were killed.

He said the Pentagon must have known of their deaths.

– From the Japan Times of July 12, 1970

Prologue

I recently visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki, drawn there by a nagging blend of curiosity and guilt. I wanted to write something, particularly about Hiroshima, but it seemed trite – and somehow obscene to add my belated jottings to that sad chronicle of two murdered cities and at least 260,000 victims of man’s inhumanity to his brothers and sisters.

Unlike the Tralfamadoreans in Vonnegut’s book about the Allied destruction of Dresden, I could not simply shrug and says “So it goes.” I had to ask why. Why Hiroshima? Why Nagasaki? Why two bombs when the atomic blasting of some obscure island near the homeland would have convinced the Japanese that America possessed a new weapon more horrible in its power than all the earthquakes that had ever been recorded?

Shortly before catching the Bullet train south from Tokyo, I had read in the English-language press about 23 Americans – two of them women – who reportedly had been killed by the bomb blast at Hiroshima that sweltering morning of August 6, 1945. For some weeks I had been doing extensive research on the ainoko, the mixed-blood GI “Love Babies” of Japan. I saw a tie-in, as writers are prone to say, between them and Hiroshima that as it turned out was not as tenuous as it would seem at first glimpse. Both are symbols of what happens when two disparate cultures collide; both have had the courage and the will to overcome some pretty steep odds and survive.

Further parallels were obvious: the 23 American POWs had died; the Love Babies took their place, by the thousand fold…. My week in Hiroshima lent itself to analogy, to a kind of therapeutic sentimentality. There is nothing one can say; so if you’re a writer you try to write about it. In the process, one learns a lot about oneself. That, too, is obvious…

My week in Hiroshima (my week, my Hiroshima! –how selfish writers are…) was full of surprises. I hope the following 3,000 or so words you are about to reads or not read, will bear that out.

This report of mine can either be taken as facts as fiction, as fact-fiction or fiction-fact. It can be viewed either as the fellowship newsletter as history, or history as the fellowship newsletter. It can also, I am fully aware, be used to catch the droppings at the bottom of a parakeet cage, or shredded into confetti and showered from a 20th-floor window onto the crew-cut head of some conquering general.

The skeptics might ask, “Did this really happen?” I can only answer by inquiring as to which reality one is interested in…

Personally, I am convinced that some Americans, probably 23 in all, including two women which somehow makes it, to our Western minds, more horrible, did indeed perish at Hiroshima, I don’t know the names of those American men and women. But I would sure like to. I care.

I’m glad I went to Hiroshima. It’s not a nice place to visit – and I wouldn’t want to live there.

So it went.

And, I guess, so it goes as well…

With a Bang and a Whimper

To this days he could not even think about Hiroshima without giggling.

Not that Tao was amused even ironically by what happened there on the morning of August 6, 1945. Or that he Was being subtly’ philosophical, attempting to dilute the unspeakable dregs of horror with the tranquilizing elixir of humor. No, Tao was neither subtle nor philosophical. And he was not a cruel man; only a nervous one.

He was simply, generations later, indulging in a cultural reflex. ln some parts of the world, men laugh until they cry. Tao, likewise, was true to his emotional heritage. He cried until he laughed.

Hiroshima, then, was the cosmic punch line and Tao the coincidental straight man. Flash-boom! A city becomes an atomic rotisserie. Pika-don! More than 260,000 persons are barbecued. Hiroshima! Giggle, snicker, smirk. Reach for a thimble-cup of hot Ozeki saki to silence the choking cough…

…Most of all, it was that damned Korean’s face. For years it had haunted Tao. Over the decades his memory of that flat brown mask had grown sharper, more detailed and clinical. Once, during a rare sexual congress with his tubercular wife, he suddenly remembered that a tiny nick of flesh had been missing from the man’s left ear, probably the memento of some seaport brawl. Another time he recalled the green and silver sparkle of brass teeth, how the morning sunlight burnt through the windshield of the truck, glinting off that shy metallurgical smile. Randomly, he would sometimes become re-aware of the reek of the Korean’s pomade inside the cab. Jasmine pomade, melting on ebon hair in the rising heat…

Unlike so many Hiroshima veterans, Tao was not living in the past. No. The past was living in him – and driving him giddily mad in the process.

“…Please, sir, to stop the truck,” the Korean had said. Tao had pretended not to hear. He stared hard ahead at the mountain road. Tao’s truck was not part of the usual convoy, but was bouncing along alone, the only vehicle moving for miles around, Its cargo consisted of fifty straw mats for the soldiers of the 5th Engineer Battalion Headquarters down in Hiroshima. But Tao had gotten out of combat duty because he was one of the few Japanese around who could drive a lorry and drain a crankcase. He knew his duty. The rumors that the war was already lost might be true, but the sleeping mats he was transporting were, In their own humble way, part of the Total Effort.

Besides, it was fun to tease the middle-aged foreigner who had been assigned as his flunky. After all, he was only a Korean.

“Please, sir, to stop the truck,” the Korean said again. The man squirmed in the seat.

Tao increased the truck’s speed. It had power to spare – and so, at that moment, did he.

“Please, sir…” The Korean was begging now.

Tao glanced over at the agonized face. The war must Indeed be going badly if this was all Headquarters could give him for a helper.

“Why? Why shou1d I stop the truck for you?”

The truck lumbered on for perhaps half a kilometer before the Korean could force himself to reply.

“Because,” he said, writhing now, “I must relieve myself.”

It was the funniest thing Tao had ever heard. He blithely clucked at his back teeth and drove on. Let the Chosen-jin wiggle for a few more minutes…

That, as it turned out, was too long to wait. The Korean clutched at his crotch like a small boy; then his hands gripped the door handle. He was too proud to scream as he leaped, but he did wet his pants. Tao felt only a slight bump as the rear tires passed over the man’s head.

He braked the truck to a stop. But before he could dismount and place the still-warm corpse in the back of the lorry with the sleeping mats (after all, he was only a Korean) the sunlit morning exploded with the light of ten thousand celestial noons. Hiroshima had just been murdered – in broad daylight.

Tao dived under the truck. He lay there a long time, looking almost as dead as the Korean in the road behind him.

It was a long time before Tao, or anybody who had been within sight or sound of the hypocenter of the bombs laughed again.

And when they finally did, it was simply another, more embarrassed way of sobbing. It resembled nothing so much as the sound a small boy makes when he has to go potty and his father tells him to wait until they get to the next gas station…

The next morning was August 7th, but nobody knew or cared any more. It was hot, but not hotter than Hells because Hell is precisely what Hiroshima had become. By noon the temperature had risen to close to 100 degrees Fahrenheit; a very bad day for radioactive abscesses and peeling flesh.

Sergeant Kawamoto of the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, wasn’t thinking about the heat. He had seen the bodies, stacked like so many frozen fish outside Hijiyama Prison, about 1,500 meters from the epicenter of the blast. He had counted them twice, to make sure, and removed their dog tags. Warrant Officer Yamaguchi, his immediate superior, had been very explicit about the dog tags. Two of the frozen fish had been women, Kawamoto had noticed. Through the burned and shredded rags that had been their POW uniforms he had seen their breasts, seared and deflated, like charred pancakes. The nipples looked like baked raisins.

The sight had left the sergeant unmoved. It was only poetic justice, he reasoned, that twenty-three Americans had been killed by their own secret horror-weapon.

It would take Sergeant Kawamoto twenty-five years from that day to learn, and puzzle over, the fact that the identification tags now jangling in his pocket were turned over to the U.S. authorities after the war. Handcuffed to the wrist of a diplomatic courier, they were whisked by special plans to Washington to languish – perhaps for all eternity, perhaps until the Pentagon itself was incinerated by a bomb infinitely more sophisticated than “Little Boy,” the crude firecracker that had pulverized Hiroshima – in an unmarked lead-encased vault. Each dog tag still bore its non-name, its non-serial number, its non-blood type, its non-designation of a nonfaith. Each still was notched by a tiny V designed to fit over the front teeth and hold agape the mouth of its dead owner. Each dog tag was still beautifully functional, and beautifully forgotten. The information each necklace contained, especially the names, was so classified that it transcended anything as mundane as Top Secret. It had achieved the ultimate Orwellian categorization: Unclassifiable.

Nobody, not their brothers or their grandchildren or the President of the United States himself, would ever know who the twenty-three Americans had been. As for the 260,000 others who had perished at Hiroshima, some cindered instantly like the Yankee POWs, others destined to die more slowly and thus more painfully…. Well, they were only Japanese…

Sergeant Kawamoto eventually learned about the dog tags in the Mainichi Shimbun. His old commander, Warrant Officer Yamaguchi, had given an exclusive Interview to Kyodo-Reuter news service on the 25th anniversary of the Hiroshima atom bombing. Like the former Kempeitai himself, the story was tough and to the point. It was told in the first person.

Datelined Nagasaki (where Yamaguchi was now the manager of a successful go-go dance emporium), the article began:

“Twenty-three American prisoners of war were killed by the Hiroshima holocaust a quarter of a century ago. Two of them were women.

“I know this for a fact, I personally gave all of their dog tags to Occupation officers a few weeks later, when the war was over.”

Unfortunately, Yamaguchi could remember only one name on the identification disks, and he was rather vague about that. He thought it was something like Smith.

The Pentagon, prodded by reporters, replied evasively that its historians would check into the matter, and let it die at that….

…But Yamaguchi was no fool. lie hadn’t risen to the rank of warrant officer in the dreaded Kempeitai and been placed in charge of three prison camps in Hiroshima without learning something. Ironically, the American fliers who had been shot down in the prefectures and placed in his dungeons had been his best teachers. Never, he had learned, tell anybody everything you know.

Perversely, Yamaguchi had kept the best part of his story to himself. It would hold for another day, when the reporters’ fee would be higher. Maybe even until the thirty-fifth anniversary of Hiroshima….

“Mama. Mama,” said the American, “Mama, where are you?”

Then the child’s voice turned official and brisk. It became the cocksure baritone of a teenage lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

“Yes, I’m sure of it, sir! It’s our new death ray. I’m sure of it!”

Warrant Officer Yamaguchi was baby-sitting a walking, corpse. One of Sergeant Kawamoto’s frozen fish had stirred to life while Yamaguchi was photographing the bodies. It had actually staggered to its feet and was stumbling along the street toward Tenjim-machi in the center of what only yesterday had been Hiroshima.

The American’s clothes had been torn off by the concussion of the bomb blast. He was naked except for the olive-drab drawstring of his GI under wear. The straw pads thonged to his feet were far too small; it looked as if he had slipped into a child’s sandals by mistake.

The flier was nineteen years old. He was choking on his own blood. Like most strangling men, he had an erection.

“Mama, mama,” he said. “Don’t get mad at me, mama. I’m afraid I’ve scalded myself….”

Yamaguchi could understand no English then. But he knew the man was moving by death reflex, the same kind of muscular spasm that allows a chicken with its head cut off to strut a few final hops before its body gets the message that it is already dead.

The American never saw them, the burned ones. Traumatized and their skin peeling three layers deep from chronic atomic sunburns they were staggering toward the Red Cross Hospital. Some had urinated on their ulcerated arms and legs in an attempt to alleviate the pain. But that had only made it worse.

“Eraiyo, Eraiyo! It hurts. I can’t stand it,” the women among them cried. They had drifted back from the hills near where Truck Driver Tao had run over his Korean helper. Only inhuman pain could have forced them to return to the hell-center of the pika-don bomb.

Yamaguchi felt a wave of compassion for the dying American. Maybe, just maybe, he could pull him off the street into a doorway or crevice.

It was too late. The burned ones had seen him, the Blue Eyes With the Brown Hair.

The first rock hit the American in the mouth. He felt tentatively at his broken teeth, like a timid schoolboy reacting to his first punch in a playground fight. He crumpled, gracelessly, to the ground. He was doubly dead now, but the pack didn’t stop tearing and beating until the pain of their own wounds became unbearable.

Warrant Officer Yamaguchi could only watch as they picked up the American’s broken body and carried it to the banks of the River Ota. There they nailed the remains of the young flier so that his lifeless blue eyes could stare out at the bloating rubble of Hiroshima city.

With unintentional irony they had crucified him on the blackened branches of a cherry tree. They could not have known, or cared, that the Japanese cherry was the favorite tree of Harry S.Truman, the American President who had given the order to scourge Hiroshima. He was almost as fond of the Japanese cherry blossoms in Washington as he was of the song “Home on the Range.”

Yamaguchi,\, a man with too soft a heart to ever be a real success in the Kampeitai, looked away. He felt an embarrassment, a sadness.

Making sure that none of the burned ones saw him, he hung his head – and giggled.

Epilogue

Civilian Truck Driver Tao and Kempeitai Warrant Officer Yamaguchi have never met. It is doubtful if they would like each other very much, or find a great deal to talk about if they ever did. After all, Hiroshima is such an ancient saga. It happened so long ago that twenty-five percent of the Japanese school children, polled by their teachers across the nations did not know which country had exploded atomic bombs on two of their major cities. Less than half of them were sure exactly what an atomic bomb is, or was. Their ignorance, though, is not only forgivable; it is just, They are techno-tots, children of the Doomsday Age. Kids who may one day soar to the moon are only bored by Greeks who try to fly by gluing phony wings to their shoulders and leaping off of cliffs.

About the only bond the two old veterans would have, besides their undimming memories of Hiroshima, is an affection for the Yomiuri Giants baseball team and a distrust of anyone who is not Japanese.

But they do have one other thing In commons although neither would admit it, especially to a stranger. Both are illegitimate grandfathers. Their grandchildren, one a boy and the other a girl, one half-black and the other half-white, are ainoko. The word connotes no ancestral pride or filial warmth. It is a distasteful words a cultural graffito scrawled across the national conscience.

Ainoko is really a synonym for hate. It means Love Baby.

The mixed-blood GI grandchildren of Tao and Yamaguohi, in an oddly poetic way, are very much like the ghosts of Hiroshima that still haunt the two reluctant patriarchs.

You can shut your eyes and giggle all you want. But the Love Babies, the sparrows of the nowhere night, will not go away…

– the end –

Received in New York on October 21, 1970.

©1970 Darrell Houston

Darrell Houston is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. This article may be published with credit to Darrell Houston, the Post-Intelligencer, and the Alicia Patterson Fund.