Normally, Estefani Nuñez parks the small yellow school bus she drives each day by the side of her home in the Rosedale neighborhood in Queens. On the day before she knows it’s going to rain, she parks her school bus a block away. When it does rain, she puts on her tall black boots to wade through water to make sure the children she has to pick up get to school on time.

Sometimes the boots aren’t enough and she is forced instead to wear garbage bags over them. Once in a while, when the water is too much, her own two kids become trapped at home because the flooding prevents them from leaving their house to make it to class.

The school bus driver lives on a block that runs perpendicular to Brookville Boulevard, at the dead end of her street; her home overlooks a marsh. From her front step, she can see fields of grass and a small body of water. Depending on the height of the tide, the water can swell and enter her property, soaking her yard and submerging her basement. On a day when both the tides are high and it’s rainy, flooding from both swamps her entire block.

Historic disinvestment in Black and Brown neighborhoods across the city has now left homeowners at the mercy of flooding that has been intensified by the climate crisis. Residents have pushed for solutions for decades, but many believe their concerns are ignored.

“It’s a double-whammy,” Nuñez said about the effect of high tides and intense rainfall on her street.

Brookville Boulevard, or Snake Road as locals call it, has always been prone to high water. News outlets have long documented the threats of flooding in the neighborhood, as well as fatal car crashes that have occurred on the road, which has little protection, such as guardrails and shoulders, to protect drivers from skidding into the marsh. In 2019, the MTA rerouted the Q114 bus due to the flooding and constant road closures, but now neighbors fear that an already dangerous road will become even more unsafe as the city gets wetter due to climate change.

Sea level rise will exacerbate high tides, putting New York City on the path to get more tidal flooding due to climate change. By the 2040s, the city is expected to see 60–85 days of tidal floods, according to the New York State Climate Impacts Assessment.

As the tides rise, low-lying neighborhoods in southeast Queens, the Rockaways, and others near Jamaica Bay, some of which are at sea level, are at risk of even more flooding. Nuñez described the flooding on her block as an ocean.

Not only will the city see more chronic tidal flooding, more extreme rainfall may affect neighborhoods like Rosedale where Nuñez lives. In 2021, heavy rain from Hurricane Ida killed more than a dozen New Yorkers, mostly in Queens. By the end of the century, New York City could see up to nearly a third more rainfall each year. If Nuñez remains in Rosedale, there are likely to be more days that her kids will be stuck at home because of the flooding on her block.

City officials acknowledge that if nothing is done, flooding on Snake Road will only worsen. Now, $3 million in federal money is paying for a feasibility study of a nearly one-mile section of the roadway that runs in the middle of wetlands. The Brookville Boulevard Flood Mitigation Study will look at alternatives to relieve flooding, including raising the road and placing signs and warning devices along the route. The study is expected to launch this year and will take nearly three years to complete. And while city officials refer to the study as imperative and game-changing, residents have been waiting for years for solutions to make the boulevard safer.

Shifting tides

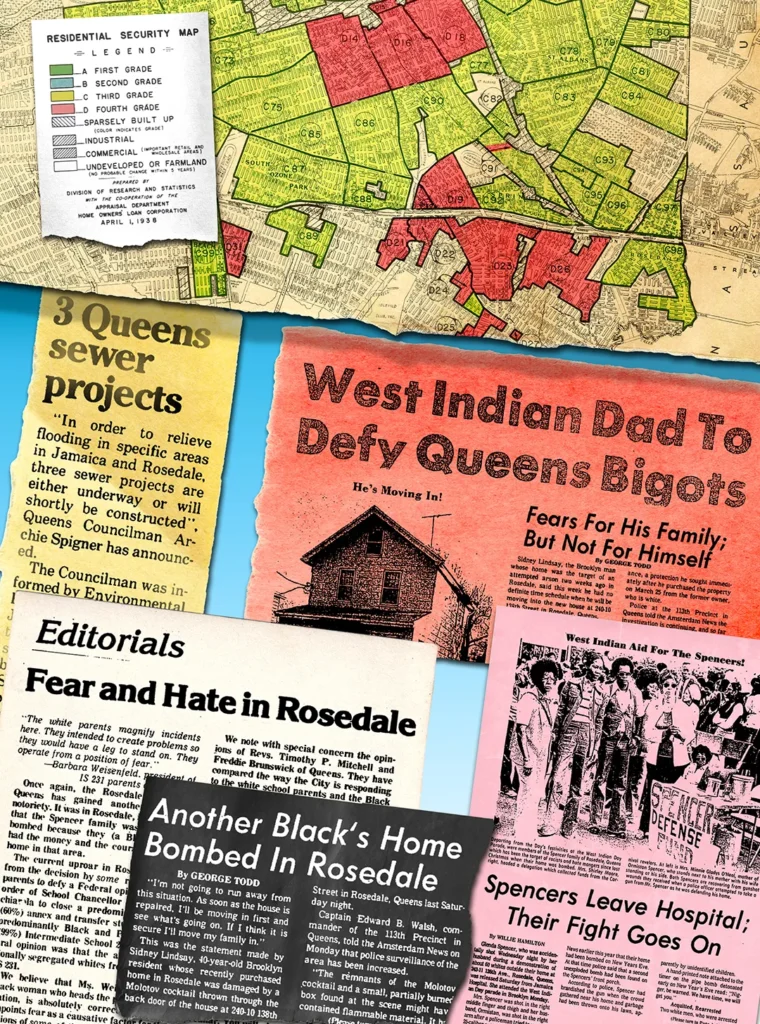

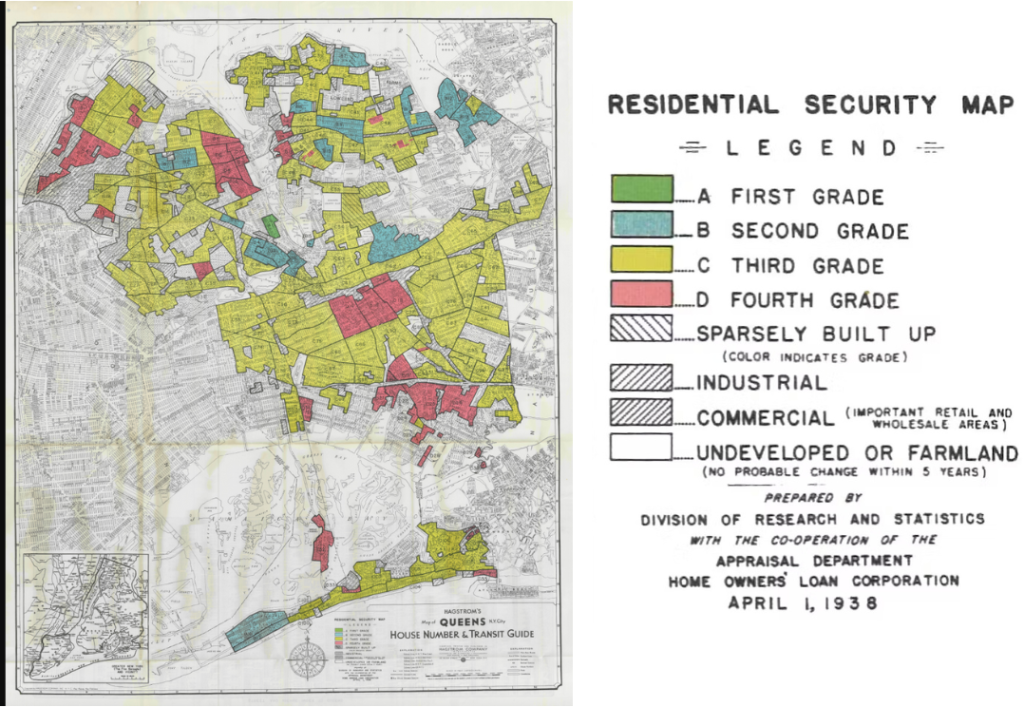

Rosedale was originally built on swampland and has been prone to flooding for much of its history. Redlined maps from the 1930s outlined not only the racial composition of the area, which was mostly white at the time, but also environmental threats. For Rosedale and surrounding areas, that meant being a low-lying area as well as a lack of sewers.

In the 1970s, Black New Yorkers who started moving into the neighborhood were met with violence. In 1974, the home of immigrants from Trinidad was pipe-bombed, and some white residents formed the group Returning Our American Rights (ROAR) to prevent Black people from buying houses. A federal lawsuit was filed against ROAR and ultimately one of the leaders of the group was accused of bombing the home.

Today, Rosedale is predominantly Black and Brown, and systemic disinvestment means that this part of the city is playing catchup when it comes to large-scale infrastructure fixes. It’s one of many areas that are now on the frontline of the climate crisis.

Crystal Brown has lived in neighboring Brookville since 1987. She moved there from Rochdale Village, a cooperative built in the 1960s as an experiment in integrated housing. Although she describes Rochdale as a beautiful community, she wanted to own a home.

She travels on Snake Road a few times a month to go to the beach in the summers in the Rockaways or to go shopping. It’s also a shortcut to get to some parts of Nassau County. She’s always been concerned about the safety of the road and said her worries have only increased with climate change.

“God forbid there should be any kind of evacuation from Rockaway,” she said. “It would be a nightmare.”

The Rockaway peninsula is designated “red” on the city’s evacuation zone map, which means if a mandatory evacuation is issued during a dangerous storm, people in that zone will be ordered to leave first.

State Senator James Sanders Jr., who represents the area, expressed concern about another storm like Sandy hitting the peninsula. In a 2022 letter of support for the city’s application to fund the Brookville Boulevard study, Sanders wrote, “elevating and repairing this road would mean that the Rockaway residents would be prepared for the next major storm event and would be able to evacuate in an efficient manner, if needed.”

Local resident Guy Lalanne said using Snake Road can cut down his commute by 15 minutes—an essential block of time during an emergency. Originally from Haiti, Lalanne moved to nearby Springfield Gardens in the early 1990s. He recalls the day he closed on the house he bought with his mom and two siblings because there was a rainstorm—but there wasn’t any flooding and he wasn’t informed that downpours would be a persistent problem.

Shortly after he moved in, heavy rainfall caused flooding in front of his home, which is on a hilly block. “It was like a river,” he remembered about the day. “I wish I had a kayak.” He said poor drainage systems and catch basins filled with leaves exacerbated the problem.

Like his neighbor Nuñez, Lalanne needed garbage bags to walk to his vehicle for a time. His home is also near the marshland and he gets both tidal and flash flooding. “The study is the best excuse,” he said about previous proposals to study the area that haven’t come to fruition.

In 2013, former Governor Andrew Cuomo announced plans to fund repairs post-Sandy and build resiliency projects under the NY Rising program. The $750 million initiative was supposed to identify New Yorkers’ most urgent needs.

However, even when he was in office, many of those plans didn’t come to fruition, including a proposed study to raise Brookville Boulevard.

Around the city, flood mitigation plans are in the works, from protecting NYCHA residents to building flood barriers along the Lower East Side to sea walls and surge gates in the Rockaways and Jamaica Bay.

Brookville Boulevard in Queens and Staten Island’s Travis Avenue share many things in common, including flash flooding. The water on both roads gets so bad that they become impassable. Both are also surrounded by wetlands. In the case of Snake Road, the surrounding wetlands are governed by state, federal, and local government, which, according to local politicians, makes it easy to pass the buck about who is responsible for fixing the road. Travis Avenue, however, shows that there is a precedent in the city for raising roads affected by flooding. The Travis Avenue Elevation Project will raise a nearly 1,000-foot section of the road.

In 2018, the project received funding to begin the following year, but it is years behind schedule and not set to be completed until next year. The program was part of the city’s Raised Shorelines initiative under the de Blasio administration.

Other proposed projects under the initiative included crown walls in Old Howard Beach and stormwater management in Mott Basin. Howard Beach is another area in Queens, on Jamaica Bay, prone to both flooding from the tides as well as rainfall.

A sinking liability

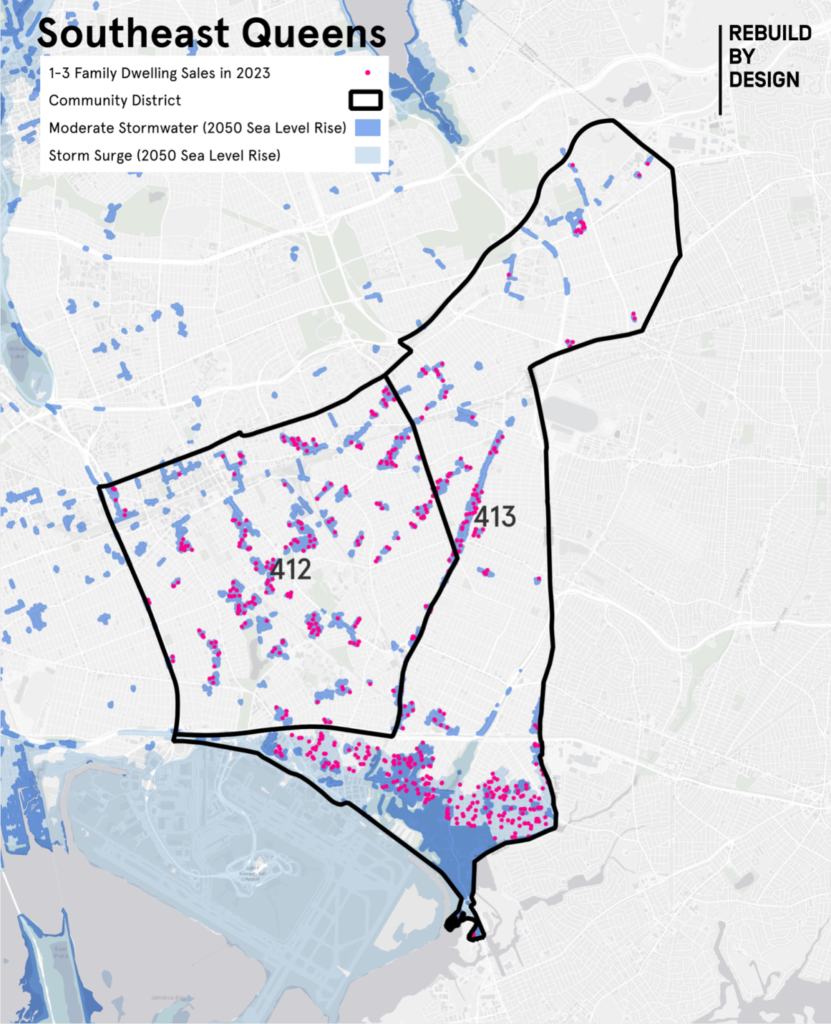

Nuñez’s husband worked two full-time jobs to save up for the house she bought six years ago. Her family is just one of many newer arrivals in the area. Amy Chester, director of Rebuild By Design, said solutions to the climate crisis have to be balanced with the city’s need for housing. Last year, more than 2,500 one- to three-family homes in Queens were purchased in or near flood risk areas, according to a data analysis by her organization.

Mayor Eric Adams has proposed the “City of Yes” rezoning plan, which would add more housing across the city in the years to come. Rebuild By Design used 2023 data to reveal that about 20% of sales of one- to three-family homes in Queens happened in floodplains.

According to the organization, last year more than 160 homes sold in ZIP code 11422, where Nuñez lives, are at high risk of coastal and stormwater flooding. That means Nuñez and her neighbors may end up pouring their money into homes that will inevitably flood.

A road to safety

Possible options to keep New Yorkers safe include buyout programs. “There are communities in New York City that already are asking for buyouts and have [been] since Hurricane Sandy,” said Chester. “That’s definitely a solution in the areas that we aren’t able to protect.” Her organization is working with the state on what a buyout program could look like in Northern Queens, another section of the city fatally affected by Hurricane Ida. She said it’s key that a program offer options for residents to stay in New York City or nearby. Shortly after Hurricane Ida, some residents in Southeast called for a buyout program.

While some New Yorkers are open to buyouts, others aren’t. “I think it’s a terrible idea,” said Lalanne. He’d rather see flooding fixes made so residents can stay in their homes. Furthermore, buyout programs can be limited in scope, reactive to particular disasters, and can either miss those most in need of the programs or stoke fear of gentrification.

Chester is also worried about measures already on the books to keep New Yorkers safe, including New York State’s flood disclosure law, which went into effect earlier this year and requires sellers to alert buyers of a home about flood risk. That includes whether the home is in a hazard zone or if there’s been damage from past flooding. Before the laws, sellers could pay a $500 fee to opt out of disclosing a home’s flooding history.

However, she said the new law doesn’t go far enough. It mandates that flood history be disclosed at the time of sale, not when the home is advertised. “When you actually read the legislation, you realize that it was very specifically drafted to make the real estate industry happy,” Chester said.

Lalanne said flooding has subsided in recent years where he lives. “To their credit,” he said about the city, “they’ve spent a lot of money in the area.”

© 2024 Roxanne Scott

Roxanne Scott’s research was supported by an Alicia Patterson Foundation grant. This article appeared in the August 22, 2024 edition of Amsterdam News.