March 25, 1971

Scotland has problems of housing, unemployment and religious bitterness which make it a society torn by class and racial tensions…and the difference between social classes within the same nation may be as great as the differences which divide nations. An anglicized Scot of the upper class is much closer to his English counterpart than to a worker in the Gorbals, and the social composition of the regions and cities of Scotland marks each off from the other as effectively as it marks Scotland off from England.

(Modern Scotland, by James Kellas)

Some students of nationalism, after adding up the ways that institutions support the concept of a single Scottish nation, and subtracting the sorts of divisions Kellas lists, add a further factor they call “myth”.

Kellas says, “There is a Scottish Dream, or Scottish Myth, and it is a part of Scottish national consciousness (or unconsciousness?).”

That packs a lot into one sentence, but he clarifies in a footnote what he means by “myth” – “a self-image whose truth or falsehood has never been established.” Myths, then, are not mere fictions or parables left over from extinct religions, but may also be beliefs about what a dispassionate observer might consider to be debatable matters.

There is, for instance, the myth that Scotland is what a speaker at the Scottish National Party conference last October called “a leader over the ages in the struggle for freedom.” In support, nationalists like to go all the way back to William Wallace, a leader of the 14th century Wars of Independence against England, and to the Declaration of Arbroath which was issued during those wars, in 1320. One sentence that the SNP quotes in its “Declaration of Nationhood” has a familiar and stirring ring:

“We fight not for glory or wealth or honors, but only…for Freedom, which no honest man surrenders but with his life.”

The theme of struggling for freedom, both national and individual, also runs through a number of subsidiary myths which link the ideal to Scottish institutions.

Take the Church of Scotland. It can be seen as the result of Scotland’s battle against both Rome and England. Nationalists pay more attention to it than might be expected because the Church Assembly is the nearest thing in Scotland to a national representative assembly and it sometimes takes stands on political issues. The Reformation was also a struggle against the absolutist and hierarchical Catholic and Anglican churches; Scottish ministers became mere ministers while all members of the church were given equal say in its governance.

The move toward equality and freedom from control by an elite led to an effort to provide education for all. Scotland began to establish true public schools in the 16th century. The Presbyterian Church set itself a goal of a school in every parish, open to everyone, with no fees for the poor, and with advancement strictly according to talent. England is still debating whether to continue an elitist division of schooling., but more than 300 years ago Scotland created a system in which poor but bright boys would be helped to go all the way to the university and beyond.

The stream did not peter out then. Scots have led in the fights for economic freedom. Robert Owen, though Welsh himself, initiated the cooperative movement at his father-in-law’s mills at New Lanark., Scotland. Keir Hardie was only one of the Scottish leaders of the early Labor Party.

Now, this sort of thing is easy to criticize. References to the past can be pushed to absurdity. H.J. Hanham. quotes a letter-to-the-editor from a Scottish Earl who claimed that the ancient clans practiced “pure democracy.” And less exaggerated claims can still go too far.

It could be said, for example, that the Declaration of Arbroath was drafted by nobles and knights little different from those in England who obtained the Magna Carta, except that they fought a foreign king instead of their own. For most of them, “freedom” was not for the populace at large but only for the nobility, whose power over the rest was to remain unfettered.

Again, the clergy did lose power in the Reformation, but not to the whole congregation. Small groups of elders were largely in control, and their control was sometimes stricter than before because the clergy were no longer even nominally independent of secular powers. Moreover, the Kirk, and kirks after the 19th century splits, sometimes became moralistically narrow and imposed a drab intolerance that was the very opposite of freedom for individuals. (It is said that there are still places in Scotland where Sabbath strictness bans so much as a Sunday afternoon stroll.)

The schools were not in fact established in every parish, and in any case one school could rarely hold All the children of even a small parish.

In practice, the dumb laird’s son was far more likely than the bright crofter’s son to reach the university. Poor boys, dumb or bright, usually got about four years’ schooling, and girls of any sort got less. The widespread literacy that so startled l8th century travelers was real, but it was often the ability to read but not to write. Today, Scottish schools are often cited as horrible examples of authoritarian schools with an emphasis on rote learning that stifles curiosity and debate.

Robert Owen was a great propagandist and, for his time, an enlightened employer, but he seems to have made little effort to try cooperativeness in his own mills. Keir Hardie could not get elected in Scotland and had to go to Wales to win a seat in Parliament.

Nevertheless, the myths should not be dismissed out of hand. If they are not quite true, they are not wholly false. They are less important as history than as parables, and more effective as parables because they appear as history. They pick out certain developments and trends, and say, “These are Scotland’s characteristics and ideals and these are the goals that Scots should strive for.”

The ideals tend to be anti-establishment – for the individual against government, for small nations against large ones, and in general for the underdog. Related as they are to continuing Scottish institutions, the myths are easily turned to current uses, and the number of times England appears as the villain of the piece makes them attractive to nationalists.

Does Britain still send comparatively few young men and women to college? Scotland would not lag so if it had been free to expand the educational base it had built before the Union. Is Britain wracked by labor strife and scarred by poverty? Scotland would not be if its more open and more technically-oriented education and its efforts toward community cooperativeness had not been overwhelmed by England. Is England still class-ridden? Scotland would not be if its individualist and democratic tendencies had been allowed to come to fruition.

It is easy to see the over-simplifications in other people’s myths. It is also true that the uses of the myths can be pretty far-fetched. For example, the SNF’s Declaration of Nationhood says, “Let it not be forgotten that Scotland is…a kingdom…The Scottish Crown is recognised in fact and in name with duties and prerogatives differing substantially from the Crown of England.” Leaving aside knotty constitutional issues and the question of how substantial either monarchy is today, it may be doubted that many nationalists would have much interest in restoring the monarchy of 1707.

Nevertheless, the fact is that a great many people say that the myths are finding a new audience or having a new impact in Scotland today.

Part of the reason is usually said to be that Scotland is undergoing stresses that arouse dissatisfaction that focuses on the nation’s allegedly subservient place.

A second reason has been offered by an extraordinary range of people. That is: “British myths are dying,” It has been said in nearly identical words by a Welsh nationalist, a Welsh Labor Party official, a Scottish nationalist, and a Scottish Liberal MP, and written in books, a Scottish newspaper article on nationalism and an English newspaper article about labor relations.

There are of course all sorts of myths in Britain. Some are essentially English myths that downgrade the accomplishments of Scots and Welsh before they were fortunate enough to unite with the Eng1ish, ‘There is, for example, the myth that Scotland was a wild wasteland where clansmen went to war for the fun of it and especially enjoyed raiding innocent Englishmen in the northern counties, where massacres like that at Glencoe were annual events, and where the king’s authority rarely extended beyond the end of his sword.

In fact, at least until the Tudors, England’s government was very like Scotland’s in form and power, and English history is not notably less bloody than Scottish. The Borders were for long an area rather like Kansas in the 1850’s, and people from both sides happily raided on both sides. Glencoe was so shocking because it was uncommon, and while it was the culmination of a feud between Campbells and MacDonalds, it was also at least connived at and perhaps ordered by King William’s government to put down a troublesome chief.

(There is also a myth that the English teach history magnificently, My impression – reinforced by some of what passes for history in the BBC opus, “Elizabeth R” – is that history at the level of “1066 and All That” is as common here as history on a “1776 and All That” level in the United States.)

Those myths may or may not be dying, but since they probably never had great influence in Scotland anyway, the ones of interest here concern British greatness and the desirability of being a Briton.

British history being better known than Scottish, slogans or catch-phrases should be sufficiently evocative. England had the first industrial revolution and was the workshop of the world. England ruled the waves and had an empire on which the sun never set. England has not been successfully invaded since 1066 and stood alone in 1940. England has a long tradition of non-violence based on a love of freedom with order that created the Mother of Parliaments. The English may know their place, but, they also know and get their rights. English rulers have somehow always managed to muddle through to compromises that gave power to rising classes and staved off revolution. A relatively young myth that may be short-lived is that the English do not carry materialism to extremes and, by avoiding the rat race, lead more civilized lives than., say, Americans do.

Never mind how much of this can be picked to pieces. The point is that it has been easy to select events and to interpret them in such a way as to make a case for pride in being British and for believing that Scotland and Wales had benefited by being so.

It is not so easy now. Britain is absolutely stronger and wealthier than ever before, but relatively it has declined. It is puny beside the superpowers, and is “wealth” the right word for an economy that will soon, according to reports on present trends, produce the lowest per capita income of any nation in western Europe except Portugal?

Indeed, a kind of counter-myth is growing up. Thus: with the empire gone forever, Britain is just a small nation with a weak economy. Britain could be kicked around with impunity over Suez and is laughed at by Rhodesia. The gnomes of Zurich, or somebody, keep undermining the pound. Britons keep inventing things, but the capital and the far-sighted managements needed to produce them are lacking. The world-wide wave of violence is subverting even British peaceability, as shown by bombings or the threat by residents of Cublington to use force to prevent construction of an airport there. Parliament is incapable of dealing with modern problems. Worse yet, Parliament may soon pass out of British control – or so some opponents of entering the Common Market declare. At a rally in Glasgow, anti-marketeers displayed a column 15 feet high – the height of legislation Parliament would have to pass “without debate” to bring British statutes into line with Europe’s. Alternatively, the French may veto Britain’s application again and the economy will decline further.

No doubt the symbol of Britain’s current state is the bankruptcy of Rolls Royce. Rolls is not just any company. What it is may be hard to articulate, but that it is special was clear from the tone of blank incomprehension when people said. “Rolls Royce has folded.”

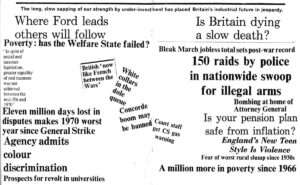

When Rolls Razor crashed some years ago people could blame it on fly-by-night operation or, with a different bias, on the machinations of big capitalists – at any rate, they could fit it into a familiar pattern. But what does one say when Rolls Royce crashes? That the whole economy is on the verge of collapse. Certainly a kind of case can be made by citing the fall of “RR” and other companies, rapid inflation, unemployment at a post-war record and rising, low investment, low productivity, and the disruptive effects of frequent strikes.

There is another side to economic myths. That is that Britain uses its wealth, however limited it may be, in a particularly civilized fashion. To use Galbraith’s distinction, which is very popular here: the quality of private life can be higher in the U.S., but the quality of public life is higher in Britain.

Now this myth is threatened. Urban sprawl is an old enemy, but now the quality of central cities, of the countryside, of public transport., faces an onslaught by hordes of automobiles and a program of highway construction that seems to be making most of the familiar mistakes.

Also threatened is a quality that might be called humanness. It has often been said that Britain has pretty well eradicated poverty, or at least its worst effects, through the National Health, extensive unemployment compensation, benefits for children, orphans, widows, the aged and the crippled, and all the rest of the Welfare State – mostly without degrading means tests, and all supported by an income tax that not only provides the money but is so steeply progressive it keeps the gap between rich and poor from widening.

New or increased charges for previously free services, or the imposition of some means tests, may cast doubt on the Welfare State myth, especially under a Labor government. Under a Conservative one they tend more to confirm prevailing political ideologies. But large holes are appearing in other parts of the myth.

Numerous books and articles have presented evidence that both the number and the proportion of people in poverty has increased substantially in the last ten years, that a major part of the increase is among families headed by fully-employed males, and that the rate of increase has been accelerating. There has also been a spate of publications with evidence that the distribution of incomes has not changed greatly in the last 30 years, that the concentration of wealth remains high by comparison with other industrial countries, and that the gap between top and bottom incomes has increased absolutely and proportionally in the last five years or so. Peter Townshend concluded in an article in The Times on March 9: “The British tax system overall is very unprogressive,” and “wealth is distributed more unequally in Britain than in most other industrial countries.”

The studies also indicate that previous estimates of numbers in poverty were under-stated and previous estimates of the redistributive effect of income tax were, as in the United States, greatly overstated. Thus, the actual change between then and now may be quite small. But several commentaries I have seen are clearly outraged by the considerably larger gap between what was believed and what is believed now.

James Reston suggested in a recent column that the British, for all their griping and gift for finding the leaden lining in every cloud, are still a people who buckle down without heroics and do the job somehow.

Maybe so, but what is the job to be done? It is one thing to stand up to the Nazis or to tighten belts to preserve the nation’s ability to trade. But how is a general crumbling to be combated? What is the remedy when reduced auto production is a threat to the economy and increased auto production is a threat to the environment? Does increasing political violence mean that some dangerous people must be repressed, or that something basic is so dangerously rotten that the tradition of nonviolence is eroding?

I was impressed almost from the moment of arrival in England by signs of low morale. Gloominess and anticipation of doom characterized discussions of Britain’s troubles. It is still true that good news is no news, but the media displayed a remarkable facility for finding indications that bad as things were, the worst was still to come. Typically, when the balance of payments accounts showed an unprecedented surplus for 1970, nearly every commentator managed to predict a poor showing for 1971, or to show that devaluation was likely to be necessary again soon, or both.

The general pessimism was so much stronger than my own, admittedly far from expert, reading of the news seemed to warrant, that I began asking about it. The sample is awfully small – half a dozen politicians, a few journalists and I, and only one economist – but the results were instructive. All of them said, in effect, “It’s true that things are not quite as bad as they are being portrayed, but…” – and then the sad litany was read off again.

Awareness of problems sets people looking for changes to make, and no doubt most Britons would rise to a challenge if they knew what the challenge was. One possibility was indicated in February by a poll that found most people willing to enter the Common Market or to stay out if they believed ‘that either course would improve prospects, not for them, but for their children. Then they would be prepared to undergo another period of belt-tightening.

For the moment., however, the change that seems promising to the single largest group of people is simply to get out. According to a (Gallup Poll published March 22, no fewer than 41% of British adults would “like to go and settle in another country.”

Now, similar feelings may be found all over Britain. (Or the world. The Gallup Poll found that 27% of ‘West Germans, 18% of Swedes and 16% of the Dutch would like to emigrate. So would 12% of Americans, twice as many as in 1959. And it would be hard to find a country without other signs of discontent.)

But the feelings are not expressed in just the same way everywhere. The English can think of leaving Britain as individuals. The Scots and Welsh can think of leaving Britain and taking their countries with them.

When Britain seemed generally successful and the problems of the day could be expected to be mitigated by growing wealth and power, the advantages of the connection with England cancelled out the effects of national distinctions. When successes are rarer and when problems are expected to get worse, the value of union is questionable and separatist tendencies are reinforced.

Nationalists like to complain that the English say “England” and “Britain” interchangeably when things are going well, but only “Britain” when they are not. It is not unnatural that the Scots and the Welsh emphasize the Britishness of successes, but the Englishness of failures.

People may be quick to pass the buck when they can, but they are a lot slower to make really major changes. Troubles predispose them to look for changes, but the first step is to tinker with what exists, not to start a revolution. To make a revolution – which is, after all, what the nationalists propose – is to leap into the unknowable. And that requires a belief that conditions are unbearable and cannot be put right by reform, and faith in a program that is necessarily hard to have faith in because it not only does not arise out of traditions and current trends but proposes to do away with much that is familiar.

So the nationalists must build a case that is highly pessimistic about the present and highly optimistic about the future they intend to create. (One result is that bad news is reported in a tone common to many reformers and all revolutionaries. It is not exactly relish, for they are often sensitive and altruistic, but it is far from downcast, since the worse the situation the greater their opportunity.) Parts of the case appear below.

Bad as England’s economic situation is, Scotland’s is worse. England’s per capita income is low compared with other industrial nations, but Scotland’s has averaged about 15% lower for the last ten years while the cost of living is almost as high. The unemployment rate for all of Great Britain is now over three per cent. In Scotland, it fell below three per cent for only one of the last 12 years. The Scottish rate has consistently been one and a half to two times the British average and is now 5.7%. (The current Welsh rate is not quite as spectacular – 4.6% – but it too is as usual more than one and a half times the British rate.)

It makes no difference which party is in power. Prices are rising now, but they rose under Labor. Unemployment was almost as high when Labor left office in 1970 as when it came to office in 1964. The Tories are raising health charges, but labor first imposed them. Labor did not close the gap between Scottish and English incomes, and let the gap between the highest and lowest personal incomes increase.

By the way, the figures on incomes are surprising to all parties (whatever else may be expected of parties of the left, they are expected to be levelers), and bitter to Labor’s supporters. The impact is great in Scotland and Wales for they are Labor strongholds. Conservatives have not won a majority in either country for forty years. In 1970, Conservatives won 23 of the 71 Parliamentary seats in Scotland and seven of 36 in Wales.

No difference is seen in foreign policy either. Tories come right out and support the U.S. in Vietnam, and Labor refused to condemn forthrightly. The Labor government helped crush another small nation struggling for independence by backing Nigeria against Biafra, just as the Conservatives would have done. Both parties support colonialism – not just in Africa or Asia, but also in Scotland and Wales where industrial materials and talented men are creamed off to England while modern industry remains underdeveloped.

The colonialist argument is emphasized somewhat more strongly in Wales. That may be because Wales was conquered and Scotland was not. It also appears that Plaid Cymru is generally to the left of Labor, while the SNP tries to be between Labor and the Conservatives. One reason for that difference is that the Conservatives are stronger in Scotland than in Wales: In both 1966 and 1970, they took about 38% of the general election vote in Scotland but only about 28% in Wales.

On the other hand, Plaid Cymru no longer makes the “robbery” argument – that Wales pays more in taxes than central government expenditure returns – but the SNP does. Few economists who are not nationalists seem to accept even the contention that either country pays its own way, but the uproar in Scotland grew so great that in October 1969 the Treasury issued a reply contending that revenue from Scotland is considerably below expenditure there. That only added fuel to the fire, since both sides must make large assumptions because many essential statistics are not collected separately for Scotland.

Labor and Tory also agree on going into the Common Market, on excluding Scottish and Welsh representatives from negotiations, and on ignoring the potentially disastrous consequences for farming and fishing and industrial development in Scotland and ‘Wales. Scotland has little effect on the bureaucrats in London. It will have none on those in Brussels.

But what if Scotland were independent? Here the nationalists face some difficulty, for they have no recent Scottish experience to point to. The lack is met in two ways. First, they point to the myth-history of what Scotland was and what it showed signs of becoming at the time of the Union. Scotland had the greater universities, was the more democratic, and so on.

Second., they point to other small countries which are successful, and especially the Scandinavians. I will return to this point below, but it may be seen in action along with the others that have mentioned in the following resume of the speech SNP Chairman William Wolfe gave at the party conference:

“The past is the key to our future. We are essentially an ultra-democratic people” for whom the sentiments of the Declaration of Arbroath still live.

“Scotland’s talent for unorthodox and radical thinking” was revealed in the Reformation and in the writings of Adam Smith, David Hume and others. “Scots have been in the forefront of innovation in science, engineering…and other fields. Scots like Keir Hardie…were in the forefront of the radical labor movement when it was a genuine movement for social justice.”

“Given the chance, Scots and Scotland could continue to give much to the world.”

“Had the whole nation been bound together with a common aim, what would we not have achieved in the 20th century, had we had self government 60 years ago?”

“Instead of stagnating…held down by London’s imperial paternalism and pretensions, we Scots might have achieved the economic growth of Finland or Norway, the cultural vigor of Denmark, the conquest of poverty that we see in Sweden. Instead of being tarnished with the image of the ‘sick man of Europe’, instead of having to share British foreign policies, such as the two-faced policies on the Mid-East, gunboat diplomacy in Anguilla, and the genocide in Biafra.” Scotland could be more prosperous, take better care of “children and sick and old people, and have a fairer distribution of wealth.”

An independent Scotland could work “for world cooperation and peace, side by side with the Scandinavian democracies and other small nations of the world which I believe, have the most distinctive contribution of all to make to the progress of humanity.”

References to Scandinavia also come up frequently in discussions of the high emigration nationalists consider to be the curse of Scotland and Wales. For example, Gwynfor Evans, the leader of Plaid Cymru, said that Denmark has a higher standard of living than Britain) and has surpassed Britain in some of the prerequisites for further economic growth – investment in transportation and modernized production plants, higher education generally and technical education in particular, and so on. Denmark, he said, though smaller and poorer in natural resources than Wales, is both independent and “able to provide for its people.”

I said that while I did not have statistics I thought that emigration from Scandinavia was generally fairly high. He did not know the figures either, but disagreed that emigration from Denmark would be comparable to that from Wales. At that point, communications broke down. To my mind, emigration was emigration, period. I cannot be entirely fair to his view because I did not fully understand it, but the basic point was that Denmark’s independence and greater wealth altered the significance of whatever amount of emigration there may be. Put another way, Mr. Evan’s overall perceptions and expectations about the two countries were so different that they gave entirely different meanings to facts that might appear similar in isolation or in some other context.

The Gallup Poll mentioned earlier did not cover Denmark, but did find that 19% of Finns and 18% of Swedes would like to emigrate. Those results are not in the same class with the figure of 41% in Britain. But they are close to the 22% in Greece, 17% in Brazil and 12% in the United States, and none of those countries is generally considered free from poverty, civil strife, or other troubles.

Nationalists will probably make much of the British figure and, perhaps, of the gap between that and the Scandinavian findings, but little of the others. They will not be hypocritical or see only what they want to see. The British figures confirm or even heighten belief that Britain is in trouble, worse trouble than the smaller nations. The results in Sweden and Finland do not confirm that those countries are incontestably successful, but neither do they suggest that either nation is in a desperate plight.

Scots and Welsh who despair of Britain May not leap to the belief that their own or other small countries could contribute the most to human Progress. But the distance they must jump is considerably if they believe that great contributions have already been made by John Knox and the Kirk, by Adam Smith, David Hume and St. Andrews University, by Clydeside shipbuilders, , by Bobbie Burns and John Macadam and Keir Hardie (or by Methodism and non-conformism in general, by Lloyd George and Aneurin Bevan, by Dylan Thomas, and by Welsh miners.) At the least, their ears are open to the separatist arguments.

(An apt illustration of ear-opening came from the U.S. recently. The Christian Science Monitor reported on March 11 that several newspapers have been reporting as a fact that 28 Black Panthers have been killed by police, but that when Edward Jay Epstein checked up, he confirmed only three killings. Ten or 15 years ago, the Panthers claim might not have been published at all, and certainly not as fact. But beliefs about blacks’ conditions and the police have changed so much that the story is now credible to many people. Other things being as they are, proof or disproof of one case is not likely to change underlying attitudes very much.)

Received in New York on April 1, 1971.

©1971 Scott Keech

Mr. Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.