April 7, 1971

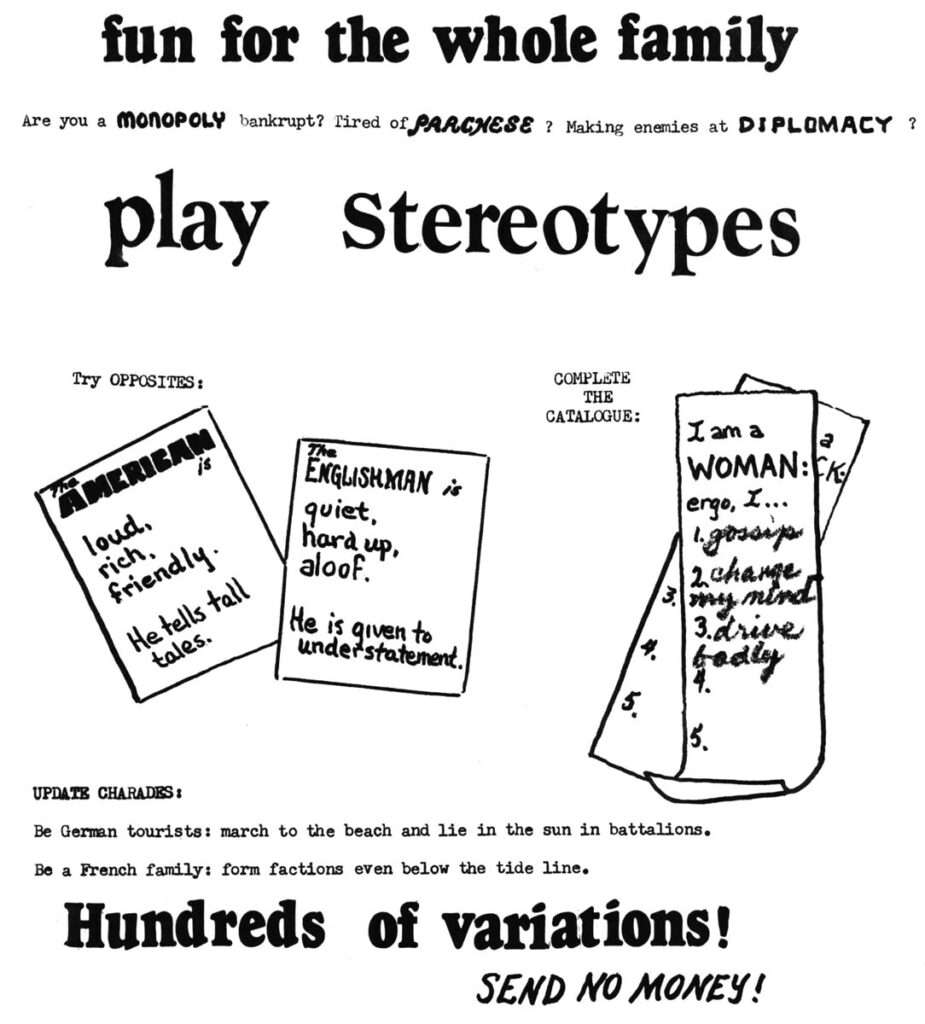

fun for the whole family

Are you a monopoly Bankrupt? Tired of PARCHESE?

Making enemies at DIPLOMACY?

play Stereotypes

| Try OPPOSITE: | COMPLETE THE CATALOGUE: | |

| The AMERICAN is loud, rich, friendly He tells tall tales | The ENGLISHMAN is quiet, hard up, aloof. He is given to understatement. | I am a WOMAN:

|

UPDATE CHARADES:

Be German tourists: march to the beach and lie in the sun in battalions.

Be a French family: form factions even below the tide line.

Hundreds of variations!

SEND NO MONEY

Kindly souls in the United States and in London warned me that the Scottish dialect would be hard to understand.

In Huddersfield, a man whose accent and idiom – rural Yorkshire, someone said – repeatedly baffled me, finally laughed and said, “If you think you have trouble understanding me, wait until you hear the Scots.”

Near Berwick-upon-Tweed, I was reduced to smiling and chuckling inanely at a gas station attendant who was obviously trying to be friendly, and who was otherwise entirely incomprehensible.

A mile or so further on, there came a sign: “Last Pub in England.” It drew a laugh – the first pub in Scotland was all of a mile away, and anyway, both were closed – but a slightly hollow one. The joke would be a painful one if I could not understand a word of the interviews I had scheduled.

In Edinburgh. all went as well as I had anticipated before the dire warnings, but a couple of Scots asked, in that tone that indicates an affirmative reply is expected, if there had been translation difficulties. Told that there had been none, they were sure there would be on the trip to the Highlands.

In fact there were none then either, but the Scots in Edinburgh explained that the problems would have appeared further north and west, in the real Highlands.

A Welsh ten-year-old told the joke – new to him but ancient before his grandfather was born – all versions of which assume that Scots pinch pennies ferociously, and end: “Bang goes sixpence!”

The Scottish National Party press officer looked at the men enthusiastically feeding the slot machines at the Edinburgh Press Club and said that he was “too Scottish” to waste his money that way.

An article on Scottish housing reached the usual conclusion – there is too little of it and too much of that is decrepit and overcrowded. It offered the usual reasons – low incomes and a preference for spending less on housing and more on other things, compared with the English – and one unexpected one. That was that Scots save a higher proportion of their incomes than the English.

When my six-year-old son dropped a penny in an Edinburgh laundromat, the manageress said laughingly that he was obviously not Scottish, for no little Scots boy would let money slip out of his grasp that way. Since her own husband had made a gift of the coin, the irony was inescapable.

Now, we all stereotype or caricature or what-you-may-call-it. But it had never fully penetrated before that stereotypes may be just as much about “Us” as about “Them”.

Baldly stated, it seems crashingly obvious now, and may have been so all along to everyone else. But previously, stereotypes had seemed important only as examples of the kind of thing condemned by sociologist Robert K. Merton in a fine article, “The Self-fulfilling Prophecy.”

Merton was concerned with the sort of dangerous illogic

that can say, for example, that blacks are inferior and must be kept out of medical school, and then cite the small number of black doctors as evidence that blacks are inferior. Then there is what he calls the “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation, in which a group that prides itself on working hard can dismiss outsiders who have achieved less as “lazy” while condemning outsiders who try to achieve as much as “pushy” .These are examples of “moral alchemy” that is neatly summed up in the declension: “I am firm, thou art obstinate, he is pigheaded.”

Seen in this context, the stereotypes that matter involve invidious judgments about outsiders. They are especially pernicious because, by derivation from the field of printing, they disregard individual differences. The holders of stereotypes resist or are oblivious to evidence of exceptions, as in Shirley Jackson’s story, “After You, My Dear Alphonse.”

All of which still seems true, but incomplete. For it appears that essentially the same stereotypes are held about Scots by Scots and by non-Scots.

Quite a collection can be made: Scots are religious, church-ridden, highly educated, narrow-minded, great explorers, suspicious of foreigners, dour, friendly, disputatious or even violent by nature (though the Irish are, by common consent, more so), and of course parsimonious but feckless, as well as puritanical but hard-drinking. I have found every one of these in history books or newspaper articles by both Scots and English.

These are not only the same in denotation, but also in connotation. That is, Scots do not call themselves “frugal” while others call them “tightwads” but both may use either term.

Then, too, the question of evidence is not clear cut. It is true that critical examination of these caricatures often finds them in conflict with each other, and they are in any case generally untrue in the sense that they do not cover all or a majority of actual examples. But it is also true that they seldom fail to describe any cases. Some Scots speak Gaelic, more speak a dialect, and many speak English with a definite and identifiable accent.

Moreover, exceptions can in fact be recognized. (Sometimes with a shock. It seems to flabbergast some Englishmen that an American couple likes soccer. Americans are supposed to like rugby-style football, right?)

Clearly, the Scots I talked to in Edinburgh did not think that they themselves were hard to understand. But they were exceptions. The rule is that the Scottish speak English differently from everyone else, and in a fashion the rest have trouble understanding. (Which perhaps puts a different light on statements like: “This particular American, Catholic, Republican or Negro is all right, but Americans or whatever are in general despicable, dangerous or disgusting.”)

Flexible as these beliefs are, they influence behavior. For one thing, if Scots are always being told that they pinch pennies, many of them may do so – and more may talk as if they do.

Talk matters. A foreigner hearing the chatter I heard in Edinburgh, but without the unmistakable ironies, might easily go away convinced that Scots are universally parsimonious. A native who grew up hearing the same talk frequently might be even more convinced.

For both foreigner and native, “Scot” and “frugal” become nearly synonymous. The image can be found in a wide variety of expressions. Sir Walter Scott used it. Historians refer to it. Television comedians build bits around it. It is there to be used by anyone who needs to evoke a feeling or make a point in a phrase. The user need not fully believe it himself, as the writer of the article excerpted below probably does not believe it but does think it will affect his readers.

By your generosity and that of your friends you can abolish the out-olf-date mean-minded image of the saxpence-banging Scot for whom the of money was a spending your money pain. Let relieve others' pain. P. A. S.

These things have remarkable longevity. That “bang goes saxpence” joke can be found at least as far back as the 1750s. References to Scotsmen’s violent natures, religiosity, wanderlust, etc., are as old. They are part of the culture, of the mental set of a whole group. Stereotypes influence the way we see things and give clues about what facts mean.

A lot of codicils need to be added. All Scots do not hold precisely the same stereotypes and are not affected equally by the ones they do share. But simply knowing the same ones is important. Idiom and allusion, along with accent, dress and skin color, give a stranger an instant personality. The signs tell if he is one of “Us” and predictable, or one of “Them” or “Others” and unpredictable,

(It is a little Off the subject, but the strength of a mental set has been brought home to me by a riddle: A man and his child are in an auto accident. The man is killed, The child is taken to a hospital, seriously injured, and a surgeon is called but looks at the child and says, “I can’t operate, That’s my child.” How can that be? Interestingly, few of the people I have tried the riddle on in San Francisco, New York and London, including men and women who are both politically aware and good at puzzles, saw that the surgeon is the child’s mother.)

The result may be a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Scottish Office (a cabinet-level department of the UK government) was created partly because the Scots felt distinctive. Now its existence is “proof” that they are.

But the result is also to give the Scots a general frame of reference different from that of the English. So, Scotland is not just a region of Britain. Unemployment in the Northeast Region (of England) may be as high as in Scotland, but to Scots the proper comparison is between all of Scotland and all of England.

Unemployment is an issue which may generate great heat anywhere. But in Scotland, or Wales, protest is given an extra dimension by arising in national terms. Then a spiral can be created. An issue raises a protest on behalf of Scotland, which reinforces the sense of difference, which makes it easy to feel misfortunate by comparison with or at the hands of the English, which makes the discovery of other issues and the raising of other grievances more likely…and so on.

What about the other sort of stereotypes, the invidious or prejudiced sort that is expressed in discrimination?

I have some more or less organized thoughts.

For one, prejudice is not necessary for many kinds of discrimination and general abuse of human beings. Slavery, to take an extreme example, has been imposed on Europeans by Europeans, on Africans by Africans, on Africans by Europeans, and so on. (In the late 17th century, serfdom was imposed in fact and in law on salt, lead and coal miners in Scotland. It was maintained

until all slavery was outlawed in Britain in 1770. Miners could have families and could not be sold away from the mines in which they worked, but otherwise their condition and status was not very different from those of black slaves in America.)

Sometimes slavery has been accompanied by a theory that the enslaved are less than human, but not in unique or even very special circumstances. The capacity of individuals and societies to hold what they as well as outsiders consider conflicting beliefs should not be underrated.

In any case, prejudice is not sufficient to cause discrimination. To get away with that, the discriminators must have sufficient power to repress protest. But individuals or groups with tremendous power will almost inevitably discriminate to some degree merely because of their power – the weaker cannot bring their interests to the attention of the stronger with sufficient force to compel taking them into account. More than that, possession of great power induces self-righteousness (We are strong, so we must be doing the right things, and God is on our side.) and makes it easy to dismiss as unimportant or unworthy the self-interests of others which is, I take it, what Lord Acton meant by the aphorism, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The process occurs between groups, within organizations, and in more intimate relationships such as families where young children have no effective comeback against being slapped down or ignored.

Yet prejudice certainly plays a role. Reactions to immigrants – to Europeans as well as Asians in the United States, to the Irish as well as those from the “New Commonwealth” in Britain, to Italians as well as Turks or Algerians in France or Germany – are impressively and depressingly similar. It sometimes seems that sheer difference is enough to cause prejudice. (How else can you explain the antagonism the deaf and the blind report encountering?) But not all prejudices are equally troublesome.

In Northern Ireland today, a man may be lynched because of his religion. In the United States, conflict between Protestants and Catholics or Christians and Jews seems to have declined very greatly. In Glasgow, Protestants, Catholics, officials of all the political parties, journalists and political scientists say that Catholics of Irish descent remain a large, self-conscious and obvious minority, but that prejudice against them, conflict between them and Protestants, and the importance of the “right” religion in certain districts, are all declining. The same is said of Liverpool, another great center for Irish Catholics.

Why is Belfast so different from Glasgow or Boston?

The answer seems clear that in Belfast but not, or at least decreasingly, in the other cities, religious differences coincide with major political and economic divisions. To be Protestant in Northern Ireland is not necessarily to be wealthy or powerful, but the wealthy and powerful are almost entirely Protestant. To be Catholic is to be excluded from positions open to Protestants, to be denied certain civil rights, and to face the near-certainty of sometime encountering discrimination in housing or employment.

Each issue, each set of fears and hatreds, reinforces every other. A sometime sociologist named Ralf Dahrendorf has suggested that conditions of “super-imposition” – when groups find themselves facing the same enemies on many different issues, as in Northern Ireland – are conditions in which violence is most likely to occur.

The more disputes there are, the harder it is to separate out any one Of them for settlement by compromise, and the harder it is to damp down feelings enough to make a compromise acceptable even if one issue can be separated from the mass.

Religion or race or nationality is not necessary for such a viciously circular conflict, but when it is involved, it adds a special difficulty. Compromises may succeed in opening political and economic opportunities. A religion may be granted tolerance, but that does not serve to reduce differences in the same way that broadening political rights does. Still, the point appears to be that if the circle can be broken, then the antagonisms and the potential for violence in the differences that remain are much reduced.

In Britain for the last 200 years or more, national and religious differences among the English, Scots and Welsh have not coincided, or have coincided less and less, with political and economic divisions. Now, the nationalists are trying to recreate such a combination.

Nationalists react strenuously to allegations that nationalism is necessarily xenophobic. Certainly there are few signs of any kind of bigotry among leaders of the two nationalist parties.

But if the nationalists are going to succeed, they must arouse strong Emotions. People simply will not undertake the known and suspected risks of separatism unless they feel terribly strongly about the pains and tribulations of union.

The potential strength of the nationalists depends on the possibility that they may be able to make a general but mild sense of distinctiveness that is valuable into a strong sense of grievance centered on nationality. They must persuade their compatriots that differences among them are less important than similarities, and that similarities between them and the English are less important than differences.

They must also persuade their countrymen that benefits are being foregone and sufferings undergone because of the union with England. The easiest and most obvious way to do that is to emphasize differences in benefits and sufferings between Scotland or Wales and England – in unemployment and income, for example – and to argue that the comparative deprivation exists – and must exist – because of the union with England. From there it is a very short step to attributing problems to England, to the English, to Englishness.

The risk, then, is that if grievances become great enough to make separatism a serious force, patriotism will turn into chauvinism.

Most of the present nationalist leaders seem to distinguish between England and the English and between the effects of policies they consider harmful to Scotland or Wales and the intentions of policy makers.

But if a Scotsman concludes that his country is being “robbed” by the Treasury, he may very naturally go on to think that England is doing the robbing, that the English are robbers, that they will not stop because they do not care about Scotland, and finally that they intend to rob Scotland.

Gwynfor Evans is able to assert that the destruction of Welsh culture is an essentially inadvertent result of the excessive growth of the state apparatus and a bureaucracy which values conformity above all, and of the absence of understanding of and empathy with Welsh culture that must occur among the English who do not know Wales and who have their own culture. Mr. Evans is a gentle man for whom more sorrow than anger is natural.

Some of his followers are angrier. The tone of the Plaid Cymru newspaper is often distinctly unpleasant – government ministers do not merely disagree with the nationalists, they are selling out Wales; census or tax forms in Welsh are not scarce or entirely lacking because of bureaucratic foul-ups, but because the English want to destroy the language, and so on.

One event should not be made into a general theory, but I was jarred by an incident at the Plaid Cymru conference. During debate on education, one speaker called for changing the party’s policy of calling for the teaching of both Welsh and English in all schools, with students free to take either or both. He wanted Plaid Cymru to support compulsory teaching of Welsh to all.

Language is rooted in personality, he said, and Plaid Cymru should make it clear that the days of “the wrong personality” are over.

The personality displayed was not attractive, but it might have been an insignificant fringe view that was expressed. The party did not in fact adopt his view, but it did roundly applaud his statement.

Plaid Cymru and the Scottish Nationalist Party are committed to achieving their aims nonviolently, through elections and negotiations. That means that they must win a majority of the votes and Parliamentary seats in their countries and then persuade the English to agree to separate. If they fail, they must fade away or turn to other means. If they succeed or come close at home, but fail with the English, fading away is not likely.

There are other, non-electoral organizations in the field now. The Welsh Language Society is nonviolent but not non-forcible. It is very militant, engages in sit-ins and other kinds of civil disobedience that must end in police action, and destroys road signs printed in English only. A year or so ago, 30 of its members were in jail.

There is also the Free Wales Army, which is minuscule but violent.

Scotland has no equivalents of either the Language Society or the Free Wales Army, but it is not long since some Scots went in for blowing up post boxes to make clear their opposition to calling the present Queen the second Elizabeth – Elizabeth I was not Queen of Scotland.

Playing with bombs is fashionable these days, but it can be a serious political weapon when enmities go deep. Nationalists run the risk of arousing such enmities.

I have run together in this paper some differences among groups that some readers may feel should be kept apart, and it may be worthwhile to elaborate on the question a little.

The May, 1969, issue of the American Journal of Sociology published an interesting article by Nathan Kantrowitz, “Ethnic and Racial Segregation in the New York Metropolis, 1960.

Using 1960 census data, Mr. Kantrowitz derived an “index of segregation” for various groups. Predictably, the highest figures were found for Puerto Ricans and Negroes; the lowest index between those groups and groups of European origins was 76. The indices between all the groups from northern Europe and all the groups from southern Europe averaged 51. The indices between nationalities within the northern European group and nationalities within the southern European group averaged 41. The index between Norwegians and Swedes was 45.

From these and other figures, Mr. Kantrowitz drew the conclusion that segregation between ethnic groups “remains relatively high into the second generation. This suggests that white resistance to racial integration may but compound the strong separatism of ethnic populations…. Certainly for the present, the strong prejudice against Negroes only compounds existing separatism, for if Protestant Norwegians hesitate to integrate with Protestant Swedes, and Catholic Italians with Catholic Irish, then these groups are even less likely to accept Negro neighbors.”

That may be true (although hesitating to integrate may not be precisely the same as declining to accept neighbors), but the figures may also have other implications.

To someone who is neither Swedish nor Norwegian, the differences between those two groups, in the United States, seem vanishingly small, but to members of both groups the differences are evidently large enough to be significant in influencing housing patterns. That index of segregation was astonishing, and it brought home with great force the ability of a group to maintain its identity and its distinctiveness from others and from the whole society. (For Norwegians the index between them and Swedes was lower than any other; for Swedes the indices were lower for three of the other 12 groups surveyed.)

The kind of segregation that exists between Norwegians and Swedes is obviously not the same as segregation by law or by custom backed by violence. But it started me toward the conclusion that any difference may be made significant but that any difference can also, in time and in the absence of other serious disputes between groups, become sufficiently familiar and acceptable to stop being a focus of hostility and prejudice.

A previous newsletter (SK-2) reported on a debate over whether ethnic and racial conflicts are fundamentally unlike. I do not think they are.

Physical appearance is certainly striking. But unless one accepts the argument that appearance is a sign of intellectual, emotional or moral quality – which is biological nonsense – I can see no reason to believe that skin colors cannot be as noticeable but as unlikely to cause social strife as hair colors.

It is perhaps only a failure of my understanding, but I cannot see that racial categories are necessarily more artificial or invidious than other sorts of categories. Nor can I see that conflict between “races”, is necessarily more serious than between other groups.

The artificiality and arrogance of judging that one form of worship is pleasing to God are surely as great as in judging the worth of a group in this world by skin color. And the struggle between, say, European Protestants and Catholics in the 16th and l7th centuries was not less bitter or easier to resolve than the struggle between American blacks and whites now.

I cannot see critical differences in the origins of the race riot in Cardiff in 1919 and the more or less contemporary “Orange and Green” riots in Glasgow or Liverpool. Nor can I see that the differences are more important than the similarities between the revolting events revoltingly named “Paki-bashing” and “queer-bashing” by teen gangs that beat up individuals they think are Pakistanis or homosexuals.

In each case, it appears to be less important how any identifiable group differs than that there is an identifiable group which can become the focus for other grievances.

Common grievances concern housing and jobs. In Britain, for example, there is ample evidence that all of the centers in which immigrants have settled had housing shortages before they had many immigrants. The immigrants did not create the shortages, though they may have exacerbated them. To blame immigrants was no doubt to pick out the least important factor and to divert attention from more important ones, but it was not to be simply and solely racist. Again, it is no coincidence that the belief that Britain did not and would not have racial problems like those in the United States went into abrupt decline, not when immigration first became substantial, but when the severe shortage of workers ended in the early 1960s.

I do not think reactions would have been much greater if the immigrants had not been colored. So far as I can see, reactions to Irish immigrants 100 years ago were very similar.

Both ethnic and racial differences can serve to identify and to symbolize enemies, or to suggest scapegoats for inquisitions or pogroms or revolutionary terror. But conflict, like most things, has multiple causes. Ethnic or racial difference can be one of them, but neither need be one of them.

N.B. The art work in this, as in previous newsletters, is by Catharine Lucas Keech.

Received in New York on April 14, 1971.

12 Southwell Gardens

London,

SW 7

©1971 Scott Keech

Mr. Keech, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, This article may be published with credit to Mr. Keech and the Alicia Patterson Fund.