How a grassroots groundswell, legal challenges and political and technological sea changes combined to force Virginia’s most powerful company to abandon the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, pivot from natural gas and onto a cleaner energy path.

“Hung up in the mountains”

Tom Hadwin took a sip of water and looked out at his audience, arrayed in folding camp chairs in the middle of a leafy grove at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, waiting for him to continue his multi-part indictment of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

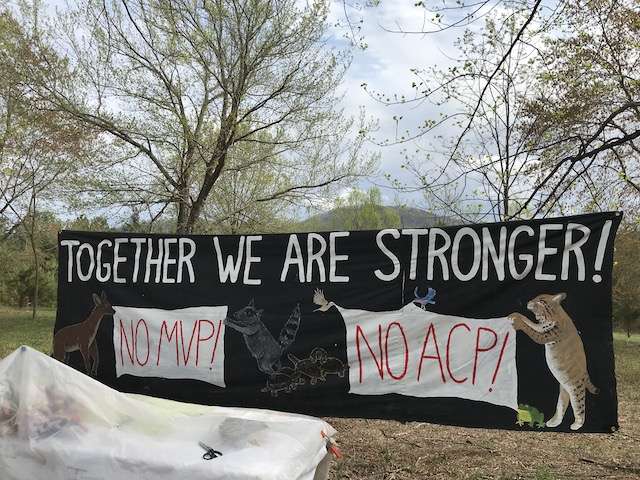

The assembled activists were mostly retirement-age, like him, with a couple dozen millennials among them. Many sported blue t-shirts with “NO PIPELINE” emblazoned on the front. Nearby, under tarps strung up for shade, a table was strewn with fact sheets tallying the economic and climate damage that would be wrought by the pipeline, if it were ever built. A banner flapped from a plywood shelter. Its message, “PROTECT AND DEFEND,” aptly captured the mood of focused, quiet outrage.

The ACP would be just the latest piece of plumbing in the nation’s fast-growing network of natural gas infrastructure – with more than 200 new gas-fired power plants either planned or under construction around the country, and thousands of miles of new gas pipelines permitted and planned for the Appalachian Basin alone.

For 27 of its 600 proposed miles, the natural gas pipeline was slated to cut a 125-foot-wide right-of-way through the heart of Nelson County. The area is a rural swath of central Virginia, home to about 15,000 people nestled in the hollows, river bottoms and wooded slopes of the Blue Ridge and its foothills. Friends of Nelson, a citizens’ group wholly dedicated to stopping the pipeline, had organized the gathering as a way to rally its members after five long years of fighting the flagship project of Dominion Energy, based in Richmond. This forested 100-acre parcel, owned by Richard and Jill Averitt, the workshop’s hosts, seemed like a symbolically rich place to do it. Dominion’s planned route for the project ran straight through the ground on which Hadwin stood.

Throughout the day, the tone of the gathering had evoked a strategy session at an outpost of an army fighting off an invading force, combined with the exhortations of a home team locker room at half-time.

Hadwin, who finally got up to speak around 4:00 p.m., after several other speakers and a few rain showers had passed through, was the general rallying the troops.

“Okay, so here’s the Atlantic Coast Pipeline,” said the courtly former utility executive, clad in khakis, loafers and a blue button-down shirt, pointing at a red line on a posterboard map.

The red line snaked its way southeast through the heart of Virginia, marking the route by which Dominion and Duke Energy – the other corporation behind the ACP – dreamt of transporting gas via a 42-inch-wide pipe from the fracking fields of West Virginia, through the Shenandoah Valley, over the Blue Ridge, under the James River and onward to more densely populated eastern Virginia and North Carolina.

“We talked about how it’s getting hung up coming from West Virginia through the mountains, for all the legal reasons that were discussed earlier,” Hadwin continued.

“Dominion sees that it’s hung up. And they arestunned by this.”

Several people cheered and clapped. It was April 2019, and tree-felling and excavation work all along the pipeline route had been halted, thanks to the legal challenges Hadwin mentioned. The previous December, a federal appeals court had thrown out the project’s permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to build in areas inhabited by endangered species. Another key permit from the U.S. Forest Service, to cross two national forests and under the iconic Appalachian Trail, also had been vacated. Both successful cases were brought by the Charlottesville-based Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), which represented Friends of Nelson and 14 other grassroots and environmental groups as its clients in a range of legal challenges to the pipeline.

“I’ve talked to people who worked at Dominion,” Hadwin continued. “They said, ‘We didn’t expect any of this.’”

Joyce Burton had listened intently throughout the afternoon as Hadwin made his case, countering Dominion’s longstanding narrative that the project would lower energy bills, create thousands of jobs and offer a critical boost to economic development in eastern Virginia and North Carolina. On the contrary, he argued, there was no energy affordability rationale for building the pipeline and no desperately surging but unmet gas demand in those areas, either. It was a pure profit play. Dominion was guaranteed by law a generous 14 percent rate of return on the capital investments it made. If it built the pipeline, it could pass along the costs to captive utility ratepayers, to the combined tune of $30 billion added to their monthly bills over the next 20 years. “They only care about how much they can charge us for the pipeline,” he said.

It was an argument Hadwin had delivered to dozens of meetings, rallies, and in writing to investors, elected officials, Dominion shareholders and members of various state and federal regulatory agencies since he first waded out of retirement in nearby Waynesboro, and into the fight in 2014. “As a former utility executive, I’m embarrassed for the energy industry,” he said. “Everyone in Virginia and North Carolina will pay higher rates, and for the damage these projects cause.”

Burton had written her fair share of letters and comments to agencies, too, over the past five years. She had left her career as a physical therapist not long after the project was announced to become a full-time volunteer for Friends of Nelson, organizing landowners along the route in opposition, serving on the group’s board, tracking every easement signed with Dominion. Burton peppered Hadwin with friendly but pointed questions about regulatory arcana – details of process by which the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reviews permit applications for major interstate energy infrastructure projects in the U.S., and the workings of the State Corporation Commission (SCC), which regulates public utilities in Virginia – and the economic motives driving the companies’ increasingly frantic push to get 1.5 billion cubic feet of gas flowing per day through that sun-dappled field.

Burton wanted to know what Dominion – Virginia’s biggest electricity utility and its most powerful corporation, and with a 53 percent stake, the pipeline’s majority owner – was going to do next.

Hadwin nodded. “Investors are asking tough questions about this,” he said. “They are being hammered, telling investors it will all work out.” Every day of delay brought rising costs, and ratcheted up the pressure from shareholders, he added. The project’s backers had to come up with a solution fast.

Dominion and Duke had recently announced their intent to appeal to the Supreme Court a lower circuit court’s ruling invalidating its permit to cross the Appalachian Trail. In earnings calls with investment analysts, their executives had insinuated that they would lobby members of Congress for “legislative remedies” – an end-run around the pileup of permitting roadblocks – if the high court denied their appeal. Meanwhile, while it was “hung up” in the mountains, Dominion was eager to start construction of the eastern section of the pipeline that fall. A large compressor station it wanted to build in Union Hill, an historic, 150-year-old Black community in neighboring Buckingham County, was essential to that plan.

“Dominion has been great at controlling the narrative,” said Hadwin. “It’s all about ‘jobs and keeping the lights on.’ Dominion has the best lobbyists, former FERC and EPA leaders. They are determined. But Dominion is surprised that their playbook isn’t working.”

A little over a year later, it was Joyce Burton’s turn to be surprised. On July 5, 2020 – late on a Sunday afternoon of a holiday weekend in the midst of a pandemic – Dominion and Duke announced that they were finally abandoning the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

After six years of mounting opposition, increasing scrutiny from lawmakers, regulators and investors, and a series of legal challenges that led to delays that drove the price tag of the project from an initial $5 billion to more than $8 billion, two of the most powerful utilities in the country were throwing in the towel. Ongoing litigation risks, the two companies said in a joint statement, “make the project too uncertain to justify investing more shareholder capital.”

“I’m afraid I’m developing a bruise on my arm from pinching myself,” Burton told me the next day. “It’s so incredible that we all actually pulled this thing off.” She had spent the previous evening calling and texting landowners along the pipeline’s path, to deliver the news. “Some of them were literally sobbing, saying they can’t believe the mountains are safe.”

The news also took a while to sink in for Greg Buppert. He is a senior attorney at SELC, which represented 15 different grassroots organizations and environmental groups in a range of lawsuits against the pipeline, Dominion and various state and federal agencies that issued permits for the project.

“When D.J. Gerken called me on Sunday afternoon, I just found it very hard to believe that this was happening,” said Buppert. “My feelings were surprise and disbelief.”

Gerken, a fellow senior attorney at SELC, was the lead litigator on several permit challenges, including the USFS and Fish and Wildlife “biological opinion” cases. Buppert was the principal architect of the multi-front legal strategy against the pipeline.

Since they took on their first pipeline opponent clients in 2014, the two lawyers and dozens of fellow SELC staffers logged more than 40,000 hours of attorney time and $1.6 million in expenses. They won case after case in the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond.

“For six years the deck was stacked against the communities, landowners and organizations opposed to this project,” Buppert told me. “Despite those overwhelming odds, the resistance and opposition to the project only grew stronger. All of those things together forced this project off the table and onto the scrap heap.”

With its demise, the consensus view of natural gas as a “bridge” to a renewably-powered future may have received a fatal blow, too.

In the wake of the ACP’s cancellation, a shudder went through the wider oil and gas and utility industries. Leaders of major energy firms wondered out loud if the natural gas party was over. It didn’t help that the coronavirus pandemic had crushed demand for oil and natural gas to record lows, and during the same week that federal judges vacated key permits needed by two other large, controversial pipeline projects, the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines.

“Is This the End of New Pipelines?” wondered the New York Times in a story headline a few days after ACP’s demise. By the following month, John McAvoy, the CEO of ConEd, one of the nation’s biggest utilities, said it would no longer invest in long-haul gas pipelines, and might sell its ownership stake in the Mountain Valley Pipeline. “We made those investments five to seven years ago, and at that time we — and frankly many others — viewed natural gas as having a fairly large role in the transition to the clean energy economy. That view has largely changed, and natural gas, while it can provide emissions reductions, is no longer … part of the longer-term view.”

On the same day as the ACP cancellation, Dominion announced it was selling more than 7,700 miles of gas pipelines, 900 billion cubic feet of gas storage assets, and a share in its Cove Point LNG terminal in Maryland to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy. (With the purchase, Buffett now owns 18% of all natural gas transmission lines in the U.S. He was not interested, however, in purchasing Dominion’s stake in the ACP.) In one fell swoop, Dominion’s offloaded a huge part of its natural gas business. It still retains local gas distribution networks in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Ohio, Utah and West Virginia. The company seemed to be conceding that its long-held bets on natural gas as the fuel of the future hadn’t paid off, and that it was time to cut its losses and move on.

“To state the obvious, permitting for gas transmission and storage has become increasingly litigious, uncertain and costly,” CEO Tom Farrell remarked to investment analysts, in a call the day after the cancellation.

Dominion leadership seemed to make this move grudgingly, said David Pomerantz, executive director of the utility watchdog Energy and Policy Institute.

“Their hand was forced,” he said, by a grassroots movement concerned about both climate change and the use of eminent domain to seize land, by a historic shift to Democratic control of Virginia’s legislature in the 2019 election, and by an ambitious new climate bill, the Virginia Clean Economy Act, passed by those legislators in March.

“The gas industry has been lighting its hair on fire for years saying that it’s become impossible to build gas pipelines” due to regulatory and legal roadblocks, Pomerantz said. “I don’t think they’re wrong about it becoming increasingly difficult. That’s a credit to a lot of lawyers, certainly, but also a lot of activists who are working without pay to protect their homes and their land.”

“They cast aspersions on us, refer to us as radical troublemakers,” said Doug Wellman, the president of Friends of Nelson. “The fact is, they effectively said, ‘This group of citizens has power and they exercised that.’ That’s a huge part of why I feel so good about where we came out of this. A group of citizens took on two of the most powerful corporations in the energy business and helped stop them.”

“The Campaign to Elect a Pipeline”

Six years ago, the odds that those citizens would succeed seemed impossibly slim.

On September 16, 2014, a long line snaked out the door of the Nelson Center. Dominion had rented the multi-use event space on Route 29 south of Lovingston, the county seat, to hold an open house information session for the interested public. A couple hundred Nelsonians showed up. Dominion employees handed out fact sheets outlining an ambitious timetable: finish route planning and surveying by the end of 2014; secure FERC certificate by summer 2016; construction the following year; pipeline “in-service” by late 2018.

Dominion’s executives had reason to be confident. Of the 470 applications for pipelines it had reviewed in the previous 20 years, FERC had rejected only two.

And, Virginia’s state legislators and regulators at the SCC had a long record of friendly, pliant oversight of the powerful utility.

Two weeks earlier, Governor Terry McAuliffe had stood alongside Dominion Energy CEO Tom Farrell at a press conference in Richmond and, with a grin and a handshake, announced his support for the $5 billion pipeline. “The proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline will be a huge asset to Governor McAuliffe and his team as they work to create jobs and build a new Virginia economy,” the state’s press release read.

The governor’s stance drew the immediate ire of big environmental organizations like the Sierra Club and Natural Resources Defense Council, but observers of Richmond weren’t surprised. Dominion held bipartisan sway in Virginia’s capital.

Dominion is widely acknowledged to be the most politically influential corporation in Virginia. Over the past 20 years, it has been the top political corporate donor in the state, taking advantage of Virginia’s unusually lax campaign finance laws to spend in support of candidates for the state House and Senate, on both sides of the aisle. Dominion was one of the biggest donors to McAuliffe, giving $50,000 to his inaugural committee alone in 2013.

With justification, veteran political scientist Bob Holsworth told the Washington Post that McAuliffe had made a simple calculation: “It isn’t a political liability until we see that these environmental groups are able to develop grassroots traction to be able to successfully oppose this.”

Similarly, a Dominion employee wasn’t being hyperbolic when he told landowners along the path to quickly sign easement agreements because, “We’re a billion dollar company, and we’re going to put the pipeline wherever we want to put it.”

Dominion Energy is valued currently as a $67-billion company. It is the second largest utility in the U.S. in size, and the second most profitable. Its electric utility subsidiary, Dominion Virginia Power, has a monopoly on electricity provision to two-thirds of all of the state’s residents. State laws guarantee the company a 10 percent rate of return on its assets. It has an army of lobbyists and lawyers on retainer, and ready access to cheap capital from investors and Wall Street banks.

“I have had representative after representative look me in the face and say, ‘We’re just gonna vote the way Dominion wants, you can’t stop them, they more or less own the state,’” Richard Averitt told his fellow activists gathered in his field that April Saturday. “It makes my head pop.”

“They were always able to bulldoze their way to what they wanted,” Hadwin told me. Having its flagship project stall in the mountains was perplexing. Dominion and Duke simply didn’t account for just how challenging the human, political and economic terrain would prove to be.

There were signs of significant grassroots traction from the very beginning. By the time of the September open house, Nelson residents had been organizing for months.

Friends of Nelson (FON) was born almost as soon as the project was made public. It was just one of several groups that sprang up in opposition in Nelson County, representing different demographics and a range of tactical preferences. There was Free Nelson, All Pain No Gain, Pipeline Education Group and Friends of Wintergreen – the latter formed by well-off vacation homeowners at the Wintergreen ski resort, one of the county’s major economic engines.

Many people first learned about the pipeline when they received letters notifying them that Dominion’s surveyors would soon be showing up on their property. On June 8, 2014, more than 120 people crowded into the public library in Lovingston to discuss the pipeline, which was first floated publicly in May.

Two weeks later, 150 people assembled at the Rockfish Valley Community Center to start planning their resistance.

By early July, FON members had formed committees dedicated to monitoring the route, environmental impacts, communications and legal issues.

By August, Nelsonians were writing letters to FERC registering their opposition to the pipeline and its route. This was before the pipeline’s backers had even applied for “pre-filing,” the first step in getting the agency’s approval.

By September, in what would be the first of many lawsuits, a group of five plaintiffs from Nelson County sued Dominion Transmission in U.S. District Court, seeking to prevent surveying on their property without permission.

FON members held regular protests outside Dominion headquarters and branch offices, marched on FERC’s headquarters in D.C., staged concerts and social media campaigns, and even helped launch a citizen-led effort called the Pipeline Surveillance Initiative to monitor construction along the route using drones and GIS mapping technology.

FON was just one of more than 50 organizations that sprung up or banded together, from the West Virginia border to the majority Black and Native American communities that the southeast sections of the pipeline would cut through, as part of the Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance.

The pipeline turned people into unlikely activists and odd bedfellows: libertarians and local officials, old-school environmentalists and the climate-concerned, farmers and ranchers and church pastors and brewery owners. They were prompted to speak by a range of concerns, from the risks of explosions from leaks or landslides, to the use of eminent domain to seize private property, to the project’s locking in of greenhouse gas emissions for decades to come.

“We were able to build a coalition of people who work together even though their motivations may have been different,” said Burton.

Dominion did not fail to notice these stirrings. But it seemed to have the situation in hand. Its leaders felt secure enough to pass along friendly advice to fellow energy industry members on how to deal with anti-pipeline activists. In October 2017, at an American Gas Association conference in Scottsdale, Arizona, Bruce McKay, Dominion’s senior energy policy director (ie, in-house lobbyist) revealed some pages from that playbook.

In a presentation for a panel on securing energy infrastructure, McKay shared with fellow industry insiders some key features of what he labeled Dominion’s ongoing “campaign to elect a pipeline.” McKay ticked off that campaign’s milestones: 150 letters to the editor (“If you want fair media coverage you need to pay for it”), more than 9,000 letters and cards mailed to FERC and elected officials, 11,000 phone calls to then-Governor Terry McAuliffe and Virginia’s two Democratic Senators, and 250,000 pieces of direct mail taking the sales pitch of low energy prices and more jobs to Virginians.

Later that week, that campaign’s victory seemed to be at hand, when FERC issued a certificate of approval for the ACP and for its twin, the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a 300-mile-long long project through southwest Virginia, advanced by a different suite of energy companies, that also aimed to bring fracked gas from West Virginia to North Carolina.

“We cannot just sit back and hope for the best and hope that the merit of our project will sell itself,” McKay told the Washington Post in an interview the following month. “Nowadays [regulators] are being bombarded by general citizenry, by elected officials who have asked to insert themselves into the process, and this debate swirls around.”

Dominion leaders predicted the pipeline would be up and running by late 2019. In March of 2018, crews felled trees just below Reeds Gap atop the Blue Ridge, at the spot where the pipeline would tunnel under the Appalachian Trail and Blue Ridge Parkway. Joyce Burton and other FON volunteers gathered, dejected but determined, to hold a vigil of sorts over the tangle of downed timber.

“They Didn’t Count on Us”

That deforested patch would prove to be the pipeline’s literal and figurative high point.

By the end of 2018, instead of being in service, the project was in limbo. Just a few miles of pipe were in the ground.

The month of December was particularly laden with setbacks for Dominion and Duke. On December 8, 2018, all work was stopped when the federal 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the biological opinion issued by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, to allow the pipeline to cut through endangered species’ habitat, was flawed and therefore invalid. “In fast-tracking its decisions, the agency seems to have lost sight of its mandate under the Endangered Species Act,” the judges wrote.

On December 13, the same court ruled that the US Forest Service permit – to cross two national forests and the Appalachian Trail – had been issued improperly. That permit was thrown out, too. The ruling quoted Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax in faulting the USFS for failing to properly consider the full environmental impact on public lands: “We trust the United States Forest Service to ‘speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.”

It was a very good month for the lawyers at Southern Environmental Law Center. “My metaphor internally was jumping rooftop to rooftop and having to hit every one or we’re dead,” said D.J. Gerken.

“These pipelines are often built before anyone gets their day in court,” he said. “We couldn’t miss a single shot. If we did, the pipeline would be 100 percent complete before the key questions of need and whether it’s just a boondoggle would ever get aired.”

In a sense, law center’s legal campaign was a race to stall. By mustering opposition along every weak point – wherever permitting agencies hadn’t done their homework as required by federal statutes like the Endangered Species Act – they could drag out the construction timetable long enough to allow courts to study the fundamental question of whether the project was indeed, as FERC had determined, in the broader public interest.

The vast majority of oil and gas pipeline projects follow a very different pattern. The more of a pipeline that gets built, the easier it becomes for its developers to get regulators and federal agencies to green-light the rest of the project’s completion. As more pipe gets buried, they become, in essence, self-fulfilling prophecies – even before all the necessary air and water quality approvals and easements are secured.

“What this took to get a different outcome from what has too often too long been the outcome for these pipeline projects,” said Gerken, “was a massive investment by landowners, a huge shoving at every door Dominion was trying to walk through to cram this thing through.”

Since 2014, his colleague Greg Buppert had coordinated with law center client organizations up and down the length of the route, attending public meetings large and small, in community centers and libraries and on front porches from West Virginia to North Carolina. His verdict: “Nelson County has always been the emotional backbone of the opposition to the ACP.”

From where he sat, Jesse Rutherford, concurred. “You look at where pipeline opposition exists, and Nelson County is ground zero,” said the 27-year-old real estate agent and home builder, and youngest of the five elected members of Nelson County’s Board of Supervisors. “You ask any contractor working with Dominion, they’d say, ‘Nelson County is going to be interesting.’

Rutherford, a Republican, opposed the pipeline ever since he won his race to join the board of supervisors in 2017. He argued that it violates the property rights of his constituents in order to generate returns for the shareholders of a distant and powerful for-profit corporation.

“I’m an anti-eminent domain usage guy,” he told me, “and I don’t see the public good in this.”

On December 27, 2018, Rutherford and fellow supervisors voted to put together an amicus brief supporting a larger legal action brought by the environmental law center. It called for the FERC to revoke its permit for the entire project, contending the entire economic rationale is fundamentally flawed, and based on unrealistic projections of future energy demand. The minutes of that meeting contained a revealing detail. The supervisors resolved that no more than $1,000 would be spent putting together a brief. Nelson County does not have an army of white-shoe lawyers. But, as Rutherford told me, Nelson wouldn’t be bullied, either.

“SELC has been amazing in challenging every single permit, anywhere they see a slight crack in the legal armor, they’ve pushed at it,” said Lorne Stockman, a senior research analyst at Oil Change International who has authored reports on the climate and economic impacts of the U.S. ongoing natural gas infrastructure boom. “And lo and behold, what they’ve uncovered is a regulatory culture that ignores its key mandate to oversee the industry, and ACP is a prime example of that. Because it’s crossed public lands that are not suitable for that kind of project. And it chose a site for its compressor station that just happened to be in the heart of a poor Black community.”

“It’s hard to overestimate what a significant and persistent factor that arrogant route choice was at every turn,” said Gerken.

One of the key mistakes that Dominion planners made, he said, was to bring the pipeline through more than 20 miles of the Monongahela and George Washington National Forests. “If they were hoping for reduced public opposition by cutting through the forest, that was a major miscalculation. That forest is loved. To use a military metaphor, they were attacking at our strongest point of defense. And then they still had all those private landowners to contend with, too. It was, in the end, a tragic choice for them.”

Rutherford had a trenchant take on why the company made that choice. The pipeline’s planners were “trying to take the path of least resistance.”

“They targeted impoverished areas that won’t protest as much,” he said. “But they didn’t count on us.”

Even in 2014, after the original route was shifted a few miles further south of the community where she lives, Joyce Burton continued to organize her neighbors against the pipeline, including landowners coming under intense pressure from Dominion representatives to sign easements for the pipeline to cross their land.

“It’s still wrong when it’s going through somebody else’s property,” she told me. “How do you justify stepping out of the fight when it’s going on elsewhere?”

Burton went door-to-door to find out who had signed easements with Dominion. The company wouldn’t make all of them public, to maintain negotiating leverage. She learned GIS mapping and trekked across unnamed mountains with soil scientists to survey landslide risk. She and other FON volunteers became self-taught experts in mapping tools and the arcane points of Virginia eminent domain laws and the practice of “quick-take,” by which Dominion could seize land with a court’s approval before settling on financial compensation for the landowner.

Dominion signed hundreds of easements in Nelson County alone. But that process, said Burton, created deep mistrust among residents. Many felt they had no choice but to sign. The specter of eminent domain – Virginia law grants companies the power to seize private land, as long as the owner is compensated under court approval – loomed over every interaction with Dominion employees who came to negotiate access for surveying and deals for easements for the pipe to cross their land.

“I’ve kept a log of amounts different landowners have gotten, by the square foot,” she said. “They range so radically depending on how hard people negotiate, and whether they had lawyers helping them.” Many landowners weren’t in a position to hire legal representation, and settled for compensation far below what comparable properties received. “They will show up with their appraisers, with a lowball offer. You have to hire an appraiser to get a better sense of what you’re going to be losing.”

“Dominion walked into this thinking of itself as king of the hill, unassailable in public eye,” Burton said. “It put out a glossy brochure saying we need this, this will create jobs. People’s initial impulse was to believe that. Over time, we saw more and more egregious things they were putting into their official documentation, and the ways they were treating landowners. Dominion’s reputation was damaged among many people. People see the whole county as impacted, not just their own property.”

Taken together, these tactics wound up alienating many people who weren’t initially passionate opponents, and unifying people who weren’t ideologically or politically aligned.

“It’s a big potluck of arguments: climate and environment, eminent domain, the principle of a for-profit corporation that will benefit,” said Rutherford. “The left-wing environmentalists and the right-wing libertarians who take property rights very seriously – this is the first time I’ve seen those two groups link arms.”

By bringing the fossil gas pipeline through people’s backyards – and insisting on a route that required hundreds of easements on private land instead of using existing rights-of-way – Dominion invited a level of scrutiny of its operations and assumptions about the energy future that it had never experienced before.

“Dominion has been effective in creating a ‘this is an energy independence fight against tree-hugging eco-nuts’ – that’s their whole thing all along and they managed to sell that,” said Richard Averitt, who grew up the son of a Marine colonel in what he described as a right-wing household. “Had Dominion started this project by saying we won’t use eminent domain, we’ll negotiate our way to the coast… I probably wouldn’t be in this fight today. And I regret that, because I think that I now know enough to know there are many other reasons to not want this pipeline.”

“A Concession to Reality”

Among those reasons was the fact that the core justification Dominion offered in its application to FERC for building the pipeline had disappeared.

In its application to FERC, the pipeline’s backers cited several planned new gas power plants on the drawing boards in Virginia and North Carolina that would use 80 percent of the gas flowing through the pipeline.

To demonstrate economic need for the project, Duke and Dominion only had to show FERC that they signed “off-take” contracts for the natural gas the pipeline would eventually deliver. The vast majority of the pipeline’s capacity was booked for subsidiaries owned by the utilities. Effectively, the builders of the pipeline were selling gas to themselves – and in the process they would be guaranteed a 14% rate of return on the cost of the project.

In a neatly closed circuit that almost entirely offloaded the financial risk, those utilities could pass the costs – including the costs of financing the project – onto their ratepayers, who would pay them off on their monthly electric bills for decades to come.

Meanwhile, demand for electricity in Virginia and North Carolina has been more or less flat for the past several years. In response, year after year Dominion and Duke have had to lower their forecasts for load growth – though still coming in with inflated estimates, as the State Corporation Commission, which regulates energy producers in Virginia, recently rebuked Dominion for doing. In 2019, the companies admitted to their regulators that those gas power plants wouldn’t be built. Solar generation, one Dominion executive told Reuters, was just too cheap for gas combined-cycle power plant vendors to compete.

In 2018, Dominion’s long-term Integrated Resource Plan had it building at least eight new gas-fired power plants in Virginia by 2033, with a capacity of 3,664 megawatts. Those plants were in addition to the four new combined-cycle gas plants, totaling 4865 megawatts, that the SCC had approved and Dominion had built since 2011.

By 2020, plans to build those new gas power plants were scrapped. Its new plan called for just 970 megawatts of gas peaker plants to “maintain reliability.”

But those abandoned plants, along with several proposed by Duke Energy that were shelved indefinitely, were the core justification for building the ACP.

December 2018 brought Dominion yet another piece of bad news. For the first time ever, the State Corporation Commission rejected Dominion’s long-range plan, saying the utility hadn’t done enough to investigate lower-cost alternatives, and had left key programs out of its modeling – such as expanding energy efficiency programs and battery storage pilots. The move signaled that state regulators were newly willing to scrutinize Dominion’s assumptions.

In its notice rejecting Dominion’s plan, the state also expressed “considerable doubt regarding the accuracy and reasonableness of the Company’s load forecast for use to predict future energy and peak load requirements.” Those forecasts were a key justification for the pipeline.

Dominion had long contended that the pipeline was needed to supply new gas-fired power plants and to relieve supply bottlenecks for coastal population centers like Hampton Roads. The pipeline, it argued, would help natural gas continue to supplant coal on the grid, even as it would serve to balance the growing amount of renewables like wind and solar coming online, especially at times of peak demand when the sun wasn’t shining or the wind wasn’t blowing.

When I spoke with Aaron Ruby, Dominion’s media relations manager, about the project in November 2019, the theme he emphasized was reliability.

“For the foreseeable future, natural gas is an essential partner with renewables for building a low-carbon future,” said Ruby. “Renewables are inherently intermittent. They have a 35 percent capacity factor. We have an obligation to deliver reliability for our customers.”

“I think the need for ACP is even stronger today than we when we announced it five years ago,” Ruby said. “The infrastructure that’s serving Virginia and North Carolina today is very congested. It’s not keeping up with peak demand. As more renewables come online and natural gas peaking facilities come online, demand for natural gas is only going to grow. We have to have a reliable infrastructure system to support that (pairing with renewables).”

“Natural gas is easily and quickly dispatchable,” he continued. “You can ramp up or down a natural gas combustion turbine plant within minutes to be able to put electric load on the grid when the sun goes behind the clouds or the wind stops blowing.”

His comments were in keeping with those of other Dominion executives, such as Katherine Bond, its vice president for public policy and state affairs. The executives relentlessly have framed the pipeline as essential to meeting Dominion’s primary responsibility to customers in keeping the lights on.

“Natural gas is the perfect partner for renewables,” Ruby said. “As electricity generated from wind and solar are varying throughout the day, you can meet the real-time needs from the grid.

“Our company is investing in battery storage pilot projects, there’s a lot of potential there, but the technology hasn’t evolved on the scale to be economical at this point,” said Ruby.

Dominion is far from alone among major utilities in contending that renewables and battery storage are not ready for prime time, and that more natural gas generation will be needed to back up wind and solar plants. Duke, Southern Company and Entergy have all remained committed to building new gas plants, even as the cost of wind and solar continue to plunge. All are based in the Southeast. They also tend to share this outlook, articulated by Ruby: “Natural gas will continue to be an essential part of the low-carbon future for many years to come.”

Proffering natural gas as a climate solution has been a popular position ever since President Barack Obama touted it in his State of the Union address in 2013, heralding his administration’s All of the Above energy policy, which emphasized the benefits of cheap natural gas to encourage switching from coal-fired power.

But two trends over the past decade have undercut that narrative. One is that multiple studies, using satellites and ground-based sensors and sophisticated modeling, have found that methane is leaking from oil and gas wells, compressors, storage tanks and pipelines and local distribution networks – even from appliances at the end of the supply chain in people’s kitchens and basements – at far higher rates than previously estimated.

The second is that renewables and battery storage costs have dropped much faster than experts predicted.

Energy experts at U.C. Berkeley and GridLab, a think tank, recently conducted an extensive modeling study that concluded it is possible to create a 90 percent zero-carbon U.S. electricity system by 2035, while actually lowering electricity rates by 10 percent from today’s levels – all without building a single new gas power plant. In their model, to achieve a 90% carbon-free grid, existing natural gas generation would go down by 70%, and its overall share of U.S. capacity would decline from 37% today to 10%.

Amol Phadke, a researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, was a lead author of the report. He argues that the U.S. doesn’t need a single new gas-fired power plant.

“You don’t need to build new natural gas plants for any reliability or dependability reasons,” Phadke told me. “There’s enough existing gas, and cheap storage available.”

His model showed that, for a 90 percent clean grid, between 300 to 350 gigawatts (a gigawatt equals 1,000 megawatts) of gas-fired capacity will be needed to cover those times when solar and wind production is down. “We already have close to 500GW gas capacity built in the U.S. If we are to decarbonize, we don’t need the new (plants) in the pipeline. Ideally they shouldn’t be built.”

“Natural gas only looks cheaper if you don’t factor in those environmental costs,” said Phadke. His point is that, if the climate and other environmental impacts of burning fossil carbon were incorporated into the price of gas-fired electricity, it couldn’t come close to competing with renewables. “From an economic perspective, if natural gas was paying for its fair share of environmental costs, then it’s simply not economical to build new gas plants.”

What’s remarkable is that it may not be economical to build those plants, even without accounting for their environmental and climate costs, according to recent research from the Rocky Mountain Institute, a non-profit energy think tank.

Institute researchers Chaz Teplin and Mark Dyson looked at 88 proposed gas-fired power plants across the U.S. They found that building clean energy portfolios – “an optimized combination of wind, solar, storage and demand-side management” – already is cheaper than 90% of those gas plants. Doing so would save customers $29 billion and avoid 100 million tons per year of carbon emissions. If, however, those facilities are built, 70% of them, the analysis found, would be uneconomic to keep running – so-called stranded assets – by 2035.

“There are lots of valid arguments that we need dispatchable generation out in the future, and you can make the argument that a fossil plant is best to do that,” said Teplin. “It’s not always windy or sunny, and current storage works for making up many gaps, but not the long-duration gaps.”

But, he said, as more renewables are built over time, the problem of how to back them up with dispatchable power or storage is a problem that will emerge decades from now, by which point battery technology and other storage options are likely to be far more advanced and achieve economies of scale.

In the meantime, the existing fleet of fossil gas plants is effective back up for years to come. “Our opinion is that the existing fossil fleet in vast majority of places is adequate to charge batteries, and keep things online,” said Teplin. “There may still be a need for dispatchable fossil gas generation in 10 to 20-year time window, but the problem is that gas will only need to be used very rarely. The risk is that they build these big plants but never use them.”

New gas-fired generation simply isn’t needed to keep the lights on, he said.

That hard math makes the reliability case for pipelines like the ACP harder to swallow.

But even as those reports came out, Dominion fell back on its oldest, original narrative for the project. The name of the project in its earliest incarnation –the Southeast Reliability Project – illustrated the core fear that Dominion would use to justify the expenditure, disruption and size of the pipeline. It was the only way to reliably keep the lights on.

Teplin and his RMI colleagues work closely with utilities like Duke Energy. He sympathizes with the twin challenges they face: decarbonize even as they keep power flowing 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. But he takes a dim view of the reluctance of utilities to embrace the mature technology of renewables, in favor of the familiar, but carbon-intensive, path of more gas.

“Do we believe in climate change and acknowledge the costs of that are high? Teplin asks. “If we start from there, then expanded use of fossil gas is simply incompatible with that. The math just does not work. Period. There’s just no way. Yes, it’s cleaner than coal. Maybe half the carbon, maybe quarter if you count all the methane leaks. But we need to be close to zero by 2030. Half is not zero. It’s not even close to zero.”

Each of the legs supporting a case for pipelines – affordability, reliability, “clean” climate-friendly energy – were falling away.

“What we do for a living is change the incentives of our opponents,” said Gerken. The legal roadblocks he and groups like FON had thrown up delayed the project long enough for some new political trends – and some new energy truths – to emerge.

Once they did, the incentives for Dominion and Duke changed dramatically. “Divesting gas is as much a concession to reality as anything else,” said Gerken.

The political, financial and technological landscape had shifted irrevocably since the project was launched in 2014. In a way, Dominion and Duke were the last to notice, or to acknowledge it. “When I stopped and thought about all the factors that drove the cancellation, in some ways it’s more surprising they held on for so long,” said David Pomerantz, executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute, which promotes renewable energy.

“A Larger Sea Change”

A final leg collapsed before Dominion ended its project.

On November 5, 2019, Democrats took control of Virginia’s General Assembly, for the first time in 26 years. Democrats now held a 55-45 margin in the House of Delegates and a 21-19 margin in the state’s Senate.

The next day, I spoke with Aaron Ruby, a spokesman for Dominion Energy. He deflected my question about what that historic shift would mean for Dominion’s fortunes, noting that the company would work constructively with whoever was in control.

Did the push to build the pipeline, in the face of mounting opposition, help trigger that outcome? That’s hard to say, says Lee Francis, deputy director of Virginia League of Conservation Voters. His organization conducted polling during the 2019 campaign, and found that the broad messages of climate action and holding corporate polluters accountable resonated with many voters.

“Anti-Dominion sentiment is pretty high,” said Francis. “The ACP is one example. They’ve been screwing over Virginians for years. The latest estimate is that they’ve over-earned half a billion dollars since 2015. That’s our money.” In August, the State Corporation Commission issued a report concluding that Dominion had charged ratepayers $502 million more than authorized earnings between 2017 and 2019.

“Their overreach has put them into hot water,” said Francis. “More lawmakers are realizing they are a liability and not a friend. There’s a larger sea change that’s happened.”

Clean Virginia, a Charlottesville-based advocacy group launched by the wealthy investment manager and Democratic donor Michael Bills, built a list of candidates who pledged not to take any contributions from Dominion. At last count, 41 members of the House of Delegates have signed the pledge.

“The ACP was a thinly veiled profit grab from day one,” said Cassady Craighill, communications director for Clean Virginia. “That activated a lot of people in Virginia.”

“What’s unique about the ACP is that it represents the most egregious example of utility monopoly over-reach and abuse of the system here in Virginia,” she said. “Dominion and its CEO Tom Farrell manufactured this six-year lie about the pipeline being critical to meeting rising energy demand. That jig was up for a long time. It was hard to convince legislators and landowners, and historic Black communities that this pipeline was necessary for anything other than getting a guaranteed rate of return for Dominion.”

Whether the acrimony and outrage generated by the push to build the pipeline helped flip control of the state legislature – and led straight to the passage of an aggressive climate law – is unclear. But one conclusion seems safe: the campaign to elect a pipeline lost, overwhelmingly.

Virginia citizens voted against a gas-heavy future, and for supporters of climate action and environmental justice. The irony is that Dominion’s failed bet on the pipeline may actually have wound up hastening the end of the natural gas era, in Virginia and beyond.

One key outcome of that fight, Craighill said, was a more energized and educated electorate – and emboldened elected officials. In January, hundreds of citizens marched on the Capitol in Richmond to hold a rally for clean energy, to stop coal and gas infrastructure, and to support fairly wonkish energy reform bills in the legislature.

In March, the Democratic-controlled General Assembly passed the Clean Economy Act. One of its stipulations was that Dominion’s energy portfolio must be 100% clean by 2045. All of its all carbon-emitting power plants must be shuttered by then.

In April, Governor Ralph Northam signed it into law. Almost overnight, Virginia had gone from having no climate target on its books, to having one of the most ambitious in the country.

The daunting math of this 2020 law, the Virginia Clean Economy Act, made the case for the pipeline look even shakier.

“It’s worth remembering that the demand case for the ACP was always patently garbage,” said Pomerantz, of the Energy and Policy Institute. “Dominion was building gas plants so that it could buy the gas from the pipeline it also wanted to build. When the VCEA passed, it showed the emperor had no clothes on once and for all. If they can’t build the gas plants, who exactly is buying the gas? The already flimsy demand case for the gas fell apart entirely with the VCEA.”

And yet, the dream of a long, profitable natural gas bridge dies hard. A month after the VCEA became law, Dominion filed its new long-term 15-year Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). It dramatically boosted planned investment in solar capacity, offshore wind and battery storage assets. It also proposed keeping almost 10,000 megawatts of natural gas-fired generation online through 2045 – in direct contravention of the new law’s requirements – and adding 970 megawatts of new gas-fired generation peaker plants.

Those plants will have to be shuttered within 25 years, long before the age at which most gas power plants are typically retired (45 to 50 years). But ratepayers could keep paying for them – including financing costs and guaranteed returns to Dominion – for years beyond that. The two lawmakers who sponsored the VCEA called it “tantamount to quitting the game before the first pitch is thrown.”

Gerken and Buppert say they intend to use their recently freed-up bandwidth to set a close watch over Dominion’s implementation of the VCEA requirements and hold it accountable to ratepayers.

“We’ll be putting a lot of energy to make sure the things they build are what Virginia and North Carolina want and deserve,” said Gerken. “We have a commitment to hold them accountable. Dominion and Duke just spent six years educating a lot of people about their business. Here in the South, there’s a robust coalition now with a lot of expertise about where the levers of power are.”

Jonathan Mingle, a freelance writer in Vermont, is examining the future of natural gas during his APF fellowship.