The Svalbard archipelago sits halfway between Norway and the North Pole with strategic access in the Barents Sea to vital sea lanes linking Russia, Western Europe and North America. As sea ice vanishes and the Arctic Ocean grows ever more accessible, Svalbard’s geopolitical value has soared. Despite hard economic times, two towns, Longyearbyen and Barentsburg, are struggling to stay on Svalbard, representing a century-old tradition where East meets West with no borders, checkpoints or passports.

Longyearbyen is Norwegian. Barentsburg is Russian. The former has a population of some 2000 that includes over 40 nationalities. The latter claims some 500 citizens, mostly Ukrainian. They are the last two towns on Svalbard’s only inhabited island, Spitsbergen. The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 granted Norway sovereignty over this northern territory as a non-militarized zone while ensuring 14 original signatory nations perpetual commercial rights to the archipelago’s natural resources, primarily coal– the most prized fuel of the time. In 1924, the fledgling Soviet Union joined the pack, having already established, like Norway, mining towns on the main island of Spitsbergen.

While the Svalbard Treaty survived World War II and the ensuing Cold War, it now faces a new challenge. What continental drift and an ancient tropical climate created on Svalbard in the form of abundant coal, modern climate change has undone. Faced with a global climate emergency, nations are weaning themselves of fossil fuels. Coal prices have plunged, driving Svalbard mines toward bankruptcy. In the final days before Norway closed its main mine on Spitsbergen last January, I snowmobiled between Longyearbyen and Barentsburg to see how climate change has impacted Svalbard politics.

Commercial airlines serve Longyearbyen, but travel to Barentsburg is a challenge, especially during the dark, winter-long polar night when the 50-kilometer snowmobile trek is fraught with blizzards and frozen streams. The only guides I could find willing to tackle the route in January came from Barentsburg. Ice and snow drifts forced them to improvise detours, even shoveling a path by headlight down a small, snow-bound waterfall in howling winds and bitter temperatures.

“Russia has recognized its importance of being here, of staying here,” tourism manager Katerina Zwonckova told me in Barentsburg’s only hotel, where I was the solitary guest for two nights. “This is our strategy and we will continue here. We’re not going to leave. If mining doesn’t work, then another thing will: tourism. This is an open way to Murmansk, to Siberia. This is a gateway.”

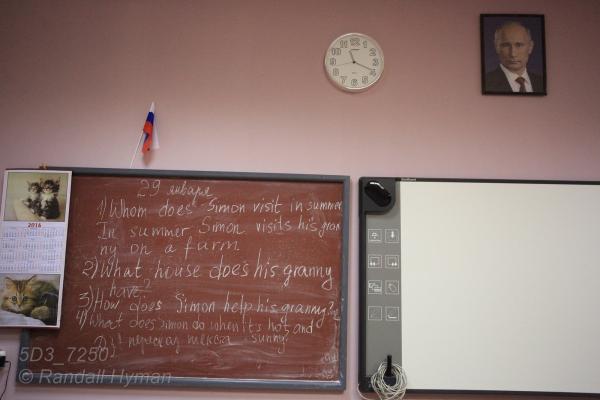

Zwonckova comes from Murmansk, and her attitude reflects Moscow’s efforts to save this hardscrabble Russian town, founded in1931 and still run by the state-subsidized coal company, Trust Arktikugol. In the past two years, Arktikugol has renovated Barentsburg’s largest buildings and removed collapsing ones, but the Soviet-style infrastructure remains indelible. Most residents live in a handful of apartment blocks, and the only restaurants, besides the hotel, are a couple of company cafeterias, closed to tourists. The aging school hosts only primary grades, and the once-gleaming sports facilities are dilapidated.

“In 2013,” Zwonckova added, “it was decided on the governmental level that Trust Arktikugol will change its policy and will try to make tourism priority number one instead of mining. The company’s plan is to make it the main profit. So we have three years to make some kind of brand, to make a special image for Barentsburg and make it different from Longyearbyen.”

If tourism supplants coal in Barentsburg, it will be bitter for Denis Scherba, the mine’s deputy engineer for production and worker safety, who first arrived in 2011. As a third generation miner from Ukraine’s Donetsk region, he is typical of many town residents, who are mostly Ukrainian and vastly outnumber the white-collar Russian citizens. Like Donetsk mines, Barentsburg’s 480-meter-deep, high-sulfur coal mine produces elevated levels of methane gas. Several deadly explosions and fires have occurred over the years.

Trust Arktikugol sits in a large building at one end of town atop the actual mine entrance, where I became the third foreign visitor in its history. Scherba led me down countless concrete stairs through an extensive underground boardwalk. We emerged in a cavernous area lit with amber flood lamps where narrow-gauge tracks snaked across a vast dirt floor. We followed the rails to a checkpoint for trams of coal. A woman named Natalia, bundled in winter work clothes with a woolen cap tucked under a hard hat, monitored the loads. She used a Soviet-era, cast-metal dial phone to communicate inside the mine.

“This is ugol” Natalia said, grabbing a small chunk of coal from the railcar and holding it to the light with a hint of pride. The name “Arktikugol” suddenly made sense to me.

A few days earlier outside Longyearbyen, I had also ventured into the deepest tunnels of Norway’s last working coal mine, Mine 7.

“Yeah, you have to see it before you believe it,” safety inspector Svein Jonny Albrigtsen said as we drove five kilometers underground in a pickup to the depths of the mine. I asked why the walls were white instead of black. “If we suddenly get an explosion from methane, you will probably get a coal dust explosion after that. That’s why we spread out limestone dust, to keep the coal dust from burning.”

At road’s end, we stooped and hiked down loose slopes of rocky dirt guided only by headlamps, occasionally banging against the craggy ceiling. Passing a crossroads of pitch-black tunnels, we finally found a miner hunched against a low seam of coal and permafrost. The earth shook with a deafening thunder as his 60-ton cutting machine chewed away at the coal face. On the hike out, I asked Albrigtsen why anyone would want to spend their waking hours working in the dark amid explosive dust and bone-rattling noise.

“It’s the camaraderie,” Albrigtsen explained. “It’s a real club.”

Longyearbyen started moving away from coal in the late 1980s, when Oslo cut subsidies to the coal company that had run the town since 1916 and stripped it of its autocratic power. Since then, the town has cultivated democratic rule and a burgeoning tourism trade while building a sprawling Arctic research institute hosting dozens of researchers and hundreds of students each year. These support a thriving restaurant scene, cultural events and modern sports facilities year round. Longyearbyen also hosts a Northern Lights observatory and the 31-antennae mountaintop Svalbard Satellite Station, the only ground facility outside Antarctica capable of tracking all 14 orbits of polar satellites.

Longyearbyen may have a head start in surviving the decline of coal, but Russian towns like Barentsburg once dominated Spitsbergen. At the height of the Cold War in 1960, Svalbard’s Russian population topped 2600, far outnumbering Norwegians there on their own soil. The 1985 Norwegian movie, Orion’s Belt, based on the fictional discovery of a radio spy station on Spitsbergen, mirrored widespread distrust of Soviet presence. By 1991, when the Soviet Union fell, Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Fyodorov said Russia no longer had any interest in remaining in Svalbard. An airplane crash in 1996 that killed all 141, mostly miners and their families, led to the abandonment of the last major Russian mining town besides Barentsburg.

Since then, Moscow has asserted renewed interest in Svalbard and beyond, making geopolitical waves in the Barents Sea. In April 2016, Russian trainers and dog teams stopped over at Longyearbyen’s airport on their way to military exercises near the North Pole, despite objections from Oslo that their transit violated the non-military provisions of the Svalbard Treaty. A year earlier, mainland military exercises simulated an invasion of Scandinavia, as described by a Washington think tank and reported in The Telegraph. Months later, famed Norwegian crime writer Jo Nesbø’s television series, Occupied, dramatized a Russian invasion of Norway, premiering to record-breaking viewership. Moscow reacted angrily, calling it “in the worst traditions of the Cold War.”

“The 1990s weren’t the best time for the Soviet Union,” Zwonckova told me when I asked about living under Norwegian rule on Svalbard. “It was a very weakened partner, and that weakness was taken into consideration by the Norwegian side. They felt that they could influence more freely, they felt their strength. But right now the situation is a bit different.”

SIDEBAR: The specific terms of the Svalbard Treaty have long fostered disagreement between Norway and Russia over marine resources, especially fisheries. Traveling with the Norwegian Coast Guard in 2013, I visited a Russian trawler in Svalbard waters with Norwegian fisheries inspectors. After a long day of examining nets, trawling procedures and fish catch, the Norwegian officer presented the trawler captain with inspection papers. He refused to sign. I later learned that all such inspections have concluded this way for decades. The Svalbard Treaty was written when territorial waters only extended four nautical miles from shore, but maritime economic zones are now 200 nautical miles worldwide. Moscow insists that only the original terms of the Treaty apply.

###

“A version of this story appeared in Foreign Affairs.”