“While waiting for an officer to handcuff and escort me back to the cell that awaited me after showering, I sat on the floor holding a razor used for shaving,” W writes to me. “Today was the day I decided to end my life.”

I do not know W. I have never met him. I have no idea whether he is black or white, tall or short, old or young. I don’t know what he’s done that’s landed him in prison, or why the prison system has seen fit to place him in solitary confinement.

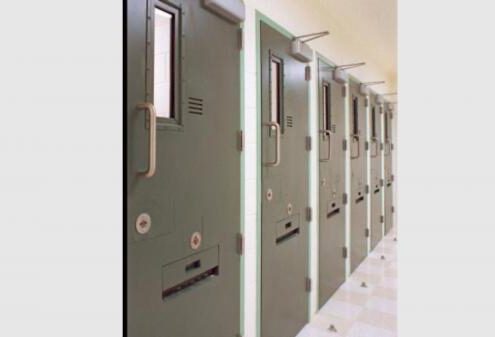

Every week I receive 50 or so letters from people like W. He is one of 80,000 men, women, and children who live in states of extreme isolation in U.S. prisons and jails. They spend their days and nights in cells that measure, on average, 6 by 9 feet. They live sealed off from the world, sometimes without a window, usually behind a solid metal door with a slot where a guard can slip in a food tray. If they are lucky they are let out a couple of times a week to shower, or to exercise for an hour in a fenced or walled pen resembling a dog kennel.

There is no education in these solitary confinement cells. No work. The people who are held there may or may not be allowed reading materials, or a set of headphones to plug into a wall jack with a few radio stations. They are rarely permitted to make phone calls, or have visitors. Some are allowed to have family photographs, but usually only a limited number—so if a new one comes in, they have to decide which one to give up. Most are forbidden to hang the photographs on their walls.

If they are ever taken out of their cells, they are flanked by guards, wrists and ankles cuffed and shackled to a black box at their waists. They may have trouble walking, not only because of the shackles but because it’s been quite some time since they were able to take more than a few steps in any one direction. They will probably have trouble seeing, as well, since they’ve had no use for their long-distance vision.

They are escorted down the tier amidst a din of screaming prisoners—some with underlying mental illness, others driven mad by “the box”—who cut themselves, pelt their own cell walls and the corridor with piss and shit and blood. At night the screaming continues, sometimes turning into the sounds of a barking dog, dying down to where you can only hear the sobbing, the voices begging for their mothers, for the sight of a child last seen ten years ago—and frequently, begging to die.

This is what they tell me in their letters—the letters that at first trickled in every once in a while, when I first began writing about solitary confinement, and now come by the dozens. People in solitary sometimes manage to communicate by shouting, by tapping on pipes, and by “fishing”—passing things along lines constructed from sheet threads and skimmed across the corridor floor, from the crack under one cell door to another. Some, it appears, have shared my address, and the fact that I am interested in knowing what life in solitary confinement is like.

I am a journalist. I’ve been taught to report what I see and hear and know, and nothing else. These letters should be nothing more to me than documentary material—and perhaps not even that, since the conventional wisdom is that prisoners’ accounts can’t be trusted. No need, really, to write back, even though that’s what my correspondents are clearly hoping for.

“Mail is manna from heaven,” R writes me. “When I hear the squeak, squeal and rumble of the mail-cart being pushed down the gallery, I start saying to myself, “You’re not getting any mail, so don’t even expect it. Nobody knows you anymore. No one wrote, so stop it!” Then, as the cart squeaks and squeals and rumbles a bit louder as it gets closer, I’ll jump off the cot and start pacing. Then I’ll squat in front of one of my spiders (the SHU Prisoner’s Loyal Pet) and I’ll start talking to it (you talk to your pets, too, don’t you?!) I’ll say, “Come on! Hope with me that we get a piece of mail. Come on! If you hope with me then we’re guaranteed a letter,” and I’ll do a little fist pump…”

So I write back with a few bits of news, a few lines of encouragement. I write half a page to B, who has been in solitary for more than 25 years. He writes back 20 pages, telling me the story of a mouse he had begun feeding in his cell. The mouse’s back legs were injured, so he’d built it a little chariot out of Styrofoam and bits of cloth. The mouse had learned to get around with on his makeshift wheels when a corrections officer discovered it and stabbed it to death with a pen. “I had three dogs that I loved when I was growing up, and I loved Mouse every bit as much as I had loved them,” B writes. “For the months he had been with me he had been good company in a place that can be a lonely world, and I would miss him dearly.”

B wants nothing more than to share his thoughts, to know that there is another human being, somewhere in the world, who is interested enough to read them. Others want things. G wants me to look up a long-ago high school girlfriend. He hasn’t heard from her in 25 years and doesn’t know where she lives. He wants her address so he can write to her. I know I can’t send it to him, so I don’t even look.

D manages to write to me in spite of that fact that, like about a third of the people in solitary, he suffers from severe mental illness. After a while he asks for a sex magazine, even though receiving one could get him in deep trouble. When I refuse, he asks for—and I send—some Spiderman comic books. Next he asks for a Bible. He seems to sound less suicidal than usual, so I quickly send that as well. D writes me that it never arrived, so I track the package on Amazon, which says the Bible was delivered to the prison. Apparently someone stole it. Then D asks if I can put his name on my website so “I can have penpals…and maybe find that special someone.”

J writes on behalf of another person he met in prison: “During my stay at the mental health unit, I came to know a man named G. Mr. G was clearly not a quick thinker and had mental health issues. On one occasion an emotionally unstable corrections officer opened G’s cell and slapped him across the face because he had taken too long in giving the officer back a food tray after a meal. In another example, involving these two, I witnessed the corrections officer direct a nurse not to give G his mental health medication because G could not decide in a timely manner if he wanted to take the medicine or not…These two incidents happened in a mental health area reserved for suicidal prisoners.”

I know that thousands of people in solitary are like G—too ill, or not literate enough, to write at all. They are completely cut off, trapped in their own minds as well as in their cells. But I have a hard enough time dealing with the people who write to me, and try hard not to think about the people who are not writing.

Y reports: “I’ve witnessed officers…encourage a mentally ill prisoner who had smeared feces all over his control cell window, to lick it off, and they would give him some milk. And this prisoner licked most of the fecal matter off of the window, and was ‘rewarded’ by the officer who threw an old milk to the prisoner through a lower trap door to the cell.”

Along with the tirades about certain guards there are copies of painfully hand-printed legal documents, full of “whereas” and citations of this or that federal court case, written in the hope that some judge will read it and get the author out of solitary. But the judges, with few exceptions, have ruled that solitary confinement is not cruel and unusual punishment. Not even for the man who drilled a hole in his head to try and stop the pain.

There are so many letters now that I cannot possibly reply to most of them, even with a couple of volunteers to help. So I buy packages of cards, and gather up all the ones sent to me for free by wildlife groups as thank-you gifts for donations. I start sending people in solitary pictures of polar bears and endangered gray wolves, with just a few handwritten words: “Thanks for your letter. Stay strong.” They write back with a level of gratitude totally disproportionate to my lame missives.

A man writes me about the sound of rain in a drainpipe. It is his weather report. Another writes about the parade of cockroaches down the corridor at night, which he watches through the slot in his door, desperate for any sign of another living thing. Still another writes to thank me for the smell of perfume that he detected on an envelope containing a card. The smell lingers in his cell, he says, and fills him with dreams of the outside world.

Some people manage to pick up information about what is going on in that outside world. They write to ask for more news about the hearing on solitary confinement held in Congress, about whether things are changing. I can’t bear to tell them that it may be years or decades before anything changes for them—though some already know it. “I heard the head of the Bureau of Prisons in Congress (on radio) saying they do not have insane inmates housed here,” writes J, who has spent a decade in the federal supermax prison. “I have not slept in weeks due to these non-existing inmates beating on the walls and hollering all night. And the most ‘non-insane’ smearing feces in their cells.”

Some of these people have done very bad things in their lives. Others not so much. People get sent to solitary in the United States for a panoply of absurd reasons—having too many postage stamps, smoking a cigarette, refusing to cut their hair. But after reading these letters, I can’t accept that even the worst of them deserve to live this way.

J, who is in solitary for trying to escape, remains defiant. “I refuse to embrace the solitude. This is not normal. I’m not a monster and do not deserve to live in a concrete box. I am a man who has made mistakes, true. But I do not deserve to spend the rest of my life locked in a cage–what purpose does that serve? Why even waste the money to feed me? If I’m a monster who must live alone in a cage why not just kill me?”

I know that some people, in fact, do prefer to die rather than live this way. In barren cells, they become ingenious at finding ways to kill themselves. They jump head-first off of their bunks.

They bite through the veins in their arms. About five percent of all American prisoners are in solitary confinement, but half the prison suicides take place there.

The rest find ways to keep going. What keeps D alive is his mother. For B, it’s his writing. For J, it’s the small window in his cell. “Every now and then a pair of owls roosts on the security lights,” he writes. “This spring they had two babies. We watched them grow up and fly away. On any given day the sky here is breathtaking. The beauty out my window stays in my mind. I look around this cage at plain concrete walls and steel bars and a steel door, a steel toilet and I endure its harshness because I am able to keep beauty in my mind.”

Sometimes, now, I spend entire days reading letters from these people, these criminals, these models of human fortitude. I can’t do much of anything for them, except keep on reading.

A second letter comes from W. “I want to apologize to you for my previous letter,” he writes. It must have been very uncomfortable for you to read that letter. It was extremely wrong for me to express such a personal issue to people I don’t know. But my lack of interacting with people on the outside sometimes causes me to come out and express things that I probably shouldn’t. So I hope you can somehow empathize with my situation and forgive me for the context of my previous letter.”

W is alive.

James Ridgeway, a Washington, D.C. freelancer, is writing about the criminal justice system and modern-day banishment.