This Mom Checked Her Newborn Out of the Hospital Early. The Next Day Her Baby Was Taken Away.

Tiffany Langwell was thrilled to find out she was pregnant again at the age of 38. She had two children from her first marriage — a 15-year-old girl and a 9-year-old boy. After separating from their father, she had reconnected with a high school boyfriend, David Hodek, and they had gotten engaged. In August of this year, their baby girl was born healthy, at 8 pounds, with bright blue eyes and a full head of downy hair. Langwell and Hodek had what they describe as a blissful first night home.

The next day, a representative of the child welfare agency in Riverside County, California, took the infant into protective custody.

Unhappy stories about child welfare agencies typically focus on instances of their failure to protect a child from harm at the hands of its parents, as in the recent Colton Turner case in Texas, in which three Child Protective Services (CPS) workers were fired after a boy left in his mother’s care died. These stories raise the question of why more wasn’t done to prevent such tragedies. What we don’t hear about as often are the cases in which parents and their lawyers say social workers have done too much.

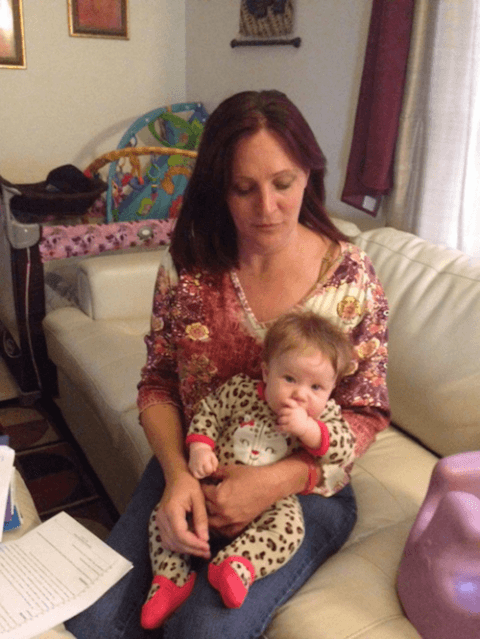

Langwell recently moved into a new house, across the street from her mother. It’s a one-story, three-bedroom house in the Palm Springs region, surrounded by palm trees and breathtaking hills. She has a gap between her front teeth, dark red, shoulder-length hair, and she wears jeans and a stretchy shirt over her athletic frame. While nursing her baby, Langwell sits on her couch, surrounded by a bassinet, ExerSaucer, and Pack ‘n Play. She describes her daughter’s first week as a living nightmare.

Langwell had been having contractions for two days when she told her fiancé at 11:30 p.m. that it was time to head to Desert Regional Medical Center, which she’d chosen because it allowed rooming-in and she didn’t want the baby to leave her side. Once there, she asked for an epidural, but by the time everything was in place for her to receive one, it was too late. She delivered the baby naturally at 2:34 a.m., and around noon was put in a room with two other new mothers and their babies, including one who Langwell says kept talking loudly on her cellphone.

Later that afternoon, Langwell decided to check out and go home. Langwell said the baby was breastfeeding well and was healthy, and she preferred to take her home early “AMA” (against medical advice) so they could all get some sleep. When she left, a member of the hospital’s staff called and reported her to the county’s child welfare agency.

“Desert Regional Medical Center takes very seriously its commitment to the health of mothers and infants in our care,” Richard A. Ramhoff, the hospital’s marketing director, told Cosmopolitan.com, after saying that the hospital could not comment specifically on Langwell’s case. “As mandated by state law, the hospital calls the County of Riverside Department of Public Social Services hotline when staff believe the situation warrants a referral. This reporting is not done lightly. Our staff reviews the details of each situation individually before fulfilling our responsibility to refer a case to child protective services for further review.”

According to the child welfare agency’s report, a hospital staff member described Langwell as “hostile” and suggested that her behavior was “consistent with someone with substance abuse issues.” (According to a representative from the county’s child welfare department, the majority of the cases they see are neglect cases, and most of those are related to substance abuse.) The staff member said the couple and Hodek’s mother seemed shaky and had rapid jaw movement, and that Langwell put two pill bottles in her bag. Langwell says the only pills she had in her bag were her iron supplements. She says she was severely sleep-deprived from her two days in labor and upset that she never got her epidural, and that her fiancé and his mother can be abrasive and were also exhausted, but beyond that, she doesn’t know what about the trio’s behavior could have sent up a red flag. “I never cussed anyone out or anything,” she says.

A child welfare agent came to the house the next day to check on the baby. The home had a security fence, and Langwell and Hodek did not hear the knocking at the gate, which was some distance from the front of the house. The agent called the police. When Langwell eventually appeared at the security gate, she saw two police officers and the welfare agent, who told her that the hospital had alerted the agency when she checked out early. Langwell refused to let the police and welfare agent inside the house but brought the baby out so they could see that she was OK. The agent noted in her report that the baby had good coloring. Langwell submitted to an on-the-spot drug test, but according to the report, the test was inconclusive, because her saliva sample was too thick — “which may have had something to do with the fact that I had just given birth and it was 110 degrees,” Langwell says bitterly.

The agent returned later that day with a warrant to take the baby — just to the hospital for a full exam, Langwell and Hodek initially thought. Langwell insisted on riding along in the car with the baby. Hodek and his mother followed behind. Hodek says hospital workers then attempted to catheterize the baby to procure a urine sample for a drug test. “I’ve worked as a medic and seen a lot of terrible things, but this I can hardly even talk about,” Hodek says. “They tried eight times to catheterize my one-day-old baby.” Hodek’s mother covered her own head with a blanket to try to block out the baby’s screaming. The hospital couldn’t comment on particulars of Langwell’s case, but according to the welfare report, “The hospital was unable to secure a urine sample from the infant.”

Langwell and Hodek thought at that point that the baby was coming home with them, but the caseworker said the baby was being placed into protective foster care. Langwell, who now understood they thought she was on drugs, says she fell to her knees in the hospital. “Drug test me right now!” she said. “I can prove I’m not on drugs!” According to the agent’s report, Hodek, who is 6-foot-4, seemed to be under the influence and became “hostile.” He denies the first charge, but not the second. “Was I hostile?” he says. “Sure. They were taking my baby girl.”

Langwell describes the seven days that followed as the worst of her life. “They took my baby from me. I sat there for a week and just cried,” she says. “Some days I didn’t get dressed. I didn’t eat. I made myself eat one meal a day to keep up my strength and to keep my milk supply up.” She and Hodek stayed in constant touch with the agency, trying to get the baby back, and attended a hearing at which she learned that the court had appointed separate lawyers for Langwell and her baby. She pumped regularly, and the caseworker picked up the milk. Langwell says she thought, “If she can’t have my arms, she can have my milk.” But according to the report, her caseworker told her that the milk would be kept frozen until the mother produced a negative drug test.

Langwell’s mother, Jean Cinq-Mars, says that week was “heartbreaking” and describes her daughter as “a wonderful mom.” When her two older children came home from a vacation with their father, they were confused about why the baby wasn’t there. “We were running through the house looking for her,” says Langwell’s teenage daughter. Langwell’s son reports that he was “really mad that they took [his] sister.” Both say they are fond of Hodek and excited about the new baby. After a few days, Langwell says, “It was almost like being pregnant and giving birth had been a dream, like it wasn’t real.”

Sara Ainsworth, the director of legal advocacy for the group National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW), says Langwell’s story is an example of how the behavior of new mothers, especially poor ones, and especially those of whom drug use is suspected, can come under intense scrutiny. In a 2011 statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists wrote, “A disturbing trend in legal actions and policies is the criminalization of substance abuse during pregnancy.” Ainsworth says Langwell’s story is also an especially vivid example of how traumatic CPS involvement can be to a new mother.

“We often see the extremely problematic ‘If you test positive for a drug, we’re going to take the baby’ cases,” Ainsworth says, “but this is a next step: ‘If we think you used a drug because of your poverty or your conduct, then we’re going to step in.'” As described in a recent New York Times op-ed, NAPW has documented hundreds of cases in which pregnant women have been charged with crimes based on the rationale that “fertilized eggs, embryos and fetuses are persons or at least have separate rights that must be protected by the state.” In July, Tennessee began enforcing a new law under which women can be prosecuted for assault if they use drugs during pregnancy. Since December 2013, Alabama has formally accepted the judicial interpretation of the word “child” in its child abuse law to also mean “fetus.” As a result, in that state, there have been some 130 arrests of pregnant women and new mothers in the past 12 months.

New mothers suspected of drug use do not face criminal justice or child welfare involvement only in conservative Southern states. In September, the New Jersey Supreme Court in Trenton heard the case of Y.N., a new mother who was charged with child abuse when it was found that she had taken oxycodone and methadone during her pregnancy. “You have laws in conservative states that you’re not going to see pass in more liberal ones,” says Ainsworth, “but child welfare is operating under the radar.” Ainsworth says there are no good numbers, but that anecdotally, NAPW has seen a surge in both criminal prosecution and child welfare involvement for new mothers.

While arrest is generally considered a more extreme response, child removal can prove at least as upsetting to a family. According to the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, cases like Langwell’s are not uncommon. According to one of the group’s position papers, “Contrary to the common stereotype, most parents who lose their children to foster care are neither brutally abusive nor hopelessly addicted. Far more common are cases in which a family’s poverty has been confused with child ‘neglect.'” The group’s rough estimate is that half the children in foster care on any given day could be safely in their own homes if the right kind of help were available to their families.

During that first week of her baby’s life, in the course of the phone calls and appointments with the caseworker, Langwell was given a criminal background check and a hair follicle drug test (which can determine if someone has used any drugs in the prior 30 to 90 days). Eventually, there was another court date and Langwell’s baby was returned to her. Langwell never met the foster mother with whom the baby spent her first week. “They just handed us back the baby by the parking lot,” says Cinq-Mars, Langwell’s mother. “‘Here’s your baby,’ like, ‘Here’s that thing you ordered.'”

“It’s legalized kidnapping,” Langwell says. “I thought it was some horrible joke. You are guilty until you prove your innocence. Who cares that they slandered my name? But they took my daughter for the first week of her life and put her with a stranger.” Ironically, among the paperwork Langwell has received from the court are several pages about baby care that included a section titled “Bonding.” The paperwork also includes a mention of Langwell’s hair follicle drug test results: negative.

“Getting her back was the happiest thing,” Langwell says, “but sad too, because her dad had to move out.” (According to the caseworker’s report, Langwell said Hodek lives in Los Angeles, but she says the caseworker misunderstood her.) The agency has yet to complete its investigation of the baby’s father, who revealed to investigators that he takes prescription medication for his work injury and for anxiety. When the caseworker asked about his criminal history, Hodek admitted to a petty theft conviction. Court documents in the child welfare case list several additional arrests from his past. He now lives in a motel and is allowed to see the baby twice a week for an hour at a time, in a CPS meeting room. In the meantime, he scrolls through photos of his daughter on his phone and makes an effort to comply with CPS’s directives, which include going to therapy and getting new prescriptions for his medication. (He says the pills he has now were prescribed two years ago.) “When you’re dangling someone’s child on the end of the hook, you’ll do or say anything,” Hodek says. “‘I stole the Lindberg baby! I was on the grassy knoll! Now can I see my baby? Every day that goes by I’m missing more firsts.” Langwell says she’s been told Hodek may be permitted to move back home this spring if he complies with all the agency’s requirements.

Now at home with her mother, sister, and brother, the baby, who is calm and smiley, is already sitting up in her purple Bumbo chair, ignoring Baby Einstein videos to gaze at her mother’s face, and laughing in the car seat when her siblings tickle her feet. Cramming groceries into her already-stuffed freezer, Langwell says, “You know what’s funny? They [the welfare agency] were here two weeks ago for a house check and said they needed to make sure there was enough food for 24 hours. I said, ‘I shop at Costco. I can barely fit anything else in my fridge. I have two weeks’ worth of barbecue sauce alone.’ They also made me undress the baby all the way to show that she didn’t have any bruises. I said, ‘Couldn’t you have thought of that a few minutes ago when I was changing her diaper?'” She doesn’t know how much longer the monthly checks will last.

When I approached the child welfare agent who made the removal in Langwell’s case at the Riverside County office, she said that confidentiality regulations prohibited her from discussing specific cases, but Jennie Pettet, assistant director of the Riverside County Department of Public Social Services, Children’s Services Division, did speak to Cosmopolitan.com about the county’s child removal process.

“The Juvenile Court upholds approximately 98 percent of our actions to remove children from their homes based on evidence presented,” Pettet says, meaning that in about 2 percent of the cases where a removal has occurred, the judge will return the child to the home of a parent. She explained that “a lot goes into the decision to remove,” including the social worker’s risk and safety assessment, consultation with a supervisor, and — in cases like Langwell’s, where a warrant is needed — a judge’s sign-off. According to Pettet, there is a “global assessment,” and no single issue — drug use, leaving the hospital early — would be considered in and of itself sufficient to warrant removal. “We work closely with families to prevent removal of a child whenever possible,” she says.

And yet, Ainsworth of NAPW says Langwell’s case is emblematic of something she sees happening with increasing frequency around the country. “Women — even women in more politically liberal states like California and even women who have broken no laws — can find themselves trapped in this kind of nightmare scenario,” Ainsworth says. “This really could happen to you, and it’s really unfair even if it doesn’t happen to you.”

###

Ada Calhoun is a 2014 Alicia Patterson fellow. Follow Ada on Twitter.

© 2014 Ada Calhoun