ARUA, Uganda — Isaac Baniyo stumbled through his final exam in English last November as a pounding headache and chest pain made it difficult to focus.

The teenager’s parents sent him on foot to a drug shop not far from their grass-roofed hut in the village of Wali, but the tablets he brought back in a folded sheet of paper failed to clear his symptoms. His fever soared, his breathing became labored and he hacked up bloody mucus.

The dead rats in the village should have been a warning sign: Baniyo had caught pneumonic plague, the contagious form of the disease responsible for history’s most notorious epidemics, including Black Death of the 14th century.

Far from being consigned to the Middle Ages, between 1000 and 2000 plague cases are reported to the World Health Organization each year. Plague has spread, via humanity and its rats, to the burrows of prairie dogs in the American Southwest and up the Nile River to remote corners of Africa. The world’s deadliest plague zone is centered here on the restive border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where a scrub-covered plateau provides the optimal climate for plague-carrying fleas and plague kills one-third of those it infects.

But as part of a clinical trial sponsored by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, health workers treated Baniyo, and he made a full recovery. Although he failed his school exam, at least he has a chance to repeat the year. Another girl in Wali was not so lucky: She became one of six who died here in 2012. Forty-nine others were treated as a precaution, and a potential outbreak averted.

For the last decade, identifying and stopping plague has become the unlikely goal of a far-flung team of 30 researchers sponsored by the CDC, who are developing better diagnostics and treatments and collaborating with traditional healers in an effort to reduce plague deaths. It’s more than a humanitarian mission, but a bulwark to prevent this age-old pestilence from crossing the globe in an airplane, or, worse, becoming a modern-day biological weapon. “We’re not going to completely eliminate plague,” says epidemiologist Paul Mead of CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases in Fort Collins, Colo., “but if we can put out the fire early on, we can reduce the deaths and economic impact.”

Infected Fleas

The plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, typically makes the leap to humans as infected rats die, forcing fleas to find a new host. The best-known form of the disease, bubonic plague, results in painful, golf-ball-size swellings, known as buboes, in the lymph nodes of the groin or armpit. Plague can also cause hemorrhaging of blood vessels in the fingers and nose, leading to dark-purplish gangrene — hence the name “Black Death.” If bacteria reach the lungs, the pneumonic form of plague can spread from person to person through coughing. Untreated, plague is almost always fatal within a week, but identified within the first 24 to 48 hours, it can usually be cured with antibiotics.

Because the United States has an average of just five plague infections each year, CDC researchers decided in 2003 to conduct their research on predicting and preventing outbreaks abroad. They focused on Uganda. In the decade since, they have identified 1,287 suspected plague cases.

Typically, the only way to definitively diagnose bubonic plague was to insert a hypodermic needle directly into a bubo, inject a solution and withdraw the fluid. The sample was then cultured, stained and put on a slide. Under a microscope, Yersinia pestis looks like a safety pin — an oval with caps on either end. Prior to the CDC’s involvement, most clinics in Uganda didn’t have microscopes, nor the expertise to use them, much less an adequate supply of sterile needles and solution.

But after years of testing in Uganda, the CDC is finishing a study of a low-cost dipstick, not unlike a home pregnancy test, which requires just a drop of blood or urine to reveal within minutes if a person has plague. Jeff Borchert, the CDC scientist who oversees the project in Uganda, says that having such a test would be critical in the event of a biological attack and that the United States could provide free tests to Uganda and other plague-endemic countries.

Meanwhile, the researchers have sought to expand drug options, because some intravenous antibiotics, such as streptomycin, are not widely available and because drug resistance to other antibiotics poses a concern. The go-to pill for an anthrax attack is ciprofloxacin, which is part of the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile established for national emergencies. The researchers hope it will also be approved by the FDA for plague.

As part of the ongoing clinical trials, 14-year-old Isaac Baniyo’s plague was diagnosed with a dipstick; he then became the fifth plague patient — and the first with the pneumonic form of the disease — treated with a 10-day dose of cipro. Fortunately, the drug worked for him. “It’s a very big step forward,” says Tom Ingelsby, director of the Center for Biosecurity of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not involved in the research.

A role for traditional healers

Despite their efforts so far in Uganda, the team has not achieved its goal of reducing plague mortality from about 30 percent to 15 percent. Mead at first suspected that people farthest from clinics were not getting diagnosis and treatment within the two-day window that makes the difference. That hunch proved wrong.

It turned out that cultural traditions were key, and they were working against the CDC. Many people in Baniyo’s village rely on traditional healers, who treat illness with herbs or prayers. During a 2008 outbreak of pneumonic plague, the healer was one of those sickened — and a fully stocked clinic was less than a half-mile away. “Having a diagnostic dipstick and effective antibiotics doesn’t really matter if a person doesn’t get to the clinic,” Mead says.

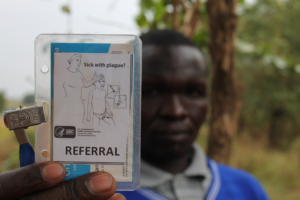

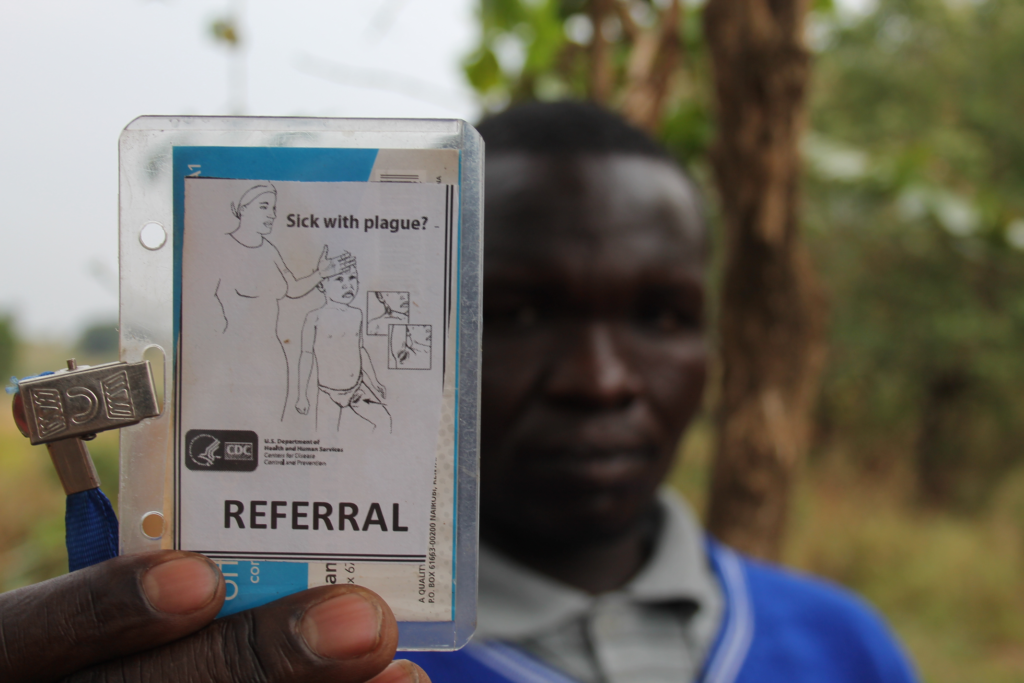

So in 2010, Titus Apangu of the Ugandan Virus Research Institute, with funding from the CDC, began recruiting 10 of these traditional healers, training them to recognize plague symptoms and providing them with bicycles, cellphones and referral cards to direct patients to a specialist at the local clinic. The number of healers working with the institute has now climbed to 42, and they have made 562 referrals for suspected cases of plague, malaria, tuberculosis and other serious illnesses. Some are even sporting homemade uniforms with a CDC logo.

On a recent morning, Mark Wadribo, a healer in a blue sweater with a wooden cross around his neck, pulled out his book of referrals and told the story of a young farmer who limped into his compound last year. The man was so weak, he could barely speak. “When I examined him, I found high fever,” Wadribo recalled. “I asked if he had swellings.” The man revealed a bubo on the left side of his groin.

In the past, Wadribo treated such patients by making incisions and rubbing herbs in the wound. This time, he grabbed his cellphone and told his brother to ready the motorbike. They had a plague to stop.

A version of this article appeared in the Washington Post.