She looked like a human crucifix — arms outstretched, left hand grabbing the wall while the right hand grasped the door, legs clamped. Maria Guadelupe Aranda was in labor.

I didn’t know Lupe when I put my hands on her belly. I didn’t even speak her language. But when a contraction hit, she stopped in front of me, took my hands and showed me how to massage her pains. The folds of her stomach rolled like gelatin between my fingers, and I could feel the coarseness of her private hair. As the pain lingered, she squatted on the floor, spread her legs with her toes turned under her feet, and quietly groaned as she pushed.

At twenty-six and bearing her seventh child, Lupe had walked into the Holy Family Birth Center in Weslaco, Texas, alone. She carried no satchels filled with clothes, no diapers, no video camera. She arrived on that cool October night with only the donated clothes she wore: a maternity shirt, pants and scuffed white tennis shoes.The nuns who run the birth center know Lupe well; she had birthed two other babies here, and even named her last child after Sister Angela Murdaugh, the center’s founder and nurse-midwife who delivered Lupe’s last daughter, barely two years ago. Lupe and Sister Angela developed a friendship with Lupe nicknaming the heavy-set Sister Angela “Gordita,” meaning “fatty.”

I had come to the birth center for the second time to watch the sisters deliver babies, to further witness their work with the undocumented women in South Texas. I didn’t expect that the story of Holy Family would be just as much about the women on the birthing beds as the hands that delivered their children and eased their poverty. And I never expected to learn so much about the sacrifice of birth.

When the sisters suggested I stand in as support for Lupe, they nodded to each other with a quiet acknowledgment. They knew what they were asking of me, but I did not. Lupe’s labor was expected to be long and arduous. She was anemic and had bled dangerously during her previous births. Her first baby miscarried at seven months. She carried her second child to term when she was 17 years old. Each delivery after that proved increasingly difficult. The older midwives knew what was happening: Lupe’s uterus was tired and giving up.

Lupe was the same age as the young, smooth-skinned, unmarried volunteers at the clinic, but she didn’t readily trust them. Sister Angela had never carried a child of her own, but she had delivered more than 1,500 babies in her 28 years as a midwife. Lupe trusted that kind of experience.

Sister Angela is a large, handsome woman. Like an older Rosie O’Donnell, she is a Catholic woman who is rarely seen without a smile and a laugh. Her bright blue eyes and freckles make her look younger than her 58 years. Her hair is short, curly and blond and is graying at the temples. Her front teeth are slightly bucktoothed and she speaks in a twangy Southern drawl. She’s most comfortable in baggy, casual clothes and detests “getting all gussied up”— a cross she has to bear frequently in her position.

But Sister Angela was not the midwife on duty the night Lupe came in. It was Kamala Krakover, a 33-year-old volunteer nurse-midwife who arrived in August fresh from midwifery studies at New York University. Immediately, Lupe voiced her reluctance and repeatedly asked that Sister Angela deliver her baby.

“In their culture, they really trust their elders,” Sister Angela explained. “Kamala looks like she’s 14.”

Kamala has a dark, exotic look. Her face is long and gaunt, but her eyes sparkle like blue marbles. Her voice, though, is that of a child — breathy and high-pitched.

Right away, Kamala knew she needed to gain Lupe’s confidence. When Lupe arrived that evening at 6 p.m. claiming she was in labor, Kamala could find no physical sign that would confirm what Lupe was saying. She wasn’t dilated, and her cervix wasn’t open. But Lupe insisted Kamala admit her anyway.

Two hours later, in the “Mary” birthing room, Lupe had dilated to six centimeters and was having regular contractions. Kamala was amazed that Lupe knew her body so well that she could feel the onset of labor before it happened.

Lupe sauntered around with bare feet in a light blue cotton hospital gown. As she paced from the birth room to the adjacent bedroom and bathroom, she spoke in Spanish and broken English. The walking reminded her of her exodus from Guatemala six years earlier when she rode a bus for four days and four nights before she arrived at the Mexico- Texas border, she said, holding up four fingers to emphasis the duration of that journey. To reach her family in Progresso — a town on the Texas side of the border, Lupe swam the black waters of the Rio Grande underneath the border’s barbed wire by the cover of night.

Lupe had to leave behind her two little girls, Sedy Linette, now 8, and Claudia Carolina, now 9. Though Lupe is Mexican, her daughters were born in Guatemala and couldn’t leave without proper government papers. Lupe was too distraught to wait the months or years that might take: She had discovered that her common-law husband was having an affair. He had begged her not to leave, and promised to take good care of her. She was too hurt to stay.

Guatemala was not her home. Lupe was born in Mexico and lived in Cruzeros de Flores, near the Texas border. She was eight years old when her family moved to Texas via inner tubes along the river the Americans call the Rio Grande and the Mexicans call the Rio Bravo. She met her husband when she was just 14 years old. The two wanted to marry, but her parents were opposed. They ran off to Guatemala where they lived with his parents in the outskirts of Guatemala City.

Lupe says her husband’s parents did not accept her. It wasn’t long before she became pregnant. She lost the child she believes because she wasn’t able to get enough nutritious food. Within the next couple of years, Lupe’s situation improved. Her husband bought a house, and Lupe gave birth to two daughters.

When she left Guatemala, Lupe placed the girls with their Madrina or godmother. Her husband gave her money to return to her parent’s home. A few years later, though, he came to Texas and begged Lupe to come back to him. It was during his visit that Lupe became pregnant with her fourth child. After the birth of Juan, Lupe met another man who fathered her son Rene and daughter Angelica. But that man was also unfaithful to her. Now she was pregnant with her seventh child by a third man who also had left her.

In between contractions, Lupe asked me if I had children. I told her I had two, a 13-year-old son and an 11-year-old daughter. Lupe’s eyes lit up and her lips formed a half-moon smile. She seemed to take comfort that she was delivering her baby with another mother.

“Then, you know what it’s like,” Lupe said through Kamala.

I shook my head. “My children are adopted,” I said. “I’ve never given birth.”

Lupe’s smile faded a little. But then she patted my arm, as if to give comfort. “It’s okay,” she said in English and then she asked me in Spanish: “You want to have babies?”

Just then a contraction hit and Lupe doubled over and grabbed her stomach.

After a couple of contractions, Lupe pushed away Kamala’s hand and reached for mine.

“She says you have bigger hands and can rub harder,” Kamala said, smiling.

I grinned back. For the first time since I’d entered the birthing room, I felt I was needed. I was supposed to be Lupe’s physical and emotional support, yet I couldn’t even speak directly to her. I hadn’t ever given birth so even relating to me as mother was limited. Yet, I sensed that Lupe liked my being there if only because of my big hands. But I believed it was more than that. Lupe knew she was teaching me.

Lupe said she wanted a girl this time so she would have two boys and two girls at home. She was eager to hear what I thought she might be carrying. She moved my hands around her belly, and then asked me what I felt. I said it felt like a boy.

“I hope you are wrong,” she said in Spanish, smiling.

Before midnight, Sister Angela stopped by to see Lupe and to praise Kamala as a skilled midwife. Lupe was taking a hot shower, trying to ease her contractions. Sister Angela sat on the edge of the birthing room bed and waited.

“An indoor shower is a real luxury to her,” Sister Angela said. “Normally she just sprays off with a hose in their yard. She’s one of our poorest clients. She’s also a very special woman.”

Growing impatient, Sister Angela knocked on the bathroom door. A wet-haired Lupe came to the door, and when she saw Sister Angela, she threw her arms around her neck.

The two women talked excitedly in Spanish. Angela touched Kamala on the arm and told Lupe she was a professional. Lupe was in good hands, she said.

When the evening became early morning, Lupe pleaded with Kamala to break her water: “Rompe la agua.”

Kamala struggled with whether she should induce the birth. Lupe was weary. The baby’s head was positioned high in the uterus and breaking the water too soon could hurt the baby by cutting off the baby’s supply of oxygen before it was born.

By 2 a.m., we had bathed Lupe in a warm bath, we had tried to get her to lie down and rest. Lupe lay across the double bed in the birthing room, her legs bent, the bottoms of her feet grabbing at the edge of the bed. Kamala strapped on a pair of sterile gloves and then reached her arm up between Lupe’s legs trying to feel the baby’s head in her uterus.

“It’s still really high up there,” she said to me and then translated for Lupe.

Kamala took out the ultrasound box and its long steel probe. She squirted lubricant on the probe’s flat end and began moving the instrument around Lupe’s bulging stomach. The box squelched like a bad radio transmission as she moved the probe. Normally, the high-pitched screech turned into a soft beating that became louder and louder until it emitted an eerie rhythmic thumping. This time, though, all we heard was the squawking of the machine.

The probe in Kamala’s hand slid across Lupe’s skin, leaving a trail of grease in its wake. Kamala nervously adjusted the knobs on the machine. Then pushed the probe to the outer portion of Lupe’s stomach. The squelching of the machine began to soften, and we heard a quiet thumping that grew louder and more clear. Kamala sighed.

“I was really worried for a while there,” she admitted.

Kamala picked up several fat, orange envelopes that contained Lupe’s medical records and read details that disturbed her. On her last two births at the clinic, Lupe had lost an unusual amount of blood. She also had uterine atony — when the uterus doesn’t contract.

“I wish she would stop pushing,” Kamala said. “She’s determined to have this baby right now, and she’s tiring herself out. She’s going to need that strength later.”

At 3 a.m., Kamala’s shift ended. She phoned the next midwife on duty, Abigail Reese, a 28-year-old with long dark curly hair, cat green eyes and perfectly arched eyebrows. In September, having just graduated from Yale with a masters in midwifery, Abby signed on as a paid staff member for two years at a salary of $1,000 a month. She was the first staff midwife who was not a sister.

Although Abby had placed the hall phone next on her pillow, she didn’t hear the 10 shrilling rings and had to be awakened by Sister Lori Sills, whose room is next door.

Abby reluctantly pulled on her pink scrubs and rubbed the sleep from her eyes. Outside, she walked under the sway of the willow trees, the night breeze blowing her hair. She heated some coffee, and then headed over to the farthest birthing room at the center.

Lupe had returned to her feet and was pacing around the birthing rooms again stopping only to pester Kamala to check whether the baby had fallen into the birth canal. Kamala put her off.

“I’ll let someone who is coming into this fresh make that decision,” Kamala said, sleepily.

Kamala explained Lupe’s situation to Abby. Then she hugged Abby and wished her luck.

Abby helped me rub Lupe’s belly during contractions. When the pain started, Lupe could hardly stand. She wrapped her arms around our shoulders, and we held her up. Abby checked Lupe frequently, but still the baby’s head was too far up. Lupe’s contractions continued to increase in frequency and duration. She pushed harder, her face strained, her red cheeks mashed up to closed eyes. Her teeth ground together as she sucked in air and sprayed out spit.

I had expected Lupe’s labor to last a couple of hours — as it had when I helped my sister-in-law give birth in the hospital. But as the hours added up, I began growing more frustrated and helpless to relieve Lupe’s escalating pains. I was also angry that the father of Lupe’s baby wasn’t here to help her, that she was left alone at such a critical time.

As I watched Lupe suffer through the contractions, my admiration grew. I questioned whether I could ever endure the agony that Lupe seemed to accept. Was it through this pain that mothers bond quickly with their children, I wondered. I felt torn by the experience — while there was so much beauty in the warmth and love of the women who surrounded Lupe, who tried to ease her pain, who would share in her joy and her relief when the baby finally came — there seem to be such needless suffering, too. I wanted so much that Lupe could have an epidural, that she could enjoy this moment without immense exhaustion.

About 4:30 a.m., Lupe sat on the edge of the bed and cried, her face in her hands. Abby kneeled on the floor with her hands on Lupe’s legs. These were the crazy hours before birth when women get angry and irrational. Abby took Lupe’s increasing moodiness as a good sign. Then things got ugly.

Lupe screamed that if Abby wasn’t going to break her water, she wanted to go to the hospital. She cried exhausted tears that begged for sleep, for food, for an end to the pain. When Abby tried to explain the dangers, Lupe demanded to see Sister Angela. Abby looked up at Lupe. They were only two years apart in age but thousands of dollars apart in education and life experience.

“I’m a product of circumstances like anyone else,” Abby would tell me later. “I can’t minimize that privilege got me where I am, and the lack of privilege got her where she is.”

Abby tried to assuage Lupe with her eyes. She rubbed Lupe’s legs and spoke to her softly. In the end, it was Abby’s calm presence that settled Lupe.

About 6 a.m., Abby checked Lupe again and found that the baby’s head had moved farther down. It was time to break the water bag which had ballooned up against the side of Lupe’s uterus. Abby called Sister Mary who was on duty as back-up.

The Texas sky was fading from black to dark blue when Mary walked over from her room just a few buildings away. She was sleepy, but after years of rising early at the convent and decades as a labor and delivery nurse and then as a midwife, Mary was accustomed to rising before dawn. Sister Mary Thompson is a red-headed woman with freckles and fair skin and speaks in a Wisconsin accent. She is Angela’s second in command.

Sister Mary reviewed how to insert the amniohook that would prick the water bag.

At 7:03 a.m. Abby squatted down on the floor beneath Lupe’s legs and did just as Mary told her. There was a rush of fluids and within minutes the baby’s head began to crown. Sister Mary lay on the bed next to Lupe. She held Lupe’s hand and showed her how to breath as she herself pursed her lips and took short, dramatic breaths.

Abby crouched below Lupe’s legs with her gloved hands holding the baby’s head.

“Okay, stop pushing!” Mary said, in English and in Spanish.

And then the brown little head appeared. Then a shoulder. A belly. The long yellow umbilical cord between the legs.

Abby held the wet baby in her arms. The nurse noted the time: 7:15 a.m.

“It’s a girl!” Abby said.

“It’s a girl!” we all said in chorus.

Lupe smiled and lifted up her head to see her baby. Abby wrapped the baby in a blanket and the nurse suctioned out the baby’s nose. Then, she placed the baby with the umbilical chord still attached on top of Lupe’s stomach. Lupe had delivered a healthy baby girl, 8 pounds, 13 ounces. She named her Maribel.

I was sitting on the bed next to Lupe, practicing my Spanish. Maribel was lying in the crevice between Lupe’s arm and her stomach. The baby wore a turquoise beanie and was wrapped tightly in a wool blanket to keep warm. It had been more than two hours since Lupe had given birth. She had eaten breakfast and breast-fed the baby. Now she lay on the bed, her eyes half-way open.

“Do you have pain? Are you bleeding?” I asked in Spanish, reading from an English-Spanish baby delivery book.

Lupe smiled. She liked it when I tried to speak Spanish to her. She answered in long sentences, strange words that flung from her tongue. Then she put her hand on her vagina and tensed her eyebrows.

“Sangre, mucho sangre.”

I understood that much.

“She says she’s bleeding a lot,” I told the volunteer nurse, 27-year-old Nicole Lassiter, the only one in the room with us. Everyone else had gone for breakfast or to take showers or to check on patients who were crowding the waiting room.

Nicole pulled back the covers to reveal a large puddle of blood beneath Lupe. She rushed to the phone and pushed the intercom. “Mary, Abby, stat!” she said.

Nicole returned and checked Lupe’s pulse and felt her stomach which seemed bloated. When Sister Mary and Abby ran into the room, Nicole pointed to the blood. Sister Mary told Nicole to push hard on Lupe’s stomach. “Even to the point of hurting her,” Mary said.

Nicole pushed hard. Blood gushed between Lupe’s legs. Lupe fainted.

“Oh shit!” someone yelled.

Sister Mary started an IV into Lupe’s arm, while Nicole kept checking Lupe’s pulse and blood pressure.

“It’s now 50 over 20!” Nicole said.

Just then Sister Anita Jennissen, a tall, tanned silver-haired woman with deep-set dark eyes, sauntered into the room brimming a large smile. “I heard Lupe had her baby and I came to see how she’s doing,” Anita said cheerfully.

“Anita, this is not a good time!” Mary said. “If you want to help, start praying for her.”

Anita hurried to the head of the bed. Brushing back the hair on Lupe’s forehead, Sister Anita tried to console Lupe, telling her in Spanish that she should try to relax. But Lupe wasn’t responding.

“Let’s give her some oxygen!” Sister Anita said.

Mary wheeled over the oxygen tank and handed the mask to Sister Anita. Then Mary took the baby and handed her to me.

With her hand on Lupe’s head and her eyes closed, Sister Anita prayed quickly in Spanish. The room filled with the eerie sounds of foreign words accentuated with medical terminology.

“Vamos a pedir a dios por la intercession de la Virgina de Guadelupe,” Sister Anita prayed to Our Lady of Guadelupe — Lupe’s patron saint.

Lupe came to and began moaning.

“Maybe we should get an IV going in her other arm,” Mary suggested.

Nicole kept pushing on Lupe’s stomach to push out the blood clots. Lupe cried, muttering in pain. Anita held her hand and prayed: “Dios de salve Maria.” — God save you.

The day after Lupe’s delivery, Delia Rodriguez, a Mexican clinic staffer, drove home Lupe, Maribel and Lupe’s mother. After Lupe’s dangerous hemorrhaging, the sisters had insisted on bringing in Lupe’s mother, a stooped, bucktoothed woman who wore a constant smile and nodded her head when she talked. Though the temperature was in the 80s, the old woman wore a heavy jean skirt, a long sleeved shirt and a thick sweatshirt advertising a 10K race in Houston, a city the woman had never visited.

The sisters had kept Lupe an extra day because of her blood loss, but that morning Lupe sat smiling and laughing in the front seat of the Suburban. The car was packed with boxes of food and clothes and diapers. Delia wielded the Suburban skillfully around the pot holes of the back roads headed toward Progresso. Delia and Lupe sang along with the Spanish love songs on the radio.

Delia had been a migrant worker at one time but now she worked as a nurse’s assistant at the clinic. She was a large woman with a ring on every finger and always wore her hair in a tight bun like a crown on the very top of her head.

Eventually the black top road we were on ended and we drove through a muddy lane in a cow field. A half a mile walk through the field stood the United State’s barbed wire fences and the ominous border patrol. Delia was afraid to keep going with the ruts more than a foot deep. But Lupe assured her she wouldn’t get stuck because other cars passed by there all the time, she said.

Delia pulled up to the family’s compound of scrap metal shacks. A fence around the property was crafted from fragments of barbed wire, wood and aluminum. At the gate, a lanky gray-haired man neatly dressed in a light blue office shirt and gray trousers stood next to a young woman with long dark hair. He was Lupe’s father and she was her younger sister. We carried the boxes and the baby basket but her family took them at the gate. Inside the fence, several mangy mutts lay around a dirt yard scattered with odd machine parts – an old washing machine and something that looked like a lawn mower.

Angela had warned that Lupe probably wouldn’t allow us inside her house because she was too embarrassed. “She always meets you in the yard,” Sister Angela had said.

As Delia buckled herself in, we watched Lupe’s mother pull wild herbs from beside the road. “They are our poorest clients,” Delia said, “but Lupe never missed a single check-up. She was always there.”

Delia backed the Suburban into the muddy lane, but when she put the car in drive, we heard the vicious circling of the tires and the engine racing to try to dig us out from the slop. Lupe’s father, stood in the road, and after several attempts, helped push us from the muck, leaving speckles of mud all over his shirt and pants.

Three days after Lupe left Holy Family, she was scheduled for a home visit by her nurse-midwife, Abby.

That afternoon, I drove down the narrow back roads that led to Progresso. Abby was tending to a patient and promised to arrive shortly. The sun was beginning its descent in the sky casting intense orange light on the wild grasses and the cattle that grazed next to Lupe’s house. I pulled the car into the weeds where the blacktop ended and walked past the neatly painted, soap-box houses next to the Aranda compound.

Lupe’s sister, Rose, met me at the gate and led me through the yard where chickens and roosters marched like proud landowners in the dried dirt. Her brothers and Lupe’s children were out in the field burying a dog that died that morning, she said. Lupe’s aunt had kept the dog tied up outside her boarded-up portion of Lupe’s house. The dog was rarely fed, and it died of starvation.

Rose is 20 years old and has a wide, open face and a direct gaze that is uncommon among illegal women. She carries herself like an American tomboy — gutsy, self-assured. Last year, Rose graduated from high school and speaks excellent English — with hardly a hint of an accent. When I asked her if she had any children, she recoiled. “I think there are enough kids around here,” she said. “I am single.”

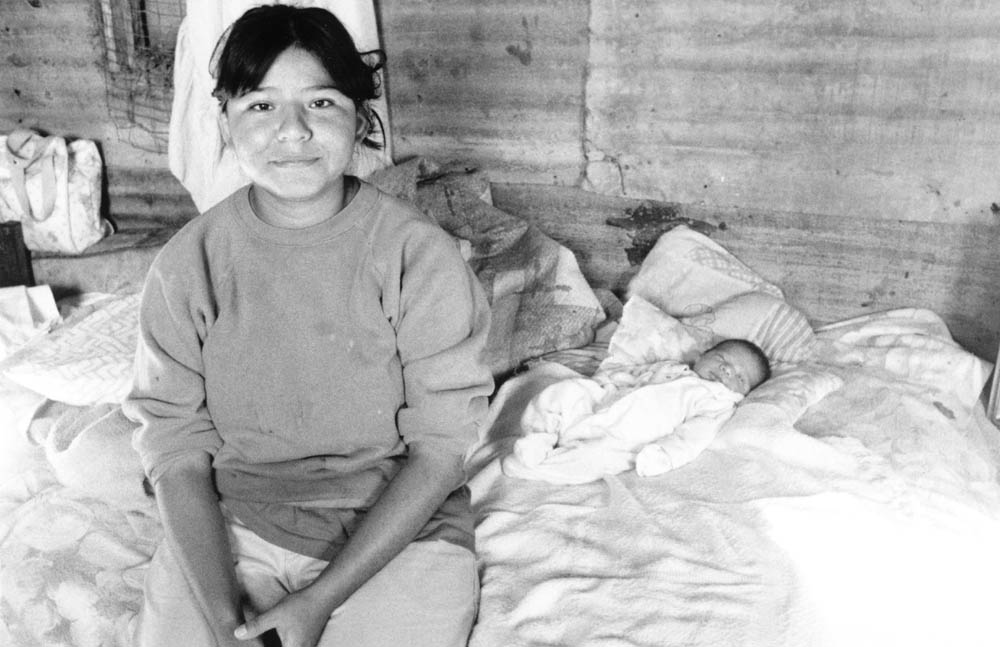

Nicole Lassiter (nurse) and Maria Guadelupe Aranda (Lupe).

She is also bright. Rose’s high school English teacher saw promise in the young woman and helped her fill out papers to try to get into local colleges. But because she is not a U.S. citizen, Rose would have to pay international tuition rates and wouldn’t qualify for U.S. government student loans or scholarships. Higher education was out of her reach.

Although Rose has working papers and would like to get a job, the family doesn’t own a car, and most of the jobs in the classifieds are in the bigger cities that are at least a 20-minute-drive away. There is no bus service. So, Rose stays on the farm and helps Lupe with her four children. When she speaks about her family’s austere poverty and the American dream that is only a wild fantasy for her, there is no bitterness in her voice— just resignation.

Rose showed me around the property and explained the function of each tiny, scrap-metal building. Across from Lupe’s house stands a small one-room house where Rose, her two adult brothers and her parents sleep. “There’s just barely enough room,” she said. “My brothers sleep on the floor.”

Lupe and the author.

The Arandas are allowed to stay on the land as long as they tend the horned cattle that live in the pasture next to them. But they still have to pay $200 a month rent for the use of the shacks — in addition to their electric bill. On a light pole at the far end of the property is an outlet with several cords flowing to the various buildings.

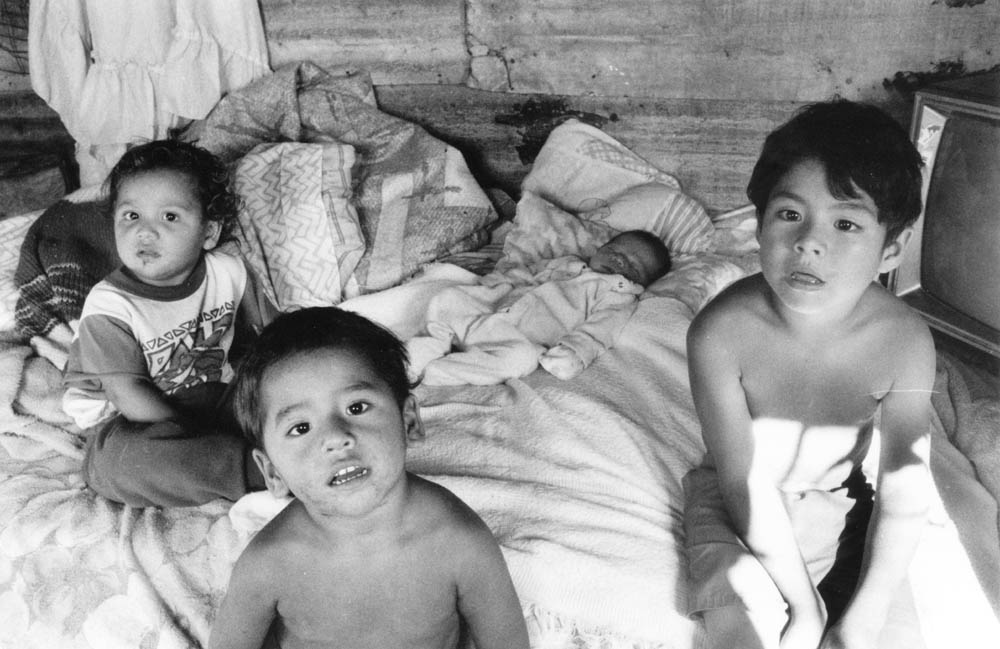

Outside the door of Lupe’s aluminum house, an old washing machine churned clothes as soap suds bubbled down the vibrating legs. I ducked inside the doorway. Lupe’s three children followed. Juan, 5, and Rene, 3, were barefoot and shirtless. Angelica, 2, looked like a boy. She had big brown eyes and short curly hair tangled with straw.

Beneath my feet, the hard dirt formed the floor. Extension chords hung from the ceiling along with thick cobwebs. Lupe’s side of the house was divided by a partition with a stove and boxes in the front room and two small cots in the back room. Lupe sat on one cot and was breast-feeding Maribel. She grinned when she saw me and offered me a seat on her bed.

A few fleas jumped from the polyester blanket that neatly covered her bed, and mosquitoes buzzed around the dark room occasionally lighting on the arms and legs of their next victims. Lupe shooed them away from me, concerned that the mosquito tracks on my arms had come from her home.

At the head of Lupe’s bed was an old television set.

“Does it work?” I asked.

She nodded her head and proudly turned on the machine which piped in Oprah with an amazingly sharp reception. She turned the dial to show reception on three different stations. For a few minutes, we sat in the dark house starring at the television with the blue light shining in our faces.

Then, Lupe turned off the set and opened a wooden window flooding the room with the rays of the western sunset. In the field, her parents were cooking dinner over an open fire. A few feet from the window cows lay in the grass.

Lupe finished breast-feeding and handed me the baby while she went to the outhouse. Maribel wore a knitted sleeping outfit and was sweating. Her brothers and sister lovingly patted her head as they smiled big, baby tooth grins beneath mustaches of mud. Occasionally, one of the chickens would run into the house and the kids, laughing, would chase it out.

Rose stood in the doorway of the house and asked me if I was hungry. They were going to go chop down sugar canes in the field, she said. From the window, I could see her swinging a butcher knife. And not long after, she returned carrying long, thick greenish canes. The kids ran into the house sucking on them like lollipops. Rose handed me hers and instructed me how to rip out the yellow threads with my teeth, suck out the sweet juices and then either swallow or spit out the remaining pulp. The meat of the cane was thick and coarse and the juice reminded me of pineapple.

As the kids sat on the dirt floor chewing on their canes, Lupe had them speak a few words in English for me. The oldest, Juan, attended the local kindergarten where he is learning the language. Lupe took out a stack of pictures from a box and showed me her daughters who live in Guatemala. They were impeccably dressed in matching red and white dresses with their hair braided and tied with ribbons. In another picture, they were dressed like Hawaiian hula girls wearing grass skirts and flowered necklaces. The house where the girls lived with their godmother resembled nothing of what I saw around me.

I asked Lupe if she had any pictures of the four children sitting around her. She shook her head. I took out my camera and the kids stared at the black object in my hand. Lupe combed their hair with her fingers and wiped dirt off their faces with a licked thumb. Then she lined them up in front of her as she held the baby. But the kids didn’t know to look at the camera, and their eyes roamed. They fidgeted. After several frames, Rose asked for her picture to be taken. She stared wide-eyed into the camera and smiled.

Lupe’s sister Rose & Maribel.

A few minutes later, Abby arrived. She had gotten lost, she said, having driven across the bridge to Mexico several times because she couldn’t find Lupe’s street. Lupe lives on one of the last turnoffs before the Mexican border.

Abby examined Lupe and the baby while Lupe and Rose told jokes. Baby and mother appeared to be in good health, Abby said. Afterwards, Lupe questioned Abby about her credentials, how long she went to school and what degrees she had earned. Then she pulled Juan to her side and pointed at Abby. “See this lady,” Lupe said in Spanish. “She went to school for a lot of years and if you go to school you can be a policeman or a fireman or a doctor.”

Abby sat next to Lupe on her bed and looked around the shack. Lupe told her the house was eight years old and when it rains, the water pours through the slats where sunlight now filtered. One night one of the boards fell down and hit Juan in the head and gave him a black eye.

“Lupe, it seems like you need a new house,” Abby said, thinking out loud.

“Oh no. For someone who’s poor, this is nice,” Lupe proudly insisted. “It just needs to be fixed so water won’t come in.”

As I was leaving, Rose and Lupe offered me tamales her parents had just made. The kids were walking around eating theirs in their hands. Lupe showed me around her yard and introduced me to her parents again.

At the gate, Lupe hugged me and said, “Thank you,” in perfect English.

As I drove away from the house, I saw the INS helicopters buzzing in the sky above the fields next to the Aranda’s shacks. They were searching for illegals who had swum the river, climbed through holes in the fences and were hiding in the fields.

Other pictures at Lupe’s Home.

It was just a normal day in the life of the border patrol trying to stop the illegals who live everywhere in South Texas — even in shacks within yards of the border. As I steered through the pot holes beneath the whirring choppers, I remembered what Abby had once told me: “It’s a limbo land. If someone blind-folded you, would know where you were?”

©1999 Cheryl Reed

Cheryl Reed, a freelance writer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is examing aspects of the Roman Catholic Church.