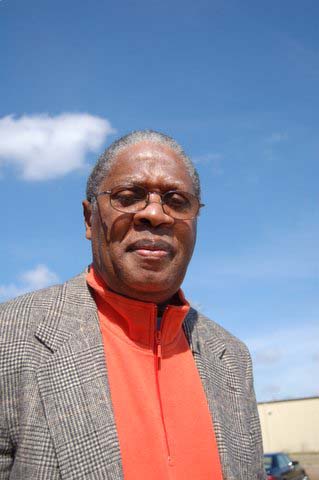

MARION, Alabama – Reese Billingsley, insurance salesman and member of the county’s tiny black middle class, eased his Model-T Ford off the dirt road into the cotton field, and blew the horn.

“You see, she told me not to come up to the house,” the 76 year-old explained over lunch at Lottie’s diner, just off the town square, half a century later.

“She says to me, the first time I was out there, ‘you toot the horn, and I’ll bring the premium down to you.’ So I laid down on that squeaky horn a bunch of times. Well, directly, here comes Dr. Jones down the hill. He drives up to me and says, ‘what’re you doing here?’ I told him, I’m just selling a little insurance. So he goes, ‘let me tell you one damn thing, insurance don’t feed these “n…..”s, we do.’

“That’s a good bit of how it was back then” he says picking at a chicken wing and finishing off his sweet tea. “That was a different time.”

That was the Alabama Black Belt in the early 1950s, a place that owed its existence to the soil, the deep dark earth, the kind that grows cotton, the kind that stretches from central Alabama west to Texas and east into the Carolinas, dirt that gives the region its name.

The land also grew plantations, and to work them, planters in antebellum Alabama needed slaves. So they brought them in by the thousands.

After the war, freedmen stayed, and their children after them. They worked as sharecroppers and tenants, gained the vote and then lost it, and came to consider Jim Crow just one more burden they had to bear until they were called home to Jesus.

Today, there isn’t much left of the farms and folks Billingsley knew back then. That era in Perry County, his county, is as much a place in the mind of the people as it is a place on earth, a memory of when the majority was oppressed, subservient and disenfranchised. It is a representation of tyranny passed, of an exceedingly dark chapter, a long chapter that seemed never to end.

It is Gone Time. It is also today.

From the 1950s, life would get worse for Reese Billingsley and most other blacks who formed a majority of the population in this part of Alabama, worse before they would get better.

He can tell you all about that too. On the night of Feb. 18, 1965, he was across the square from Lottie’s, outside the Zion United Methodist Church, when state troopers and local thugs attacked and beat peaceful demonstrators and a young black man named Jimmy Lee Jackson, who had repeatedly been denied the right to register to vote, was fatally shot by Alabama Trooper James Bonard Fowler.

Of course, Billingsley is not the only person around town who can recount that evening to you. They are everywhere.

The viciousness of the attacks and Jackson’s death a few days later outraged and energized the leadership of the civil rights movement, providing a catalyst for the Selma to Montgomery March and for Bloody Sunday, when troopers again attacked peaceful demonstrators attempting to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Those events infuriated the nation and brought a renewed determination by civil rights leaders and their allies in Washington to push for full voting rights. The opposition, which had vowed never to give in, crumbled and in August of that year President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

And Alabama’s Black Belt began to change.

Come here today and you will see that political empowerment, of perhaps some of the most disenfranchised people in the United States, has been achieved.

No, the Dr. Joneses of Perry County don’t speak to Reese Billingsley or other blacks in that old way, anymore.

In fact, most everyone today addresses Billingsley with the respect deserved of a man who works in the Voter Registration Office of the Perry County Courthouse.

With a few key strokes on a computer he can show you that there are 6,006 black registered voters in the county. “That’s up from a couple dozen maybe in 1965,” he says with a grin.

The Challenge of Empowerment

The political landscape of the entire region has therefore changed. Blacks now hold office from city hall to the U.S. Congress throughout the Black Belt, wielding enormous power at the local level, holding influential positions in the Alabama Legislature, with a potentially well-positioned representative in Washington.

Times have indeed changed.

Yet there is also this:

The U.S. Census Bureau in 2000 put the percent of people living in poverty in the United States at 12.5.

In Alabama it is 16.1 per cent.

In Perry County is it more than 35 percent.

The per capita income of the United States is $21,589. In Alabama it is $18,189. In Perry County is it $10,984.

In the Black Belt counties surrounding Perry, the picture is much the same. The percentage of people living in poverty ranges from a low of 26.9 percent in Hale County to 39.9 percent in Wilcox County, while per capita income spans from $13,686 in Greene County to $10,903 in Wilcox.

For blacks, the statistical picture is even bleaker. While 35 percent of the total population in Perry is considered impoverished, 45 percent of all blacks in that county live in poverty. In Dallas County, it is 43 percent. In Wilcox, the percentage of blacks living in poverty is 50 percent, according to the Alabama Poverty Project.

The region also has been witness to a steep drop in population in the last four decades. Perry County is typical. In 1960, some 17,300 people made it their home. By 2000, the population had fallen to around 11,800.

The infant mortality rate in the United States is 6.8 percent. In Alabama it is 9.1 percent. The average in the twelve most impoverished counties constituting the traditional Black Belt is 10.3 percent, according to the Alabama Center for Health Statistics.

The numbers, then, beg this question: What is the quality of the democracy that has been achieved in Alabama’s Black Belt?

Why is poverty so doggedly high here? Why has the area’s industrial base and population shrunk since 1965? What is holding the place back?

The vote, to begin

“Seek ye first the political kingdom and all else shall be added onto you.” – Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, 1960.

Closer to home, just to the east of Marion, in downtown Selma, you will not get any argument with that sentiment from one of the Black Belt’s rising politicians, a state representative named Yusuf Salaam.

But, then he’ll also give you this: “politics don’t put money in your pocket.”

He and other black leaders will point out that complex problems bedevil the Black Belt, including a changing global economy, the demise of the great plantations, lack of infrastructure, a poor public education system, a weak state government and the allure of a better life elsewhere that drains the area of great minds and leaders. All this, he says, has helped Alabama’s Black Belt counties remain the poorest in the state and some of them the poorest in the nation.

Merle Black is a political science professor at Emory University in Atlanta and the author of several books about the South. For him, the outlook for the Black Belt is bleak for obvious reasons.

“There is nothing going on for them,” he said from his Emory office. “A state like Alabama has limited resources, so they are going to put it where it is going to have a return, not in the Black Belt. It’s the same with industry. Additionally, of course, you have an issue with leadership. Most of your quality leadership doesn’t want to be there. The good leadership leaves the place.”

But some of those same leaders also lay the blame for the ongoing problems squarely at the feet of the region’s politicians. Leadership, or the lack thereof, has been an impediment to progress, many here and elsewhere say. The politics of race, never far below the surface in Alabama, bubble up here in a way that keeps the place down.

“You either own power or you don’t,” says the chairman of the Perry County Commission, Johnny Flowers, 56, as he drives a visitor along a rutted country road, drinking coffee with one hand, fiddling with a cell phone with the other, holding the wheel with his knee.

“We don’t want to share the power. We have leaders who won’t dare work with white leaders. That’s our problem. We aren’t using all our resources.”

Albert Turner, Jr., is also a Perry County Commissioner and the head of the Perry County Civil League, an influential organization started by his father, the late Albert Turner, Sr. – a courageous local leader during the civil rights movement. He doesn’t put it the same way as his colleague.

“Perry County is not the real world,” says the 40-year-old Turner from his office in Marion. “Everything is divided by race. People call for racial harmony, but there is none. There has to be an overt effort from the Caucasians to say let’s link up and hold hands. It’s like this: They want to keep you poor. They want to keep you from getting money in your local schools. And they are the ones who are the sons and grandsons of those who stole the land, when cotton was king and white man’s law was the law of the land.”

Changing Times and Politics

In addition to continuing economic problems, high poverty rates and dwindling population in the four decades since black political empowerment has come to the Black Belt, the region has been beset by what some would describe as political instability. Going back to the early 1980s, state and federal officials had probed instances of voter fraud, elections have been overturned because of absentee voter fraud and a number of local politicians have been indicted for vote rigging.

“After every single election we have these accusations of fraud,” said Jimmy Thomas, an assistant district attorney in Selma. “It never fails, after every election we have these complaints.”

Blacks and whites also consistently complain of voter intimidation and dictatorial tactics by local political bosses.

All of this has a very familiar ring to District Judge Sonny Ryan of Greensboro, Ala., in Hale County just to west of Perry.

“Clearly, there was some bad leadership and voter fraud here before blacks gained political power,” Ryan said in his courthouse office in Greensboro. “When the majority finally took control in the Black Belt, a lot of the black politicians said to hell with you. But who do we have to blame for that? Us, the white political establishment, that’s who. Some white leaders had a very big part in creating bad political leadership in this part of the South.”

Others readily acknowledge that the segregationalist era and centuries of oppression are clearly part of the problem. Johnny Flowers, who has been in office for 18 years, will tell you for example that it took him years to gain the confidence and to learn the workings of government enough to even begin to be an effective leader.

But those who have been part of society here and long studied this part of the South also stress that opportunities have been lost, in a big way.

“A lot of people and industries don’t even want to come to the Black Belt and Perry County because of many of our politicians,” says Ed Daniel, a former black mayor of Marion.

“Too many of them aren’t looking at the big picture,” he said on a recent cool afternoon in Marion.

“When it all comes down to it, we all need clean drinking water. We all want to come together to solve our common problems. If the egos would get out of the way, we might be OK.”

Wayne Flynt, one of Alabama’s best known historians, a former professor at Auburn University and author and co-author of a number of books on the state, including “Poor But Proud,” agrees.

“What you see in much of the Black Belt is that the gains of one generation have been lost by the selfishness of the next,” he said.

“Protecting turf, and gaining power and entrenching oneself in power. This is the way represented by leaders like Albert Turner, a way formed by the condition of apartheid, of white supremacy. His father was angry and he is angry.”

He points to a number of other powerful black political figures, past and present, in the Black Belt who he says have spent far too much time protecting their base than working toward moving the area forward.

Flynt’s overall reading of the political landscape of the region, however, is mostly about hope.

He argues, for example, that one of these politicians, state Sen. Hank Sanders of Selma, especially – a smart, charming and rotund man – has more recently drifted towards more pragmatic political stands.

Today, Sanders is perhaps one of Alabama’s most powerful politicians, overseeing billions in state revenue.

From his law office near the banks of the Alabama River in Selma, he listens politely to this analysis of his supposed political drift before a smile cascades across his face.

“I may have matured during my years in office,” said the Harvard-educated, 23-year veteran of the Alabama Legislature. “But I haven’t really changed. It is more of a case of the landscape changing and people drifting more towards me.”

Certainly one or the other has happened, because whites are not only now voting for Sanders, they are throwing fund-raisers for him.

That’s an addition to Wayne Flynt’s message of hope from the Black Belt. He’s gotten to the point where he has little patience for those policy and economic advisors to the state government and political scientists who have consistently dismissed the area with a refrain that goes something like: the best thing to do with the Black Belt is to build a four-lane highway through it so everyone can get out quicker.

“You see, people just can’t live, they can’t go on, believing that,” he says with more than a little emotion from his home library across the state in Auburn. “You can’t just write it off and kill the dream, because that strikes at the very heart of Alabama’s Christian message, that resurrection is always possible.”

The Black Belt Shall Rise Again?

A hint that resurrection is on the way, he says, comes in the form of a Black Belt politician who is about the politics of problem-solving rather than the politics of race and division.

Congressman Artur Davis is a 38-year-old former assistant U.S. attorney from Montgomery and Harvard law graduate who managed to beat the powerful incumbent, Earl Hilliard, Alabama’s first black member of Congress since reconstruction, in 2002.

In his 2004 reelection bid, he took 75 percent of the vote in the general election.

Listen to him talk to a standing-room-only crowd of black businessmen and white farmers at the old railroad depot in Marion and you hear a man who speaks of the need for subsidies for catfish farmers on one hand, while explaining the criminality of the Republican-controlled Congress attacking the food stamp program on the other.

Everyone claps, and everyone who speaks takes a moment at the end to thank the congressman. “We are very proud of you” a white catfish farmer tells him.

In towns, on county commissions and on the ballot are an increasing number of blacks who are gravitating away from platforms built around race and the events of the civil rights movement and toward Davis’ politics of problem-solving, Flynt and others say.

Examples abound.

Thirty-eight-year-old Phillip White, mayor of Uniontown, Ala., in southern Perry County, is a soft-spoken black graduate of the University of Alabama.

“I do not take for granted what was done before,” he says from his funeral home in Uniontown. “We wouldn’t be here otherwise. But listen, you have to be inclusive. You can’t cling to the 1960s. I don’t care who gets credit as long as we can get some economic development going around here.”

Fairest Cureton, a school teacher, and preacher at Zion Methodist, and the first cousin to Jimmy Lee Jackson, is challenging Johnny Flowers for his commission seat in the upcoming Democratic primary.

“If Dr. Martin Luther King was to come and see what life is like for many people, in the Black Belt,” Cureton said from this pastor’s office at Zion Methodist, “he would say that his dream has not come to be fulfilled.

“The same people who want to lead us are now doing what whites used to do to us. We live paycheck to paycheck. This is the legacy of our black leadership here,” said the 49-year-old Cureton.

He skates close to indignant with what he describes as the hijacking of his cousin Jimmy Lee Jackson’s name by the Perry County Civic League. Long ago, he says he stopped attending an annual memorial service for Jackson; a service he and others here claim is a fund-raiser and political rally for Albert Turner and the Civil League. Jackson’s grave headstone notes the contribution of the Civic League.

Next door in Dallas County the politics are complicated, especially in that bastion of intolerance during the civil rights movement, Selma.

Selma has its first ever black mayor, elected in 2000 and a majority black city council, a far cry from March 1965.

But many will tell you, from whites in the business community to black community activists, that race is still very much a part of everything in Selma.

As is often the case in the Black Belt, people will turn to The Old Testament to illustrate a point, especially a political one.

Such is the case with Dr. Park Chittom, a white long-time Selma resident, champion of racial healing and deacon at Selma’s First Baptist.

“If you read the Book of Nehemiah, you will understand our problem,” he said from his Selma office where he has practiced for 30 years.

Prompted, the doctor gives the summary of the Old Testament figure who set out to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem, but was hounded by two characters, Sanballat and Tobiah, because they saw this progress as eroding their influence over the Jews.

“We’ve got a lot of Sanballats and Tobiahs around here,” he said. “It isn’t in their interest for us to move forward. It is in their interest to keep people poor and ignorant.”

Rebuilding is clearly on Kobi Little’s agenda.

The 34-year-old is a candidate for Dallas County probate judge.

Little, an associate pastor at Tabernacle Baptist in Selma, uses the political science language he learned at Johns Hopkins University while lacing it with scripture from Exodus and the Gospel of Luke to make the point that he is inclusive, pragmatic and above all, interested in pulling the region out of depression.

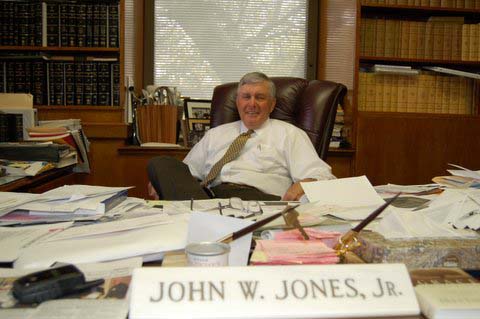

If Little wins, he will replace Judge Johnny Jones, a white man who has held the office for 27 years and will occupy an office just down the hallway from the entrance where Martin Luther King Jr. was repeatedly turned away with hundreds of blacks attempting to register to vote, just inside the door where Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies arrested and violently turned back would-be voters.

“We’ve been 40 years in the wilderness,” he said from a hotel lobby a rock’s throw from one of the most recognized images of the civil rights movement, the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

“We were delivered from injustice. But God wanted his people to live in the land of milk and honey. Yes, we should celebrate the crossing of the bridge. But we also have to understand, that we are clearly on the banks of the River Jordan and that we have got another bridge to cross,” he said.

Ask Jones, the old political pro and he’ll fade from commenting on the personal, such as his impression of Kobi Little. To the general nature of local politics, however, he speaks to a visitor in a frank manner of a man soon to exit political office.

“Until a black politician in the Black Belt can really cross that line and be a reconciler, then we won’t move forward,” he said from his courthouse office.

“There are plenty of blacks out there who could do that, who could bring us together, but they won’t step forward,” he said. “There is simply too much opposition from the black community to change.”

Back in Marion, on a walk around town, Reese Billingsley moves from the business of insurance 50 years ago to the business of politics today.

“A lot of our leaders today, they say, it’s like this: do it my way or not at all. No one person knows everything. The people have to be involved. Some of the black politicians in the Black Belt, they want you to turn to their side, no matter what, even if it’s stupid. They want something from me? Well, I’ll tell you what, I’m not listening to anyone telling me how to grow corn when their crib is empty.”

John Fleming, an editor of The Anniston Star, is reporting on economic and social justice in Alabama’s Black Belt during his Alicia Patterson fellowship.

©2006John Fleming