Text and photos by Jack Coffman and George Anthan

In 1890, the federal Census Bureau announced that the nation’s frontier was closed. It’s opening up again.

The great wave of population, which swept homesteaders onto the Northern Great Plains with the promise of free land and hope for a bright future around the turn of the last century, is sweeping back out again at the beginning of this one. A culture that has been central to the history of America’s westward expansion and whose virtues of simple living, honesty, hard work, and religious faith became the core of how the United States came to see itself, is close to disappearing.

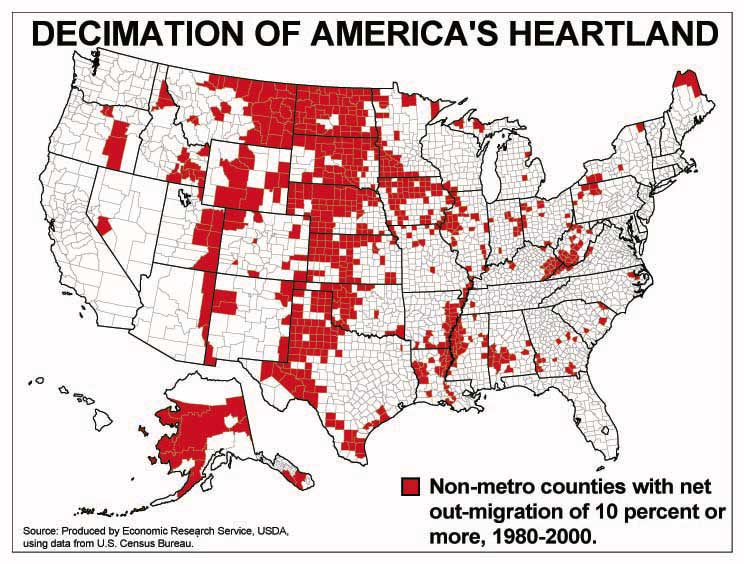

This accelerating ebb of population, which covers a vast swath of America from Central Montana to western Minnesota and southward through North Dakota, South Dakota, western Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas, is leaving behind empty churches, abandoned farms, closed schoolhouses, empty storefronts, and struggling communities like so many conch shells on a beach. Those still living on the rural Northern Great Plains face a daily erosion of the institutions that once provided jobs, education, conveniences, health care, and church life.

It’s ironic that as the nation celebrates the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition, much of the region they opened to European-American settlement is being abandoned.

President Thomas Jefferson, who dispatched Lewis and Clark, dreamed of a land of prosperous villages supported by small farmers. Now, huge grain and livestock operations surround many desolate little towns.

Agriculture, the very reason immigrants were drawn to the Plains in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, now has become an engine for their decline. Federal farm programs, economic forces, and technological advances have promoted bigger and bigger farms and ranches, requiring fewer and fewer people to run them.

Fred Kirschenmann, an Iowa farmer who heads Iowa State University’s Aldo Leopold Center at Ames is blunt about how federal policies have pushed people out of the Great Plains.

“What’s happening is not inevitable,” said Kirschenmann. “We want them to produce raw materials for export as cheap as possible, with as little labor as possible. It’s classic colonialism. The whole region can be seen as a Third World country.”

Mike Korth, who operates a medium-sized farm at Randolph, Nebraska, also blames federal programs that send more than three-fourths of the $10-billion or more in annual subsidies to one-fifth of the nation’s producers.

Korth, who has been active in trying to restructure federal programs, agreed the bias toward bigness “is not happening by chance. It’s happening by plan and design.”

After cresting in the 1930s and 1950s, the rural population on the Northern Great Plains has steadily decreased. Younger people moved to cities. Older people tended to stay. That process has now reached a point where, unless something is done to alter the trend, when this generation of senior citizens is gone, the culture of the Northern Great Plains will virtually disappear, leaving a few islands of urban prosperity along its eastern edge.

Senior citizens have already become the region’s dominant age group. The Great Plains account for 56 percent of U.S. counties with elderly people (65 and older) exceeding 20 percent of the population. The national average is 12.4 percent. The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis recently noted the “graying” of its area, observing, for example, that the over-65 population of Hutchinson County, South Dakota amounts to 26 percent.

The crisis on the Plains became clearer after the 2000 census. North Dakota, hardest hit of the plains states, found that two-thirds of its counties had fewer that six people per square mile, the accepted benchmark for defining “frontier.”

North Dakota became the home of the nation’s fastest shrinking county. The lowest income communities in the United States, once associated with the Deep South, are now in the sand hill country of central Nebraska. Of the counties in the United States consistently losing population, 56 percent are on the Plains.

But it is the draining away of much of the region’s youth and people of childbearing age that many find most alarming.

“What young people wanted was a lifestyle they can’t get out in the boonies,” said former North Dakota Governor Edward Schafer, a Republican who served eight years in the 1990s. “But I am convinced people want to live here. If we give them the opportunities, they will come back.”

Recruiting teachers to rural Plains communities is “very, very difficult…the biggest problem in attracting young teachers is a lack of a social life.”Jay Diede, principal of Watford City (North Dakota) High School, said, “We do a great job of educating our kids. We do a lousy job of keeping them.” Diede said recruiting teachers to rural Plains communities is “very, very difficult…the biggest problem in attracting young teachers is a lack of a social life.”

John Sandvik, 17, a junior at New England High School in far western North Dakota, said, “I don’t plan to stay around here. If you do, there’s a pretty good chance you’re going to lose money.” He lives on a farm.

Parents, said Roger Myers, a Medora, North Dakota rancher, “hope their kids will leave.”

Thus, the great-grandchildren of the immigrants lured by railroads to the Plains with promises of a temperate and fertile paradise are about to complete an exodus that represents an almost total reversal of a movement that had been cited as among America’s greatest achievements.

Three decades ago, in a newspaper interview in Minneapolis, Alistair Cooke discussed his television series, “America.” Asked what most impressed him about the sweep of American history, Cooke said it was the settlement of the Great Plains. Cooke was awed by how settlers were able to endure such a hostile environment and survive.

Now many descendants of those people are losing the struggle for survival, a struggle going on without much notice as the nation concentrates on the Middle East, a sluggish national economy, urban crowding, traffic congestion, and the other problems that concern city folks who make up the vast majority of the nation’s population.

With the exception of excellent writings in the Fargo Forum and the New York Times, the creation of an American Outback in the heartland has drawn only occasional attention from the news media and little or none from Congress.

“We are the forgotten part of the world,” says Diede, the principal whose school was built for 550 students and now has barely 300, and falling.

The Plains continue to provide much of our food, especially wheat and beef, but America is importing more and more along with almost everything else, largely forgetting the lessons of history about the importance of food security.

“As long as it’s cheap and on the shelf, consumers don’t care where it comes from,” said Ron Meidinger, a commissioner in McIntosh County, North Dakota.

“The amount of hopelessness and despair in the Great Plains is pretty severe…. The amount of grief work is immense…. Some fear there will be no one here in 50 years,” observes Rev. Roger Dieterle, a Lutheran minister who serves churches in Medora, Belfield and Daglum, North Dakota, as well as being a counselor.

Even the clergy are becoming depressed, says Sandy LaBlanc, director of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America Rural Ministry in Des Moines. “When you have more funerals than baptisms, you have problems.”

Rural Plains churches are under stress. Many have closed, leaving lovely buildings to wither or be torn down. Ministers like Rev. Dieterle, with his three congregations, are common. Some serve as many as six. Fr. Frank Schuster serves three Catholic parishes in western North Dakota, where he sees the disappearance of a culture as unstoppable.

“I think what’s happening is out of our control,” said Fr. Schuster.

When new ministers arrive at Plains churches, they often do not have sufficient training to cope. LaBlanc said that seminaries serving ELCA churches, the dominant denomination on much of the Northern Great Plains, rarely provide training to prepare clergy, mostly from cities and suburbs, in what to expect.

La Blanc recalled one pastor who was sent to North Dakota with no training and called it “the cruelest thing. The isolation almost killed him and he left the ministry.” Many others, she said, simply move.

“In rural areas, you grow too close to the people – when someone passes away it gets harder and harder,” said Bob Zook, president of the Bethlehem Lutheran Church congregation in Bowbells, North Dakota. Ministers take the losses personally and it wears them down. Zook’s church lost its minister in 2003 and fears it won’t be getting another anytime soon.

Churches are cultural anchors on the Plains. They were among the first structures erected when each area was settled and the last ones abandoned when a community died. Congregations are working hard to stay afloat, sharing clergy, using lay ministers and retired clergy when full-time ministers are not available. Scores of interviews have shown a strong will among those on the plains to preserve not only their churches, but their schools, their health care, governmental services, and way of life.

The large elderly population scattered across such vast areas is putting pressure on the health care delivery system.

“The biggest industry in some towns is the nursing home,” said Jack Zaleski, editor of the editorial page of the Fargo Forum. Indeed, small towns with nursing homes often experience a temporary increase in population as the elderly leave their own communities that lack such facilities.

A study by the University of Nebraska determined that while 20 percent of Americans live in rural areas, only 11 percent of the nation’s physicians are there. The university also found that 70 percent of Nebraska physicians are in just six communities. The Center for Rural Health at the University of North Dakota notes that seven rural North Dakota hospitals have closed since 1987 and that of the state’s 1,380 licensed physicians, only 330 practice in rural areas. Eighty-nine percent of North Dakota counties are considered medically underserved.

“You just can’t find a registered nurse,” says Gretchen Stenehjem, member of the Watford City, North Dakota hospital board. The hospital is hoping to recruit some nurses from the Philippines.

Tanja Wold, a registered nurse, lives with her husband, David, on a ranch 50 miles from the hospital at Watford City in far northwest North Dakota. The stress level, she said, “is very high” among the staff. “The facility is so short-handed that one day I made seven trips to Watford City” to help cope with one emergency after another. “I put more than 700 miles on the car.”

“To see a doctor we have to go to Dickinson and that’s 45 miles,” said Peggy Myers, who works a ranch near Medora, North Dakota with her husband.

“The nearest hospital is 30 miles away in Ord (South Dakota), the nearest doctor is in Burwell 15 miles away and anything major, they send us to Grand Island or Kearney,” said Wade Van Diest of Taylor, Nebraska, a member of the Loup County board.

Lots of agencies are concerned with the disappearing Plains communities. Groups with names like the Center for Small Towns, Center for Rural and Regional Studies, the Aldo Leopold Center, the Center for Rural Affairs as well as several land grant universities and the Federal Reserve Banks of Kansas City and Minneapolis as well as church organizations have all studied various aspects of the issue trying to find a solution.

So far there has been no silver bullet, although there are numerous recommendations ranging from starting organic niche farms to luring big manufacturing to the region with promises of tax breaks. Others see high tech as the answer and still others figure people will move to the plains when big cities just get too crowded or to escape terrorism.

U.S. Senator Byron Dorgan, Democrat of North Dakota, wants to lure people once again to the frontier with a new Homestead Act.

But Zaleski, the Fargo editor, says, “Any effort to repopulate North Dakota is a fool’s errand.”

In many ways, life on the rural Northern Great Plains is a mirror image of everyday life in the nation’s urban centers. Metro areas across American are struggling to deal with rapid growth. Communities on the Plains are coping with rapid shrinking. In metro areas the transportation arteries are clogged with bumper-to-bumper traffic. On the Plains governments are trying to keep roads fixed that carry hardly any traffic. In the city you can buy a house and expect its value to go up five or ten percent the following year. In many Plains communities you can buy a house and expect it to be worth less next year.

Chuck Hassebrook, director of the Center for Rural Affairs at Walthill, Nebraska, a member of the state board of regents asks, “Does it make sense that we have a national policy of emptying the plains, of wiping out a segment of American civilization, while at the same time we have traffic, crowding and sprawl as major concerns elsewhere?”

There have long been boom and bust cycles leaving ghost towns in their wake. But this pales in significance to the vast emptying of the nation’s midsection. However, does anyone really care what happens to the culture on the Northern Great Plains? What would the nation miss if the area became a vast emptiness?

Sam Schumann, chancellor of the University of Minnesota at Morris in far western Minnesota, answered the question this way: “This is the area where the soul of America was forged. It is where the values were formed that distinguish this nation, such as hard work, fairness, honesty, openness to other people and it is an area that has the ability to raise agricultural products the country needs.”

In the midst of this rapidly depopulating region, there are many who love the life on the Plains and don’t want to leave. And there are others who have left but yearn to return.

“These are good people. Hopeful people,” said Jan Zook, lay minister at Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Bowbells. “This is home to us. We are comfortable here. We have a simple life. We aren’t rushed. I feel safe here.”

Tricia Nissen, 30, is a writer for a Twin Cities public relations firm. She grew up on a farm near Valley City, North Dakota, a member of the fourth generation to live on that farm. After graduating from North Dakota State University and marrying, she and her husband moved to the Twin Cities to find jobs.

“Even when I’m not there, I’m thinking about it. We definitely want to go back,” She says.

“In order for me to be a happy person, I have to think I’m going back.”

Rural Migration

Although America was originally a rural place and most of its people lived and worked on farms and in rural areas, things have changed dramatically over the course of the past century. Hundreds of farming and mining towns that were born during the railroad “boom” of the 1800s have long since gone “bust.” And today, after decades of decline, less than 2 percent of the nation’s population live on farms in rural areas. By contrast, more than 50 percent live in metropolitan areas of more than a million people.

Consider, for example, that more than twice as many people live in New York City than on all of the nation’s farms combined.

Why such a shift in the nation’s population? Consider that most Americans once held jobs that relied on the production of natural resources (farming, mining, and related industries), but most of them now work in service or technology oriented industries (customer service or computer programming). And in these industries, employers do not need to be located near the grain elevator or coal mine; they need to have access to large numbers of potential employees with varying skills. As a result, newer industries have concentrated in cities and suburbs, and the large share of jobs that was once in the Heartland has shifted to the cities and suburbs as well.

To put it more simply, technology and other factors have reshaped our national economy. New technologies have allowed American industry, including agriculture, to become so productive that far fewer people and much less money are required to make most products today than were ever thought possible.

With the farm economy and population in serious decline, over the past 50 years, hundreds of thousands of people have left small rural counties in search of opportunities elsewhere. And nearly one third of the nation’s rural counties have seen at least 10 percent of their population depart for other places – literally decimated by the out-migration of people and jobs.

©2004 Jack Coffman and George Anthan

Jack Coffman and George Anthan are longtime journalists for Midwest newspapers who are examining the fate of the Great Plains states during their Patterson year.