A Pullman porter was, before anything, a man who made beds. Or, as they said, made down beds, since the most taxing part was popping the upper berth from the ceiling. The lower was formed by folding down opposing seats, fastening curtains, affixing the headboard, and adding blankets, pillows and linen. An experienced porter could do all that in three to five minutes; some claimed to finish in just 90 seconds, with their hands working independently of their toilworn bodies. Which would be handy since they had to do it dozens more times a night.

The biggest worry was not the bed-making itself, but when to do it, as retired porter Robert E. Turner recalled: “A wise porter will begin making some of his beds just as soon as some of his passengers begin going to the dining car for supper. If he has a heavy load, sometimes he may be lucky, and his passengers may be in good humor and ready to go to bed. Then again he finds one ready for a fight, and if the porter can keep his teeth in sight he may win them over to his side or at least be able to feel that the passenger will forget the whole matter. Several uppers may want to go to bed before the lowers are ready, and they keep looking at the porter, wondering why he doesn’t make their beds down so they can go to bed. They feel that the porter should ask the lowers to vacate their seats so that the porter can make their uppers.”

Most passengers were indifferent to how or when their bed was readied as long as it was, although some who paid attention were impressed. “It was a very strange sight to watch these darkies at their bed-making,” British patrician William Hardman wrote in 1883 of his trip on a Pullman sleeper. “Their rapidity and dexterity were marvelous. Their civility and attention too, were beyond all praise.” Not all British back then held America’s master bed-maker in such esteem. “The porter service is very imperfect and unhealthy,” The Independent newspaper wrote in 1883. “Generally the porter is a man who does not take a bath. His mode of living is irregular. He covers up dirty garments.”

Once beds were made and passengers climbed in, a new preoccupation set in: keeping them there for the night. They might yen for a drink, or need to empty their bladder. The car could seem oppressively warm, no surprise with windows shuttered and the Dixie-born porter wanting to stay toasty while keeping watch, or too chilly, generally a function of the passenger’s age. Sometimes it was just the novelty of having a servant a call bell away, which stoked an urge to ring. A porter’s night was spent shuttling between berths, setting up a ladder so the cherub in Upper Seven could climb down after a bad dream, adjusting the heat for the octogenarian in Lower Two, and answering endless inquiries – “What time is it, porter?” “How long before we pull in to Wichita?” – for the restless sleeper in Upper Eleven.

Nocturnal fidgeting was so much part of life on a sleeper that porters and conductors penned names for passenger types. There was the Chronic Kicker, who never settled in or took his finger off the bell. Captain Smorker, who alternated between picking his teeth with a pocket knife and wiping his oversized brow with a handkerchief retrieved from his hat. Best of all were the Farmer and his Wife. They took an hour to corkscrew their corpulent carcasses into bed and replace street clothes with nightshirt and cap. During the night they would snake their way back from the toilet down corridors echoing with midnight snores, often ending up in a stranger’s berth. Their ultimate fate was to join mothers-in-law, country cousins and the Saturday night bath as peerless prototypes for funny papers and burlesque shows.

Berth attendant was one among many hats the Pullman porter wore. He was official greeter, helping passengers climb aboard and lugging up their baggage, then doing the reverse when they left. He was a chambermaid, endlessly dusting cinders from window ledges and seats, always with a wet cloth to keep embers down, then using mop and whisk-broom to sweep grime off washrooms, passageways and platforms. Spittoons had to be polished, ladies’ hats boxed, letters mailed and telegrams wired, heaters stoked, lights lit and extinguished, Quiet signs posted then removed, card tables set up and broken down, and coolers stocked with ice. In the old days a porter helped the crew load wood for the engine, and sometimes had to traipse into the forest to find it; later he kept the air conditioner humming. He served food and drinks on dining and hotel cars, and sold cigarettes, candy and playing cards everywhere Pullmans ran.

How could a porter keep track of all that needed doing, and do it? Only one way, according to an instruction book from 1888. The conductor must be constantly on the lookout for “any disorder whatever in the car,” at which point he should “call the attention of the Porter to the improper condition of things.” The porter, meanwhile, “should be almost constantly on his feet and working upon the car.”

A Pullman porter also did everything a health inspector or doctor would have, without being sworn in, trained, or protected against illness. He tried to keep off anyone with smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, typhus or the plague; people with other infectious diseases could ride, but only in later years, in a private compartment, and the room had to be fumigated afterwards. He tended the sick and invalid, wetnursed newborns, babysat toddlers, and was midwife to premature moms. All available 24 hours a day, just like in a hospital. Eradicating expectorating was inconceivable, but the porter urged men to aim for one of the spittoons situated at strategic intervals and pleaded with riders of both sexes to forswear flushing until the train left the station.

“They didn’t want toilets flushed onto the platform,” recalls Kenneth Judy, who went to work as a porter shortly before World War II. “Toilets just flushed on the railroad tracks, you know. People would smoke cigars and put them in the cuspidors and we’d empty those into the toilet. We’d flush when the train was running and when it hit the roadbed it would just fly all over everywhere. Same with everything you put in the toilet. Like I say, that was really a steadfast rule: when you were coming into a station you had to keep your vestibule closed so no one would use the toilet.”

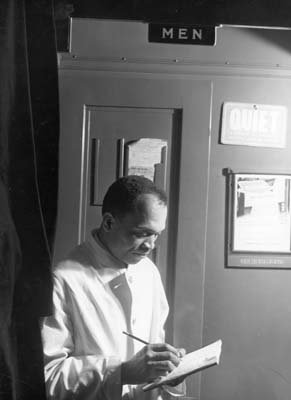

The porter’s true home on the train was the smoking room, and that is where he best earned his title as World’s Most Perfect Servant. Shoes were shined there every night – only black and tan ones, not white, and only one pair at a time the rulebook said, to avoid mix-ups. Pants and jackets were pressed. And since the smoking room doubled as a men’s bathroom, toilets, wash bowls and dental lavatory needed to be scrubbed, mirrors polished, soap dispensers filled, and towels replaced. Then it all had to be done again. The Louisville Medical Journal was impressed enough to write that hygiene in a Pullman sleeper was better than in nine of 10 American homes.

For most of the Pullman years the porter did one more thing in the smoking room: sleep, or at least try to, on a sofa behind a thin black curtain. It was not easy, on a wafer-thin mattress, with passengers in and out using toilets and cuspidors. Or stopping by to light up cigar or cigarette, maybe staying for a card game and story-telling that could go on ’til dawn. The smoker had long been the most social of rooms in gentlemen’s clubs, a place to catch up and cool down, and that custom thrived on George Pullman’s sleepers. Few noticed the Negro porter trying to sleep behind the screen. Few who did cared. And the company rulebook mandated that “under no circumstances will porter request passengers to vacate smoking-room so that he may retire,” although it did let conductors assign him an empty upper in special circumstances and it reserved the cramped Upper No. 1 berth for him on tourist cars which had no smokers.

But porters crafted a custom of their own to reclaim their bedroom: politely ask everyone to leave the smoking car, explaining you had to clean up and go off duty. “If they didn’t go,” explains retired porter Leroy Graham, “I would come in there with some formaldehyde on the mop. You couldn’t stand it, it burned your eyes and choked you almost.”

Dodges like those did defy George Pullman’s rulebook, but mainly at the edges. “A trainman should, and does, depend more on his judgment than on any set of rules,” wrote pioneering black filmmaker and former porter Oscar Micheaux. “And [he] permits the rule to be stretched now and then to fit circumstances.” A good trainman, or porter, also learned that dexterity, physical and mental, was critical to surviving on the rails. So was the recognition that no matter how taxing the work, it was easier than their fathers’ as slavehands and their neighbors’ in the fields or factories. A sense of humor helped, too, along with an ability to read passengers’ personalities and plenty of patience. “You just gotta haul folks as they come,” said retired porter M. Kincade of St. Louis. “Some’s good, some’s bad, some’s nice and some’s crabby.”

©2004 Larry Tye

Larry Tye, a correspondent for the Boston Globe, examined the lives of Pullman porters during his fellowship year.