In Peru, villagers mobilize against the looters who ransack ancient sites

A lean man in his 50s with skin burnished from a lifetime working in sugar cane fields, Gregorio Becerra remembers the days when his father used to bring home ancient ceramic pots to their home in the village of Úcupe. Birds, faces, fruits, animals — the whole pantheon of ancient Peruvian pottery stood on their living room shelf, where his father would place the perfectly preserved vessels he and his buddies dug up.

“Everyone had a few pots in his house. They were nice decorations,” said Becerra.

But sometime around 1990, all that changed.

“It became a business. Outsiders came. They came from the city, and you’d see them out in the hills digging up everything they could find. They’d take it all away and sell it,” he said.

And so the modern looting industry came to little Úcupe and a hundred villages like it up and down the coast of northern Peru. People who used to excavate pots as backlot hobby or family activity at Holy Week, as much a part of local social life as fishing or football, watched first with bafflement and then anger as professional grave-robbers descended on their lands to search for pieces to supply the exploding international market for Peruvian antiquities. Poor, neglected, marooned by the collapse of sugar prices like boats left by a falling tide, these villages suddenly found themselves living literally on top of a commodity hotter than sugar ever was. They were living on top of ceramics — Moche ceramics from the first millennium A.D. that, for a time, had American and European collectors in their thrall.

Now Becerra is the leader of his village’s grupo de protección arqueológica, known locally as “la grupa,” a citizens’ patrol armed with binoculars, a dirt bike, one revolver and one shotgun but whose most important weapon is the eyes and ears of people living in the adobe homes around Úcupe’s fields and sand dunes. The brigades’ mission is to stop people from plundering the land’s ancient tombs and graveyards. They chase away bands of looters, or they surround them and tie up their wrists with rope until the police come, and they seize their tools — shovels, poles, buckets, and occasionally a freshly dug-up pot or two.

“A month ago I detained three looters and all their tools. We let down our guard for an hour and before we knew it they were digging,” said another leader of the grupa, Gilberto Romero. “It’s like that here. You go to lunch and you come back, and there they are, digging.”

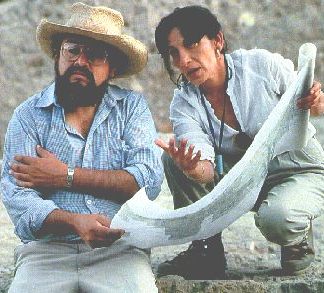

Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva, director of the Royal Tombs of Sipán Museum in the town of Lambayeque, 30 miles north of Úcupe, organized the patrols in the mid-1990s in response to the phenomenal growth of commercial looting in northern Peru. In doing so, he took a cue from rural Peru’s long tradition of ragtag peasant militias known as rondas campesinas that have fought scourges ranging from cattle rustlers to highway bandits to Shining Path guerrillas. This time the enemy was looters hunting for ancient art to supply the global antiquities market. And the spark that lit the art market’s desire for Peruvian antiquities was Alva’s own sensational excavation in 1987 of the Moche tombs from the first millennium A.D. at Sipán, about an hour’s drive away.

So far, the patrols seem to be working, if on a very small scale. A 1,800-year-old Moche burial pyramid, or huaca, stands unmolested less than a mile from the village — a tempting target for looters, who have demolished similar sites less than 20 miles away.

Around the world, from Cambodia to Italy to Mexico, looters are steadily dismantling ancient monuments, burial sites and temples to feed the global collectors’ market. In the process they are destroying our ability to know about the past. When ancient sites are excavated carefully by trained archaeologists, all of humanity can gain an understanding into how those societies lived, how they worshipped, what they valued. Everything we know about ancient life has been gained in this way.

When those sites are ransacked by looters, all that knowledge is lost. All we are left with are random objects that may be beautiful or valuable, but which tell us very little about the people who made them. Looting obliterates the memory of the ancient world and turns its highest artistic creations into decorations, adornments on a shelf, divorced from historical context and ultimately from all meaning.

Looting has been going on for centuries. But with the rise of jet travel and container shipping, never in human history has it been so easy to get looted antiquities to market and never has there been such a wide variety of cultures, styles and periods represented on the market at one time.

In Peru, archaeologists have watched helplessly as looters ransack their study sites. “We excavate by day and the looters come by night,” said archaeologist Sonia Guillen.

With help from local police, a group of researchers led by Alva created anti-looting patrols in Úcupe and other villages scattered around Lambayeque department in the mid-1990s to try to curb the problem on the ground. Eight villages now have brigades, with about 350 people actively involved, and varying degrees of organization and success. Alva calculates the brigades have seized about 3,200 objects, although the goal is not to confiscate the loot. It is to stop looting in the first place.

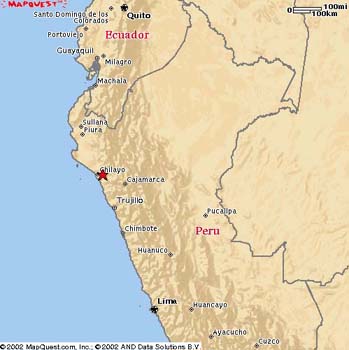

I first visited Úcupe with Alva’s assistant Carlos Wester, who introduced me to village elders, and later visited on my own to see the patrols in action. I took a bus from Chiclayo, a city of half a million people and the commercial hub of northern Peru, through the desert to Úcupe. Romero met me at the busstop and we walked together past the village’s tidy garden plots, adobe homes, and whitewashed church. A man with a gravelly voice and a sleepy smile, Romero’s manner was so mild that I was surprised to learn he doubled as a security guard for the local sugar cooperative and, as such, was licensed to carry a gun. He was the only patrol member who regularly carried a weapon although, he told me, he had never fired in anger at looters. “I’ve fired in the air before to scatter them, but never at a looter. This isn’t a war,” he said. I was glad of that.

Becerra, Romero and I hired a motorcycle that had been fitted with a passenger seat just wide enough for the three of us. The driver took us along a rutted road past fields of spicy red-pepper plants and sugar cane. Now and then Romero would point out a bare hill and explain that it was not a hill. It was another huaca, a pre-Inca burial pyramid weathered by so many centuries of wind and sun that it was indistinguishable from a natural hill.

“We have virgin huacas, never been touched and known only to us,” said Romero, shouting above the sound of the engine. Villagers here see their ancient sites as a potential economic resource that could bring income to the village over the space of years from archaeology or tourism, residents told me. Looting brings income only once, and only for the looter.

The patrols were officially created in this area on July 12, 1994, Romero told me. I had seen a video of that day. Men in cowboy hats and jeans and women in petticoats marched down a street in a mock-military ceremony, carrying banners bearing the name of their town — Pomalca, Zaña, Batán Grande, Úcupe — and the words “Programa de Defensa de los Monumentos Arqueológicos.” Then Alva, sitting with local officials and police at a viewing stand, read the hundreds of assembled villagers a kind of oath of office.

“By your ancestors, do you promise to protect the archaeological monuments under your care?” asked Alva through a megaphone.

“Yes, we promise!” said the crowd.

Cultural preservation is only part of the reason why villagers took so quickly to the patrols. Looters are often seen as an advance-guard for rural bandits or land squatters, people from Chiclayo and other towns who would like to occupy fields around Úcupe and erect houses.

“We have extinguished looting in this area, because after the looters come the cattle-rustlers, the thieves, and the land invaders. All the bad elements,” said Becerra.

Thus Alva and Wester have cleverly used land disputes to create this patrimony police. Yet the pressure remains constant. The patrol has been responsible for the detention of hundreds of looters and land squatters, said Romero, including five the day before I visited. They were still in detention at the police station in the town of Mocupe, five miles south.

“If the police can’t get here fast enough, we detain them ourselves,” said Romero.

The looters are starting to feel the pinch. One professional grave robber known as Rigoberto told me the trade is declining in the north because of stepped up police protection and the anti-looting brigades.

“It’s difficult up there now. You can get arrested,” he said. He and his friends have headed south to the Nazca area, where there are no such patrols, less police interference, and abundant textiles of the kind in demand on the international art market. “We’re finding beautiful textiles, amazing stuff,” Rigoberto told me in Lima recently. He pulled a few samples from his knapsack — tattered swatches of Inca weavings in chocolate-brown and red, a small hint of what Peru’s worst, or perhaps best, looters are bringing to market these days.

If anyone in Peru fears the grupas might become vigilante groups, taking justice in their own hands, no one has yet publicly said so. Yet in Úcupe, residents fear the fight might become more violent.

“Usually they go peacefully but once we detained a group of eight looters who threatened to come back and kill us all. For several days we were under police protection,” said Romero. They shouldn’t have to rely on archaeologists for help, he said. He wanted the police to train and arm them.

©2002 Roger Atwood

Roger Atwood, a longtime correspondent for Reuters, is examining the fate of looted artifacts in Peru.