For every truth you find in India, the opposite is equally true. This well-worn cliché is doubly true when looking at the lives of Indian women. Indira Gandhi’s rule as Prime Minister of India, for example, was a triumph for women in leadership, yet the nation under her rule was populated by hundreds of millions of impoverished women, whose lives changed remarkably little during her term. In the 1990s, India had one of the highest number of international beauty contest winners and one of the lowest rates of female literacy in the world. Maternal mortality rates in some rural areas of India are among the worst in the world, yet India has the world’s largest number of professionally qualified women, with more trained female doctors, surgeons, scientists and professors than the United States.

The legal sphere commands equality, yet the social sphere, where most Indian women live, has remained unchanged despite clear legal and constitutional rights. India’s dominant religion, Hinduism, presents a fundamental duality for women: on the one hand, the woman is fertile and benevolent (the deity Lakshmi — the bestower) on the other hand she is also aggressive and malevolent (the deity Kali-the destroyer.)

This same duality is seen in the mixed blessings that globalization has brought to women in contemporary India. This report highlights the steps forward which Indian women are making, especially in the urban centers in South India. The difficulties that many Indian women face include poverty, female feticide, sexual harassment, lack of education, job skills, HIV infection — especially among the majority of women in rural areas. Though some challenges Indian women face are similar to the struggles of women in the West, most have a uniquely Indian cultural component that makes the challenges worse and the oppression more intense and entrenched.

There is a lack of verifiable current social science research on India. This lack is magnified for women, not surprising in such a traditional and patriarchal society. Similarly, statistics on social problems and poverty are easier to find than research on the comforting social web around women and their extended family network. Defenders of Indian tradition argue that there are fewer pressures on women with respect to “doing it all” as compared to their Western counterparts. Many Indian social workers claim women in India experience less depression and fewer instances of post-natal depression than women in the West, primarily because of this social support structure, the same network that others see as overly oppressive. Non Government Organizations (NGOs) working to develop India, generate reams of statistics on the challenges faced but numbers on the nation’s successes are harder to come by. While much research does exist on the Indian middle class, it is largely funded and utilized by marketers trying to understand consumption patterns.

Globalization has clearly benefited a sector of India’s women. The elite, educated and upper middle class, especially in the cities, have gained by exposure to Western ideas on such issues as women’s roles, career options, and jobs. More Indian women than ever are engaged in business enterprises, international platforms, multi-national careers like advertising and fashion, and have better opportunities because of the free movement of goods, ideas and capital and the improved Indian economy that has been the result of globalization. Indian government statistics also show the unemployment rate for educated women (and men) has declined considerably from the late 1970s to early 1990s.

By many accounts, the business environment in India is more hospitable to women compared to similar developing countries. Men still largely dominate strategic sectors such as policymaking and finance while women fare better in media and advertising. Financial institutions are said to have stricter loan standards for women entrepreneurs while sales jobs requiring fieldwork are often advertised for men only. Despite this adversity, the number of women applying to the prestigious Indian Institutes of Management is growing.

The most wide-reaching mediums of mass communication in India are film and TV, where new ideas are often first encountered. With four times the U.S. population, India has five times as many film viewers in a year. Cinema attendance is disproportionately male while TV viewership (where most films are subse- quently rebroadcast) is disproportionately female as unaccompanied women stay out of theaters to avoid being harassed. The recent advent of government controlled TV, private channels, cable and more recently satellite TV has introduced Indian women, mostly urban, middle and upper class, to an array of both consumer goods and images of other women’s lives. Sponsored TV serials started late in India. In 1985 Hum Log, the first Indian soap opera was broadcast, which was based on a Mexican tele-novella, designed by Mexico’s government to promote family planning.

The mass media tends to reconfirm traditional gender roles, promote unrealistic ideals of chastity, passivity and dependence by women. Some critics charge that movies reinforce male hegemony while blocking women’s development and progress in India. The films often further legitimize abuse of women when scenes of battered or raped women are thrown in gratuitously to spice up movies. But sometimes the same media prompts women to explore new roles. A survey by an Indian weekly magazine revealed that women in big cities use discreetly placed advertisements in newspapers to hire men for afternoons of sexual pleasure, pick up strangers in public places and watch pornographic films in groups. Social scientists say that some Indian women, normally associated with prudence and conservatism, were outgrowing that image, indulging their own sexuality in ways rivaling those found anywhere in the world.

The struggle for women’s equality began in India in the 20th century, as an offshoot of the fight against British colonialism. Western-educated leaders like Mahatma Gandhi initiated this struggle by stating that a woman is completely equal to a man. Millions of women, educated and illiterate, housewives and widows, students and elderly, participated in India’s freedom movement because of Gandhi’s influence. At the same time, women came into their own when they took over for the imprisoned men and expanded the push for independence. In itself, the idea of equality between genders, which derives from Western ideas of individual freedom, was alien to the traditional, family oriented Indian society.

India’s famous female Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, owes her entrance into power to her status as the daughter of India’s founding Prime Minister and heir to the dynastic, Nehru-Gandhi political family line which eventually gave India three prime ministers. She downplayed her pioneering role as a woman in politics by saying, “I do not regard myself as a woman. I regard myself as a person with a job.” The percentage of women in the parliament in India is currently 9 percent, down from a peak of 10 percent in 1988. By comparison, women make up 14 percent of the representatives in the U.S. Congress.

The Western feminist movement of the 70s and the simultaneous media boom brought another wave of change to Indian feminism. The emergence of formal feminist networks is new, but informal women’s networks for sharing, learning and socializing have long existed. Radical protests in India were few and anti-feminist protests arose in India, continuing until 1985, where some women argued that Indian women were not oppressed and were happy as wives and mothers. Much of modern Indian feminist activities bypassed the majority of India’s women, those living in rural areas, ending up aiding mostly middle-class, urban women.

Historically, Indian women enjoyed a social status unparalleled in human history according to the most widely accepted interpretation of ancient Hindu texts. The Indian dancer Mallika Sarabhai put it this way: “Hinduism is the only philosophy in the world where the woman does not come out of the man.” Despite such a widely held egalitarian belief, in traditional Hindu culture of today only women and untouchables (the lowest caste) are forbidden to know, hear or read the Vedas, the sacred Hindu texts. Women are denied an equal share of inheritance because in most families, only the sons inherit the wealth of the parents, as married girls are no longer considered part of the family. Similarly, only a son can continue the family line or perform the funeral rites that ensure the soul of the dead’s safe passage through the Hindu purgatory.

Ancient rites are still performed over pregnant women in traditional households to elicit the birth of a male and magically hope to change the sex of the unborn if it happens to be female. Although dowries were officially banned in India in 1968, they are still pervasive through private negotiations between families. While sons bring dowries to their parents, daughters are seen as a burden because they require dowries in order to be married, sometimes placing their parents, particularly in the middle and lower classes in debt.

For these and other reasons, some feminists see the Indian family as the most oppressive institution, because women’s roles are defined solely in terms of others. The traditional roles for women are the child, adolescent, wife, daughter-in-law, mother, mother-in-law, and widow. At marriage, a woman often loses her identity and is referred to by her own parents as the “son-in-law’s wife.” In other sectors of Indian society, women change their first and last names to that of their husbands, obliterating their identity and sealing the husband’s feudal-like ownership of his wife.

The rare act of divorce is seen as a reflection on the woman, who is viewed as Westernized, amoral and unmindful of her duties as a good Indian woman and wife. The growth in the number of divorces in India is seen as either a sign of demoralization of Indians or as a sign of self-assertion and independence.

Widows who make up more than 60 percent of the women over the age of 60 rarely remarry and live out their lives in a culture that often shuns them as bad luck. Widows are supposed to remain celibate, wear white, curb any romantic impulses, not wear the Bindi on their forehead and deny themselves pleasures to honor their dead husbands while widowers can remarry freely, often to child brides.

Typical of the dichotomy in Indian women’s lives is the fact that prostitutes are both scorned and sought. Poverty and domestic desertion are major factors contributing to women entering prostitution. The so-called Devadasi belt, in central/southern India, is the home of organized criminal networks trafficking in young women. Devadasi means “maid or servant of god,” referring to the ancient practice among communities in India of dedicating their daughters to the service of a temple deity. The girl is “married” to the goddess and has to earn her living by dancing and singing in praise of the goddess. Although the custom is now illegal, girls who are dedicated to the deity when very young are often sold into prostitution. According to research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the incidence of HIV infection has risen in female prostitutes from less than 10 percent in 1990 to between 40 percent and 50 percent in a 1996 survey of Mumbai (formerly Bombay) and other cities. The survey found a 14 percent HIV incidence among women who are not prostitutes, which was disturbingly high given their low-risk behavior. These women erroneously believe themselves to be at low risk because of their presumed “monogamous” marriages.

Indian culture discourages communication between men and women regarding sexual behavior and promotes fidelity after marriage for both sexes, particularly for the woman. Arranged marriages based on astrological signs and family traits rather than individual personalities are the norm for the majority of couples. Love marriages, where the individuals select their own spouse, are still rare and premarital sex, while a mark of distinction for men, is a badge of shame for women.

Indian women’s social status improves immensely within her extended family once she is pregnant and bears children (preferably male). A mother who cannot produce boys is considered deficient or even damned. “Better to be mud than a barren woman” goes one proverb. Although biologically untrue, it is considered the mother’s fault if a daughter is born and the father’s triumph if it is a boy. Girls are seen as only temporarily a part of their own families because they move to the groom’s family upon marriage, depriving the girl’s family of income and leaving her parents with no one to look after them as they age. Also, when girls marry, dowries further cement the belief that a girl is a lifelong burden. Similar beliefs are held in emigrant communities of South Asians, most notably among Indian-Americans. A small percentage of Indians travelling to America on family visits exploit America’s relaxed laws on abortion and terminate unwanted (reportedly disproportionately) female fetuses while away from home thus avoiding Indian familial, social and even legal issues.

Despite a constitutional prohibition outlawing sex determination tests in 1994, amniocentesis and more recently ultrasound are regularly used for gender determination and resulting female feticide. One in ten children in India do not live to age one. The number is worse for girls, who are innately stronger as babies — but are more likely to be deprived of food and medical care. UNICEF documents show that one fourth of the 12 million girls born in India do not survive to see their 15th birthday, and one-third of these deaths occur before their first birthday. Nearly 50 million women are missing from the Indian population. The continuous decline in female/male ratio since 1901, has resulted in a national ratio of 927 women for 1,000 men, the worst ratio among the ten most populous countries in the world. In the state of Punjab, the ratio is 793 women to 1,000 men, arguably the worst in India. In Rajasthan, the ratio is so skewed that some women marry one man and indirectly the man’s brothers. The extended set of pseudo-husbands do much of the traditional housework while the woman is obligated to satisfy the sexual demands of her husband and his brothers.

Despite explicit legal prohibitions, child marriage is still prevalent especially in North India, where 75 percent of rural marriages involve brides under 18. The average age of a Hindu bride is 15 to 16. Tradition holds that girls should be married soon after her first menstrual period, allegedly to guard against promiscuity. Women 15 to 29 years old have more than three-fourths of the children born in India. Illiterate women are estimated to have four children while women with at least high school education have only 2.2 children each, close to the number of 2.1, the target for stabilizing the population. Currently, India has one of the highest birth rates in the world, with a nationwide average of 3.4 children per woman in her lifetime. This number is a tremendous decline from the average of 5.9 in 1960.

Since 1970, the use of modern contraceptive methods has risen from about 10 percent to 40 percent. The use varies widely by state, from a high of 53 percent in Maharashtra to a low of 20 percent in Uttar Pradesh. The most striking aspect of contraceptive use in India is the predominance of sterilization, which accounts for more than 85 percent of total modern contraceptive use. Female sterilization, though physiologically much more difficult and risky, accounts for 90 percent of the sterilizations. Mortality rates reach as high as 500 per 100,000 sterilization operations, a grim symbol of how medical standards have been lowered to meet the government’s sterilization targets. Since the legalization of abortion in India in 1971, the reported number of legal procedures has reached an estimated 600,000 annually. However, other estimates suggest that at least twice as many illegal (and unsafe) abortions take place in unlicensed clinics.

Indian streets are largely male-dominated so unwanted touching and harassment of women in public places, known as Eve teasing, is common, including groping on crowded buses, pressing up against women on streets and unwelcome touching in movie theaters. North Indian men are particularly renown for their disregard of women’s rights, and it is on the plains of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar that Indian women are often subject to physical (and verbal) harassment if wearing modern Western garb, which is considered provocative.

Wife beating is perhaps the most prevalent form of violence against Indian women, occurring in as much as 50 percent of families across India. Indian men who one minute worship Hindu goddesses and the next beat their wives depend on Hindu fatalism to ensure submission, because a woman’s fate is supposedly set at birth and so nothing can change that destiny. Surveys reveal that not bearing a child, especially a son, were major causes of violence. Attitudes towards domestic violence, especially among women, are startling. Among literate women, 63 percent found some justifications for wife beating, while among illiterate women it is 76 percent.

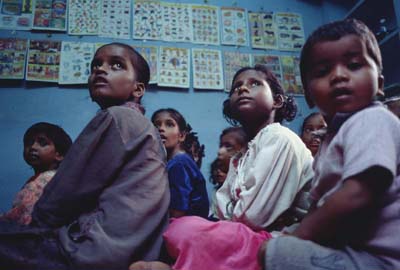

The Indian women who suffer the most are the indigenous peoples, known as “tribals.” Despite four and a half decades of constitutional protection, they remain the most backward ethnic group in India on the three most important indicators of development: health, education and income. Tribal women’s lives are characterized by over-work, illiteracy, sub-human physical living conditions, high fertility and malnutrition. India’s population of 68 million tribals is the largest indigenous population in the world. The literacy rate of rural tribal women is below 13 percent, the lowest of all groups in India. The school dropout rate for tribals at the secondary level is as high as 87 percent and for girls it is almost 90 percent. Consequently, there is a negligible amount (0.06 percent) of tribal women in colleges and universities.

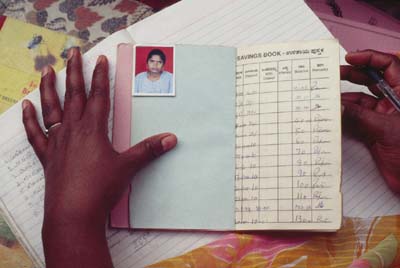

The traditions of India, which are focused strongly on the extended family, contrast dramatically with the individualism and the nuclear family of the West. Building on this tradition of women’s focus on families may be a way to make life better for India’s women according to development agencies. They see women as the real agents for change because their research shows that raising a woman’s income through training, education and micro-credit lending raises household income. Women spend their extra money on their families while men spend it on liquor or cigarettes.

Clearly, women’s issues are India’s issues, from the growth of HIV infection to improving family income, from abortions for sex selection to micro-credit for entrepreneurs. To neglect women is not only inequitable, it is immoral, wasteful and will vastly diminish what could be India’s otherwise bright future.

©2002 David H. Wells

David H. Wells, a freelance photographer from Providence, RI, is spending his Patterson year documenting India.