India, a country stereotyped for its vast number of poor, also is home to what many consider to be the world’s largest middle class. The very size and population of India tends to obscure everything else about the country. For example, India, a nation stereotyped as famine stricken, last was devastated by a famine in 1943, before independence, when India was still ruled by the British. When the British finally left India in 1947, they fled a partitioned country wracked by war and dislocation. They also left behind the rule of law, democracy, an independent judiciary, a free press, railways, canals, and harbors. They introduced modern education and helped create a small middle class.

Historically, India had a quarter of the world’s trade in textiles and more than a fifth of the world’s wealth in 1700. It was the leading manufacturing country (handloom textiles and handicrafts) in the world in the early eighteenth century. Before the industrial revolution, India had a 23% share of the world’s GDP and a 25% share of the global trade in textiles. By 1990, despite having one sixth of the world’s population, it saw its share of world income decline to below 5 % and less than 1/2% of world trade. Economic growth shrunk from 7.7% a year between 1951 and 1965 to 4% between 1966 and 1980 as India withdrew further from world trade and raised tariffs and taxes, becoming one of the worst-performing developing economies.

India’s Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao resolved in 1991 to bring India’s economy into the 21st century by introducing reforms that attracted foreign investment. He liberalized the economy by reducing the federal deficit and cutting inflation. India began embracing a free-market economy after four decades of state planning. Since the economic reforms of 1991, parts of India have rapidly moved from poverty to prosperity and much of the nation has emerged as a vigorous free-market democracy. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, India now ranks as one of the ten largest emerging markets in the world.

To many, the most striking feature of contemporary India is the explosion of its new middle class. Full of energy and drive, the Indian middle class is said to be uninhibited and pragmatic.

Unlike the older bourgeoisie, which was traditional, secular and ambiguous, the new middle class is first and foremost street savvy. The new middle class has worked hard to rise from the bottom, bringing with it a nouveau-rich mentality that some Indians consider vulgar.

The first dilemma in looking at the Indian middle class is defining it. Simply converting living costs from Indian Rupees (RS) to dollars is one sure way to misunderstand the economics of life in India. One aid is the National Council of Applied Economic Research’s mid-1990’s report on the growing Indian middle class. It was based on a national population that was estimated to be 900 million rather than today’s 1.1 billion. The survey said the Very Rich consisted of about 6 million (or 67/100 of 1 %). Below them were three sub classes: The Consuming class, about 150 million people (17%,) the Climbers, about 275 million people (30 %); and the Aspirants, about 275 million (30 %). Beneath these were the Destitute, estimated to be 210 million (23%).

The Consuming class was reported to have an annual income between $1,300 and $6,000, and typically owned a TV, cassette recorder, pressure cooker, ceiling fan, bicycle, and wristwatch. Two-thirds of them own a scooter, color TV, electric iron, blender, and sewing machine, but less than half of them own a refrigerator. India is now the world’s largest market for blenders and the second largest for scooters (after China). Sixty percent of all urban homes have TV sets and 68 million of all Indian homes have TV sets. More than 32 million of those have cable, growing 8% a year. By comparison, only 22 million homes have telephones.

An Indian once was said to have arrived in the middle class when he wore something on his feet. This is no longer true as even the lower classes now wear PVC sandals. Today’s distinctive class marker is housing. Homes of brick and cement are preferred. The Consuming class is expected to triple in ten years, reaching 450 million people by 2010.

At the birth of independent India 54 years ago, the Indian middle class was a small and insignificant minority, less than 10% of the population. Today, India’s middle class is one of the largest in the world, equal in some estimates to the population of the United States. Despite India’s size, its trade with the U.S. is small. By comparison, American trade with China and its 1.2 billion people is vastly larger than that with India and its 1.1 billion. U.S. businesses sell $3.5 billion worth of goods a year to India but sell more than $11 billion to China. Similarly, Americans annually buy only $6 billion worth of goods from India compared to more than $50 billion from China.

The economic reforms started in the early 1990’s have spurred an annual growth rate exceeding 7%, with especially rapid growth in the middle class. Projecting that growth rate into the future, India’s income will double every ten years. Within a generation almost 50% of India’s people could become middle class and poverty could diminish to 15%. In line with this growth, the Indian middle class is developing an appetite for telephones, cars, televisions, clothes, refrigerators and other consumer goods. This new Indian class is filled with entrepreneurs and consumers who follow a very Western pop culture.

The homelands of India’s new middle classes are the more than 200 cities with a population of over 100,000 filled with people who no longer look to the distant metropolises of Bombay or New Delhi. Rural prosperity also is growing slowly, reaching villagers who are 74% of India’s population of one billion.

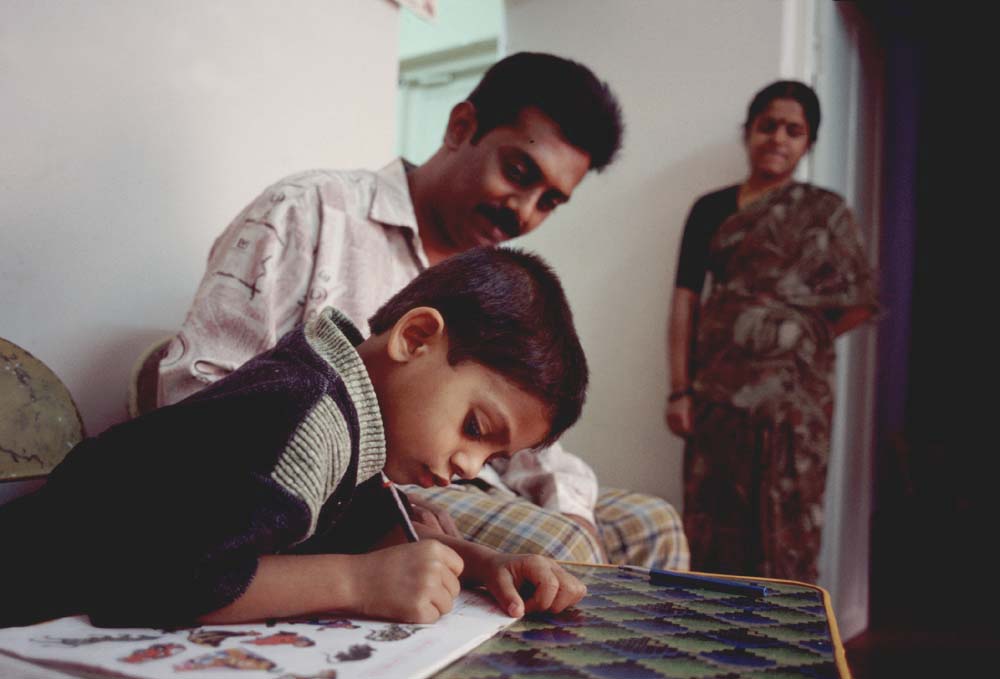

A recent India Today poll of middle class Indians found striking similarities with middle class attitudes across the world. These Indians rank travel and outdoor enjoyment as their top interests. They are concerned about crime, inflation, unemployment and especially education, which they see as the key to upward mobility. India sends about six times more people to universities and other higher educational institutions as compared to China. Ironically, roughly half of India is illiterate, while China’s adult literacy rate is closer to 80%.

Bangalore, where much of this article is focused, is the capital of the southern state of Karnataka. It is the most Anglicized and middle class city in India. In the 1950’s, it became an established center of government sponsored scientific research. Since the 1970’s, it has experienced rapid growth based on professional and technical skills, not the traditional sources of wealth in India, which was the control of land or industry. Bangalore’s software exports have soared, growing from $50 million to $6.3 billion in less than a decade, accounting for 11.5% of India’s total exports. India has become the world’s premier supplier of skilled software engineers.

Despite the boom that many Indians are enjoying, the benefits are trickling slowly, especially to those in the countryside. In the densely populated farms and villages of the north Indian “Hindi belt” (along the Ganges River) the economic boom is much less visible than in urban centers. Some estimate that 300 million Indians live in poverty, more than the population of the United States. By one estimate, India’s annual per-capita income is a mere $1,910, trailing even neighboring Bangladesh and well behind China’s $4,050. Similarly, 53% of all Indian children below the age of five are malnourished compared to Ethiopia’s 48%.

Rising out of a nation of one billion, India’s middle class is considered by many to be its last potential savior. Though hard to define statistically, its work ethic and focus on upward mobility may spread the benefits of economic growth across the country. The fixation on education, a universal route up the class ladder, may succeed where Nehru’s socialism and central planning have failed.

But even spreading education will be an uphill battle in such a vast nation. India has the largest number of illiterates in the world, an amazing 290 million, more than the combined population of the U.S. and Canada. Because India is at the forefront of information technology and education is needed to maintain that position, national policy and individual family decisions focused on education may indeed lead India to a better-educated and wealthier future.

©2001 David H. Wells

David H. Wells, a freelance photographer from Providence, RI, is spending his Patterson year documenting India.