I never thought I would ever want to return to Dalbandin, a little desert town of some five thousand people in the Pakistani province of Balochistan. It is one of the least memorable places I have ever been, situated uncomfortably in the middle of nowhere. It has mud-baked streets and a teeming bazaar, and clusters of tiny mud houses that are dwarfed by the soaring minarets of a white marble mosque, which had been built a number of years ago by the Saudi Arabian Defense Minister, Prince Sultan. The town’s economy is based on grazing and smuggling, and every man seems to be armed. Dalbandinians are outnumbered by Afghan refugees two to one.

The Government Guesthouse where I stayed, during a December visit a few years ago, is a low-slung building with peeling green walls and a concrete floor, covered here and there by straw mats. There was no heat, and it was freezing cold. There was no running water, no electricity, no coffee, no butter, no herbal tea. “But if we are fortunate, Madam, we may have a few hours of electricity tonight,” the caretaker of the unfortunate building, Rahim Bux, told me as soon as I arrived. He explained that Dalbandin had no electricity; the town’s center operated on generators provided by the provincial government and by Prince Sultan. “But the Saudi generators stopped working after a year,” he said. “And the government generators never worked at all.”

Now, as I sat in the falcon market in Doha, the capital of the tiny but strategic Persian Gulf emirate of Qatar, a falconer whom I happened to meet by chance said to me, “The problem, Madam, the real problem is in Dalbandin.”

It was early January, and Dalbandin, even though it was just across the Strait of Hormuz, seemed very far away. But it was connected to Qatar in two very symbolic ways: the U.S. war in Afghanistan, including the bombing campaign, was being assisted here as it was being assisted there. Every morning, at precisely five o’clock, American warplanes roared over Doha Bay — and over my hotel — giant birds, with wings outstretched, carrying their lethal cargo of bombs. The other link that connected Qatar and Pakistan was a more esoteric one: and it, too, involved a bird.

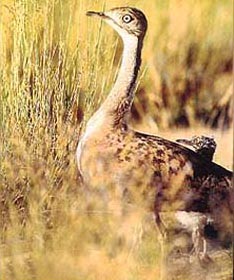

Indeed, I had come to Dalbandin in search of the houbara bustard, an endangered species of a fast-flying and cursorial desert bird that migrates to Pakistan each autumn — via Afghanistan and Iran — from the former Soviet Union and from the Central Asian steppes. But the year I came, and this year, too, the bird was late, again — causing any number of crises for the Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

For it was the Foreign Ministry that awarded dozens of special permits to Arab dignitaries to hunt the bird each year, despite the fact that Pakistanis have been prohibited from killing the houbara since 1972. Yet each season, which lasts from November until March, their countryside is carved up, like a giant salami into ever smaller parts. Some sheikhs — among them the Saudi Minister of Defense — receive permits that cover thousands of square miles. No other hunters may cross the invisible line that separates Prince Sultan’s personal hunting grounds from those of, for example, Sheikh Zayed al-Nahayan, the President of the United Arab Emirates, or the Dubai leader, Sheikh Maktoum. At least, in principle, that is the rule.

Many Pakistanis are puzzled by the royal hunts, and can’t really explain why, with the arrival of the houbara, scores of Middle Eastern potentates — Presidents, ambassadors, ministers, generals, governors — descend upon their country in fleets of private plans. They come armed with computers and radar, hundreds of servants and other staff, customized weapons, and priceless falcons, which are used to hunt the bird. But then the houbara bustard has been a fascination to the great sheikhs of the desert for hundreds of years.

By the 1960s, it had been hunted almost to extinction in the Middle East. The kings, sheikhs, and princes hurriedly dispatched scouting parties abroad. They recruited British and French scientists to attempt to breed the houbara in captivity. But none of their endeavors solved their most pressing problem: Where could they hunt the houbara bustard now?

Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and North Africa seemed the most promising hunting grounds. But the sheikhs quarreled with Colonel Qaddafi, and he forbade them to come to Libya to hunt; they quarreled even more strongly with the Iranian mullahs, who, in a sweeping proclamation, banned the houbara hunts. So did the government of Tunisia. Egypt was more accommodating, but the houbara population had been severely reduced there, too. Afghanistan had an abundance of houbara, but then the Soviet Army invaded, and the ardently anti-Soviet Persian Gulf sheikhs simply refused to deal with the Communist infidel. Only Pakistan and Morocco — and, to a lesser extent, Algeria — remained as preferred hunting grounds.

Now, in the falcon market in Doha, as we sat in a large circle in overstuffed armchairs, bringing a traditional majlis to mind, and sipped cups of sugary tea, the shop’s owner went to a large, rectangular plot which was covered with sand, and retrieved a hooded saker which is used in the houbara hunts. He brought it to us for inspection: the bird perched nobly, upright on his arm. As the morning progressed, and he and other trainers passed by us one by one, all with priceless falcons on their arms, I remembered something that Dr. Mohammed Hasan Rizvi, a leading Pakistani eye surgeon and conservationist, had told me about the royal houbara hunts during an earlier trip toPakistan.

Since Dr. Rizvi was said to be extremely close to the sheikhs, I had asked him why the houbara bustard was of such fascination to them.

“It’s the contest between the houbara and the falcon,” he’d replied. “The fascination is in the flight; it can go on for miles. The falcon is the fastest bird on earth, and the houbara is also fast, both on the ground and in the air. It is also a clever, wary bird, with a number of tricks. The sheikhs fall apart when they see the houbara. They follow the bird helter-skelter in their customized cars — brand new Mercedes 250s is what they used to bring. I hunted with the then Crown Prince (now the ruler) Sheikh Maktoum of Dubai. Within twenty minutes, our muffler broke off. Even with a vehicle that the Sheikh had had so carefully customized — it had special springs and shock absorbers, and higher, heavy tires — a Mercedes is not meant for the desert, and we traveled like a tank.” He paused for a moment, and then he said, “In the old days, it was so much more refined. You would see their caravans for miles along the roads, and the roads were perfumed. King Khalid. Prince Naif. Sheikh Rashid. They were real falconers.”

He paused for a moment, and then he went on, “All their falcons have names. They’re named either for great Arab heroes or famous falcons of the past. Some years ago, when I went out with one of the sheikhs, his favorite falcon was lost. He sat for four days in the middle of his camp, calling out his falcon’s name. Can you imagine? This was the president of a country, and he did nothing but sit and shout ‘Mubarak’ into the wilderness.”

Thinking of Dr. Rizvi, I couldn’t help but recall a feudal landlord I’d met at a lavish dinner in Karachi for one of the visiting sheikhs a few years before. He, too, had been fascinated by the royal houbara hunts and had told me then, “They’re the craziest thing I’ve ever seen, but they’re like a religion to the sheikhs. They’re out in the desert from dawn to dusk, covered with dirt and dust. The driver is submerged in one of those jeeps, as if he were in an A.P.C. The sheikh sits next to him in an elevated seat that swivels at a hundred and eighty degrees. I guess it’s a good hobby, if you’re into that kind of thing.”

“What kind of thing?” I asked him.

He looked somewhat startled, then said, “My lady, these Arabs eat the houbara for sexual purposes — they think it’s an aphrodisiac!”

As I pondered the mysterious ways of the desert, I puzzled over why the falconer I had met earlier in the day had been so distressed about what was happening in Dalbandin. The main thing I could remember about it was that it was the closest town, thirty-five miles away, from a place called Yak Much, which then, and now, was the Saudi Defense Minister’s personal hunting ground. As a result, the Saudi royal hunters–who usually hunted two to three thousand birds during their monthlong stay–had given the residents of Dalbandin two generators (which, of course, didn’t work), a mosque (which they didn’t need), and an airport (which was used almost exclusively by the hunters themselves — exclusively, that is, until this year’s season by which time the government of Pakistan had granted the U.S. military sole use of it.)

And this, of course, was the falconer’s major cause of distress. For, with the American bombing of Afghanistan, Dalbandin and its sleepy airport had been jolted alive. There was a constant din as B-52 bombers, C-130 transports, and KC-10 air refueling planes landed and took off from the airfield’s runways, which sprawled for forty-five hundred feet. U.S. military men came and went from its low-slung terminal. The town’s smugglers were apoplectic. The guesthouse was full. And royal hunters throughout the Persian Gulf were furious.

For despite the sheikhs’ support (in principle that is) for the U.S war in Afghanistan, they were not at all convinced that the bombing should originate from one of their own private, hunting airfields. And even though the airport in Dalbandin had been built originally by the British, during the Second World War, it had been expanded and modernized by the Saudi Defense Minister Prince Sultan, not to accommodate the war in Afghanistan, but to accommodate the Saudi royal hunters, whose numbers had increased over recent years, as had the number of houbara they bagged and shipped back to the kingdom, in specially designed refrigerated trucks, aboard C-130s, which had been reconfigured expressly for the houbara hunts.

Yet now, at the very time that the houbara should be arriving in Pakistan, its numbers had been dramatically reduced. And, despite contrary claims of conservationists, many sheikhs were convinced that the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan had disoriented it.

©2003 Mary Anne Weaver

Mary Anne Weaver, a correspondent for The New Yorker, examined the politics of Pakistan during her fellowship year.