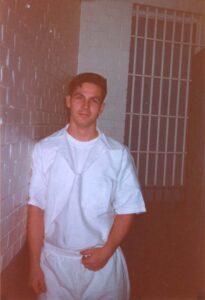

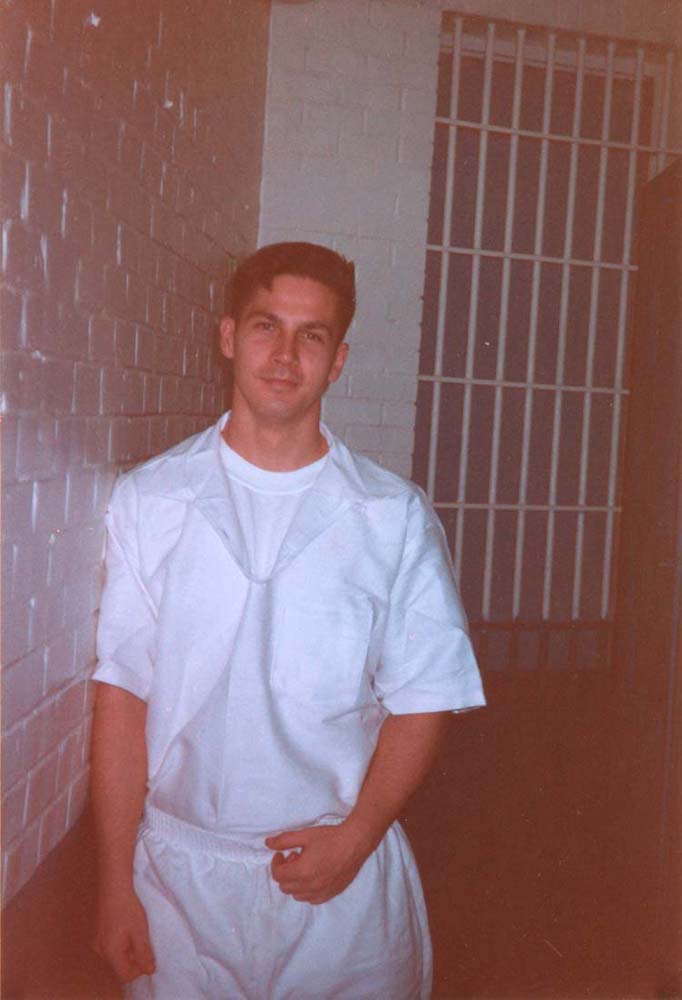

Jon Christopher Buice doesn’t look the part of a gay-bashing killer. Sitting behind a blue steel mesh in bleached white prison garb and T-shirt, the brown-eyed, baby-faced convict, even at 26, could pass still for the ordinary white suburban teenager he once was.

Buice is serving the seventh year of a 45-year sentence for the July 1991 slaying of Paul Broussard, who was himself 26 when he was bludgeoned and stabbed to death by Buice and nine of his friends on a Houston street. Even today, Buice seems unsure how he ended up behind bars, a ward of the Texas Department of Corrections in Huntsville, about an hour drive due north of the city where the murder occurred.

“Everything is still a blur to me,” he says in a voice so soft it is nearly lost in the din of iron bars opening and slamming. “I think about it every day, but I’m still not sure why everything happened the way it did. I’m not sure I’ll ever know.”

Along the gruesome trail of antigay violence in America, the Broussard murder remains an unusual episode. Years before such crimes were deemed national news, this brutal attack led to significant changes in the Houston police department, including a sting operation aimed at nabbing young gay bashers in the act. It was so effective that several undercover officers posing as gay men were assaulted.

The attack also galvanized the city’s cautious gay community, which at the time was reeling from AIDS and the 1986 repeal of an ordinance meant to shield gays from discrimination. It changed forever the trajectories of the ten young men charged in the crime as well as the lives of Broussard’s family and friends, transforming them from anguished supporters of their loved ones to determined gay rights activists.

That fateful Fourth of July evening began like the usual weekend binge for Buice and his friends. After two days of drinking and partying, the ten young men–all but one attending Woodlands High, a largely middle-class school about half way between Houston and Huntsville–piled into three cars and headed into the big city. The band stopped first at an abandoned grain elevator, a popular teen hangout, where they painted graffiti and loafed in its cavernous confines.

Already in an alcohol and LSD-induced haze, Buice could feel the tension building. He recalls his friends’ penchant for climbing onto the old structure’s rafters. “I remember thinking, ‘Somebody’s going to fall and get killed.’” According to Ray Hill, a Houston activist who traced events prior to the crime and led the gay community’s response, Buice and his friends “spent a couple of hours running around like mice in a treadmill. Then they wanted more action.”

The quest for riskier thrills sent the teens careening toward trouble. Led by the oldest among them, 23-year-old Brian Spake, the men piled back into their cars and headed to Montrose, a heavily gay neighborhood, for a teen male ritual that was gaining in popularity among the suburban set: hassling, harassing and occasionally assaulting homosexual men.

According to police, it was not the first time many of the youths, and others like them, had taken part. The Houston gay and lesbian community had complained about the abuse to the police department for years with no result. In fact, Montrose was considered a kind of nocturnal playground. Westheimer Street, a major artery bisecting Montrose, was generally clogged on weekend nights with teenagers cruising the streets in their cars. When they grew bored of sitting in traffic jams, they would park and head toward a thriving circle of gay bars, cafés and restaurants looking for targets to vent their frustration.

Despite being under the legal drinking age of 18, Buice remembers hanging out in both gay and non-gay bars in the area. “I know it’s probably hard to understand, but I didn’t hate gay people,” he says. “I had gay friends. I had gay relatives. I’d gone to gay bars with them. I’d go to straight bars. It didn’t really make any difference to me. If a guy hit on me, I’d just say, ‘Hey, man, that’s not my thing.’ Some of my best friendships started that way.”

Yet there is no getting around the anti-gay MO of Buice’s behavior that night–or his role in the killing. As he and his friends drove around Montrose, they began homing in on gay men. Spotting someone they believed adhered to their stereotype of a homosexual, they shouted–delighting in the bad pun–”Where’s Heaven?” a reference to a popular gay dance club in the heart of the neighborhood. If the person would point to the bar or give them directions–confirmation in their minds that he was gay–they shouted slurs and made threatening gestures. According to police, several men were accosted in the same manner that evening before the pack converged on Broussard.

By that point, the young men had gotten away with their activity for several hours and, as Hill puts it, “They were smelling blood.” Just after the 2 a.m. closing of a bar near Heaven, they came across Broussard and two of his young friends. They were walking toward home, just blocks away. With only a few years separating victims and perpetrators, in another circumstance, as Buice now acknowledges, the young men actually might have been friends. But for Buice and his collaborators, at least on this night, sexual orientation was the ultimate dividing line, the personification of “other.” It was what drew them together across their own boundaries. Four of the young men involved in the incident were Latino; one was black; and the other six white. In the racially charged culture of Texas teenagers, homophobia gave them common cause.

After an angry exchange of words, several of the boys began chasing Broussard and his friends. Broussard headed into a dead-end road while his friends escaped down a busier street. Soon he was surrounded. One of the boys–it is not clear who–wielded a two-by-four with nails protruding from the end. Broussard struggled mightily, landing blows on Buice and the others. But he was soon overcome with exhaustion and the pummeling of fists and puncture wounds. As he lay dying, blood poured onto the pavement from a chest wound Buice had inflicted with his Buck knife–evidence that eventually led to the long sentence received by many of the men involved in the killing. Paul Broussard died on a hospital bed a few hours later.

Thousands of young men waste away in Texas prisons, sentenced for everything from drug possession to rape and murder. But rarely do these young perpetrators find themselves in the middle of a morality play about the very definition–and progressive redefinition–of right and wrong, good and evil. Rarely are they in a position to offer insight into the circumstances of a serious social problem.

On one level, Buice is a singular character. In an April 1999 open letter addressed to the radio station KPFT, Buice wrote that to “the gay and lesbian community I owe a momentous apology. A repentance for an act of atrocity. The night of July 4, 1991, haunts me every day. It has hurt me deep inside. I was involved in taking a man’s life. If it were possible, I would sacrifice my own life to bring Paul back. But this is not conceivable. And I aspire that you will hear the cries of who I am today.

“As I’ve grown older,” the letter continued, “I have gained a more relative understanding of what took place that night in Houston. It was never my intention to harm anyone. Never could I possibly imagine I would take a human life or take part in any action which would inflict fatal injuries. But the fact remains: I did participate and I have taken responsibility for this. Of course I knew I was wrong. In my youth I made poor decisions. After years here in prison, I see how disruptive my life and attitudes were.”

Buice says he wrote the letter after hearing about the murder of gay student Matthew Shepard, from the University of Wyoming. Through television coverage of that killing and others like it, Buice said in the letter that he learned of “some hateful actions taken against the minority of…a different sexual orientation. This wounds my heart and I’m appalled to know that I, too, was involved in this type of action.”

Yet as eloquent and sincere as the letter appears, Buice often seems at a loss to explain the crime and the motive behind it. He simply can’t reconcile his professed lack of antipathy for gay men with his attack on one.

It doesn’t help that Buice claims he “blacked out” the night of the incident. He remembers someone shouting, “Where’s Heaven?” at passersby. His next recollection is he is in the car driving home, his clothing stained with Broussard’s blood. It wasn’t until he heard about the murder the next day that it dawned on him what he had done. “I was drinking and tripping on LSD,” he says. “I probably could have done anything that night and not completely realized it.”

As for the inducement for the crime, he says that at least in his case, it had less to do with Broussard’s sexual orientation than with the fact that the boys were sure they could get away with it. They viewed Montrose, with its burgeoning gay community and thriving nightlife, as a sort of lawless enclave, freed of the enormous social strictures of their everyday life in school and in their suburban homes, where their every move seemed monitored by teachers and parents. The sex lives of gay men appeared exotic and forbidden. That held an unmistakable allure, even if some of the boys expressed a fierce loathing for it. They had heard on the streets that police didn’t care about hassling gays, who they also believed were likely to carry more cash, have more fashionable clothing, and were extremely unlikely to report incidents to authorities.

It was a combustible mix–alcohol, drugs, male bonding and the odd combination of fear and loathing the boys felt about homosexuality. “There was a thrill-seeking aspect to it,” Buice says, borrowing a term from a researcher who had interviewed him about the crime just days earlier. “It was something we could do together and get away with it. It was really more about our relationships and our sense of boredom than about the victim. It could really have been anybody. It just happened to be Paul.”

Buice says that the crime was not premeditated. “I can say for sure that none of the guys were killers,” he says. “We never once talked about getting anyone. In my wildest dreams I could never imagine that I’d come home with blood on my hands that night. It was just something that sort of happened. A lot of things went wrong all at once.”

There is no doubt Buice has an ulterior motive in expressing remorse. He is eligible for parole in 2003, though it is highly unlikely that he will receive it, even though by all accounts he is a model inmate. He is studying for a college degree, and would like to pursue graduate courses in psychology, in part to help him “come to terms with my past and to help others.”

But, there is also the distinct possibility that he is completely sincere. He clearly likes the idea of making restitution to those who have suffered from his crime. He agreed to this interview only after I mailed him a copy of an earlier article I’d written about another young man who was convicted of a similar crime. It was titled, “A Gay-Bashing Killer Turns His Life Around.”

Upon meeting me for the first time, he commented that he would like that headline to be his life story. In the open letter–one of the few ever penned by a confessed gay basher–Buice offered help the gay community. He can’t explain what form that help would take, but he suggested that by telling his story he might prevent others from making “the same mistake I have.”

Buice has convinced at least one important critic. Hill, himself a former prison inmate who has befriended Buice in the years since the murder, declared that it was evident that Buice had seen the error of his ways, that he had been punished enough, and that he should be given serious consideration for parole. “The question is whether you see the criminal justice system as a means of retribution or rehabilitation,” Hill says. “If you look at it in terms of rehabilitation, there is little question that Jon is now ready to be a good citizen.”

The person who matters most in Buice’s quest for early parole is having none of it. For nearly a decade, Nancy Rodriques has battled the demons that swirl around the murder of her son, Paul Broussard, her first of three children by two husbands. She asks herself whether she was accepting enough when Paul came out to her not long before his death. She regrets not being able to comfort him after the beating and stabbing, when he was talking incoherently at the hospital. Even today, she often wakes up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat.

Rodriques lives on the outskirts of Macon, Georgia, where she earns a living selling tires. She spends most of her time outside work tending to her two grown children, David and Michele, and her grandson, Jalen, 4. She hopes to take Jalen to a lesbian minister at the local Unitarian Universalist Church for a lesson on homophobia. “I want Jalen to know that it’s okay for some boys to love other boys, and for girls to love other girls. I want him to be completely free of the ugliness surrounding Paul.”

She has focused most of her still simmering anger on the ten boys and in combating their efforts to win early release. She has testified at parole hearings, lobbied state legislators, spoken at hate crimes rallies, and toured the prisons where her son’s killers are locked up. Because the perpetrators were given sentences ranging from parole to seven years to 45, depending on their level of involvement in the actual assault, she has faced the possibility that one of her son’s killers will be released nearly every year since they were incarcerated. In March, one such perpetrator was in fact released. “My goal in life is to live long enough to make sure that Buice serves his full term,” says the fifty-six-year-old. “That would make me 87–I think I can make it.”

When it comes to gay bashers, she has reason to be suspicious about Texas justice. Just five years before Broussard’s death, Dallas Judge Jack Hampton had gone easy on an eighteen-year-old who with a pal had shot to death two gay men on the grounds that “prostitutes and gays [are] at about the same level. I’d be hard put to give somebody life for killing a prostitute.”

In Texas at least, it seemed kids could simply claim that perpetrators had made a pass at them and then get away with murder. At every parole hearing for one of her son’s perpetrators, she remains vigilant of even the most subtle suggestion that her son was somehow less than fully human. She believes he is deserving of the same protection and justice as everyone else.

Between drags on a cigarette, Rodriques struggles to contain her sorrow and fury. “I have good days and bad days,” she says. “Paul was my firstborn and we had a very intense attachment.” On her desk in her modest home lies an envelope with the autopsy reports and photographs from the murder scene. Nine years after the murder, she still refuses to look at them. She has set up an elaborate system so that she never has to see them. When they are required as evidence in a parole hearing, she has a friend make copies and place them in another envelope so she can mail them. “I can face almost anything but that,” she says. “It may sound silly, but that’s where I draw the line.

“I just couldn’t bear to see what those boys did to Paul. As far as I’m concerned, there is no way they can ever pay enough of a price for what they have done to my boy.”

©2001 Chris Bull

Chris Bull, the Washington correspondent for The Advocate, is examining violence against gays during his Patterson year.