I look like a witch. Tumpa has painted my eyes thick with kohl, my lips bright pink, my toenails vibrant blue. During this daily ritual my mother calls long distance from England on my mobile phone. “How is everything darling?” “Fine, everything’s fine,” I answer. I wince while Tumpa yanks my hair into shape. My mother doesn’t know I’m living in a brothel. Tumpa’s mother doesn’t know she’s living in a brothel either. Brothels are inherently places of deceit.

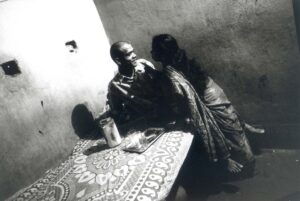

I have a mobile phone for my safety. Tumpa constantly uses it to call her lover Gautam, to find out when he is coming over. Gautam is a 26-year-old assassin. He tells me that his father was killed by political goondas (hooligans) just before he was born in 1974 and he wants revenge. Gautam claims to have killed eleven people so far, but he is aiming for the seventeen involved in his father’s killing. I ask him if he will stop at seventeen. He says he doesn’t know.

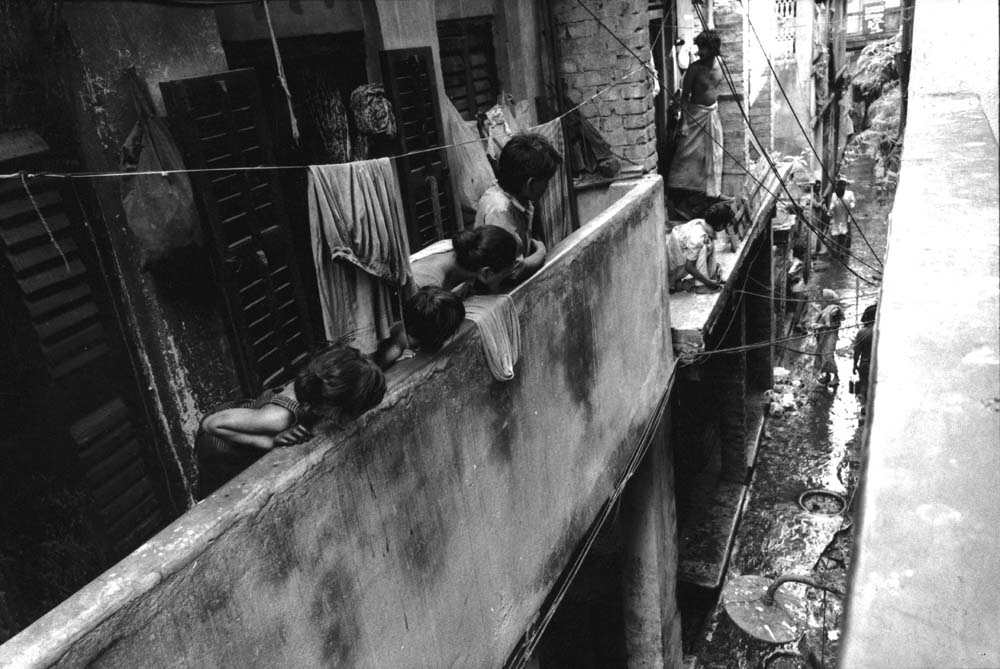

Tumpa has one year for every man Gautam wants to kill. Born in Bangladesh, she was married to a man she didn’t know at age eleven and bore a son, Raja, at age thirteen. Her husband drank and abused her. One night he poured kerosene on her and the baby and tried to set them on fire, a common form of domestic violence in India. Tumpa escaped and took her son back to her mother’s house. She stayed there but Tumpa’s mother could not support them on her maidservant’s salary of 600 rupees ($15.00) a month . A neighbor, Deepa, introduced Tumpa to prostitution. Tumpa makes the rough twelve hour bus journey home every month or so to visit her son and her mother. She tells her mother that she earns a living working in a light-bulb factory. She knows that if she gave all her earnings to her mother, she would become suspicious. So Tumpa saves money for her son’s future.

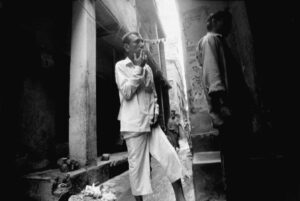

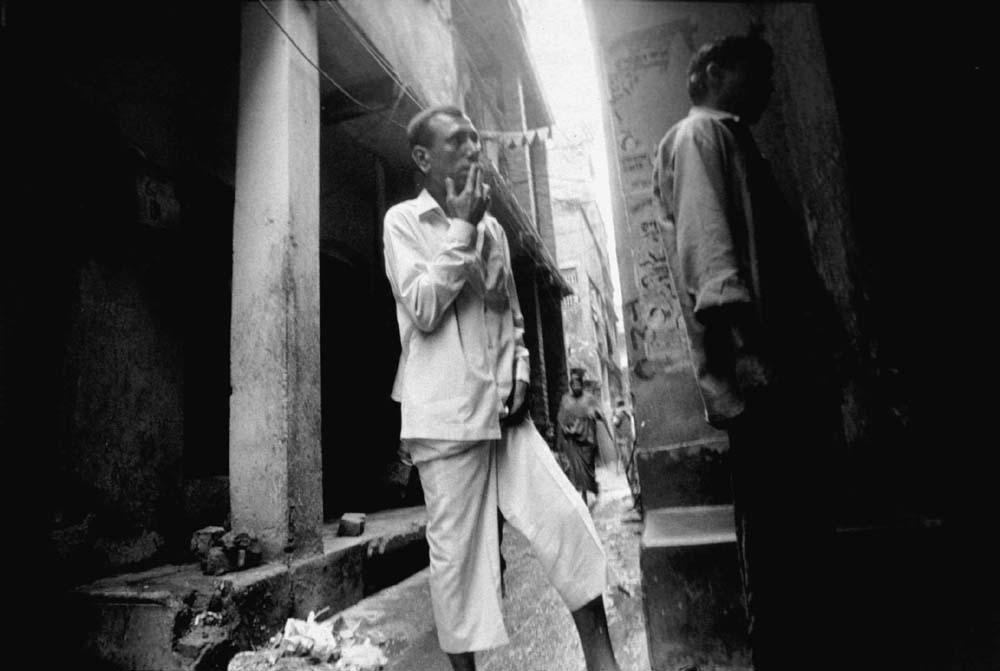

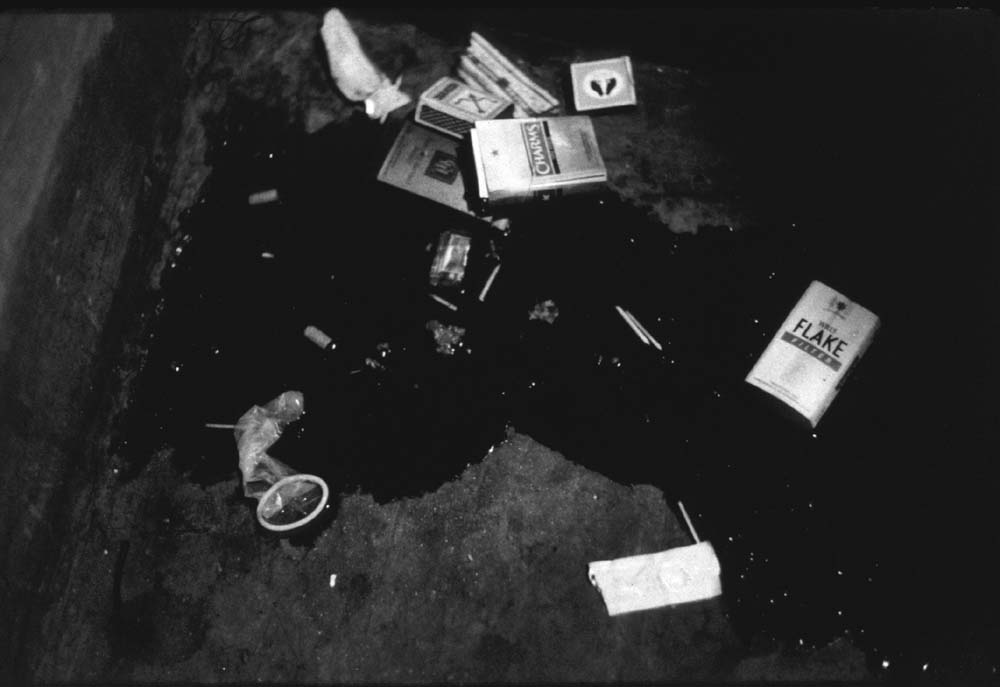

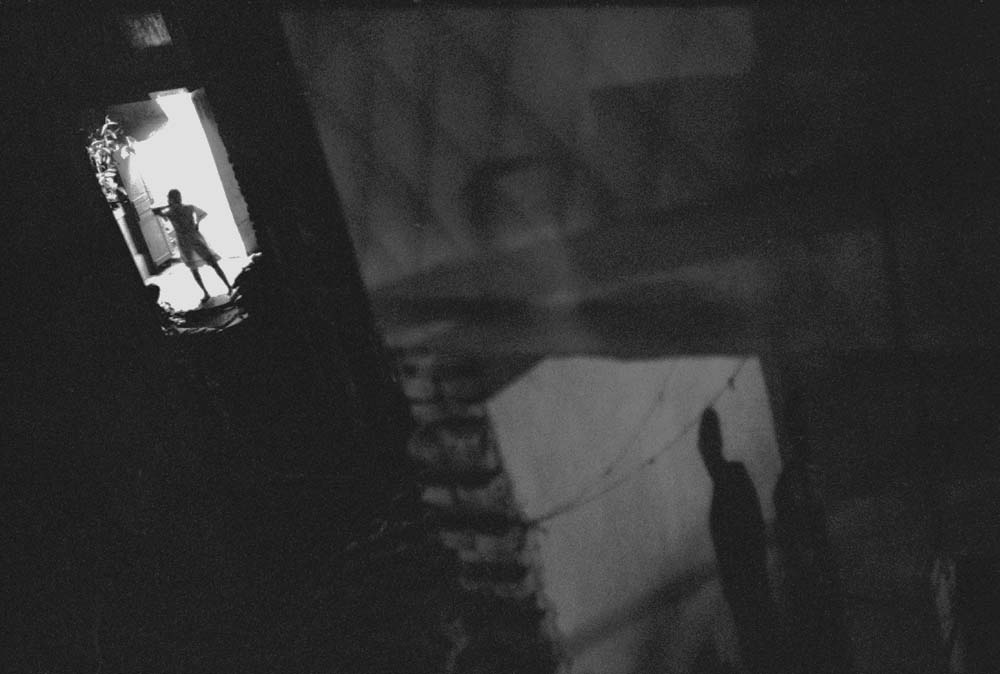

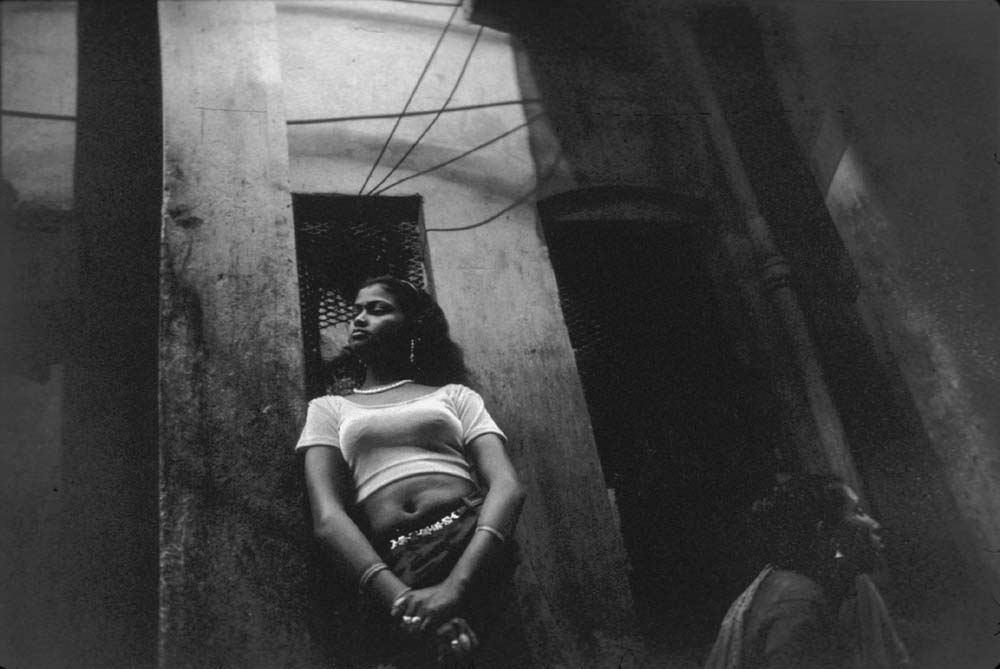

Tumpa and I spend hours sitting in the lane outside the brothel. She looks gorgeous in her pale yellow sari and delicate sandals, a lotus blooming in a cesspit. A rat pokes its head out of the hole behind the mound of garbage in the middle of the lane. I am fascinated by the garbage. It is so ordinary – old rice, vegetable peelings, egg shells – yet so particular – used condoms, medicine wrappers, torn underwear. A mangy dog waits for the rat to appear. A prostitute hits the dog with her sandal and he runs away yelping. Customers come and go.

Tumpa disappears upstairs with a man and is back in five minutes. She puts the money in a little purse which she slips into her bra. She smiles mischievously and says, “This is bank!” Tumpa speaks almost no English and I speak almost no Bangla, but somehow we manage to communicate.

A customer old enough to be her grandfather approaches her and asks how much. She says 60 rupees ($1.50). He shakes his head and moves on. I tell her she should ask for one lakh ($2,500) and she throws her head back and laughs. Tumpa is always laughing. We watch a drunk man stumble by. We look at each other. I say “BADMASH!” (bad man). She says “VERRRY BAD!”. We laugh.

I love Tumpa. She’s proud and feisty and sweet. I tell her I’m going to take her to America. She shakes her head and cries, “No, no, my son!” I tell her I’m going to take her anyway. She grabs my baseball cap and puts it on backwards. “Next time,” she says, and hums a Hindi film song.

©2002 Zana Briski

Zana Briski is a freelance photographer in New York City, spending her Patterson year documenting female and child sex workers in Calcutta, India.