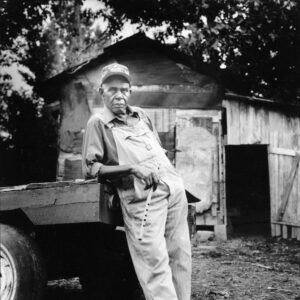

On a small, nondescript farm in rural northeast Mississippi, between the towns of Senatobia and Como, is one of America’s last and most tangible links to its African musical past.

It’s here, at country picnics in the community of Gravel Springs, that 92-year-old Otha Turner still performs on the homemade cane fife as younger family members beat out African-based rhythms on drums, and members of the local community gather to dance, drink corn whiskey, and eat goat sandwiches just as they have for well over a century.

Otha Turner, known by friends as “Gabe,” heads the last African-American fife and drum band in a region that once supported more than a dozen. And like the archangel of the same name, when Otha blows his instrument, it’s a rallying cry linking the community to its ancestors. Dancers yell, “Blow it, Gabe” as they encircle Otha and his drummers, moving in harmony to the hypnotic rhythm of the drums as parts of a larger organism.

African-American fife and drum music can be traced back to British and early American military music. Thomas Jefferson’s personal body servant even organized a small band to help rally the revolutionary war effort. But in the hands of slaves and their progeny, the stiff, formalized music used to direct military movements was transformed by the same African syncopations and poly-rhythms that eventually gave birth to jazz and blues.

In a time when drumming by slaves was strictly forbidden for fear of illicit communication, the fife and drum was an acceptable outlet, even used by confederate armies during the civil war.

Today, the fife and drum music performed by the Turner family has more in common with the music of West Africa than the Spirit of ’76. These musical ties are reinforced by the dancers, who “salute” the drums with pelvic movements not unlike traditional dances still seen in Africa, Haiti and the West Indies.

Folklorist Alan Lomax, who was the first to record fife and drum music in 1942, considers it one of his greatest discoveries in a lifetime of research. In his 1993 book, “Land Where the Blues Began,” he wrote: “in vaudou ceremonies, dancers make pelvic gestures toward the drum to honor the holy music that is inspiring them. I never expected to see this African behavior in the hills of Mississippi, just a few miles south of Memphis.”

When asked about the origin of the fife and drum, Otha Turner replies “How old it is? I don’t know. They said it’s African, back in African times, that’s what they say, I don’t know, I wasn’t thought of. And they say drums was a-calling. If a person ceased, and you carry them to the cemetery, loaded in the wagon, all them drums get behind them and marched, just like it was a hearse, and they brought them to the cemetery, playing the drums.”

In the North Mississippi hill country of Tate, Panola and Marshall counties, the traditional venue for fife and drum music was the summer weekend picnic. Following an afternoon baseball game, fife and drum and black string band music was performed late into the night. Rural blacks heard the drums from miles away and were directed by the sound, arriving by foot or wagon.

Annie Faulkner of Abbeville remembers when her father Lonnie Young played: “If [daddy] was playing somewhere close around, like this time of evening [dusk], when he hit that drum we could hear it from our porch from across the river over there, a long ways away.”

Dr. Sylvester Oliver, an ethnomusicologist from Rust College in nearby Holly Springs, sees the drums as the historic cultural centerpiece of Hill Country music. “I have interviewed several elderly individuals who told me…they would not start their picnic unless the drums came and kind of sanctified the area. They always wanted the drums to come and bless the area.”

Today, the picnics held on Turner’s farm in late summer and early fall are the last link to that tradition. The picnic begins with the slaughter of one or more goats early in the day that will be barbecued and served as $3.00 sandwiches along with beer and soft drinks, sold from Otha’s picnic stand. People begin arriving at dusk as Otha, followed by two snares and a bass drum, begin performing the “Shimmy She Wobble”, (a standard fife and drum tune named for the type of dancing it often inspires), and snake their way slowly across the farm lot usually inhabited by chickens, dogs, horses and goats.

In his younger days Otha could play for hours without stopping as dancers kicked up clouds of dust late into the night. Now in his nineties, he allows himself frequent breaks and augments the picnic entertainment with performances by local blues musicians like “Rule” Burnside, R.L. Boyce and Luther Dickinson. In the last few years, he’s also brought in a DJ to provide music for the younger crowd. But the focus of the picnic is, as it has always been, the drums.

Otha’s daughter, Berniece Turner Pratcher, still plays drums for her father and remembers the picnics of her youth. “Back then you could hear fife and drum pretty much whenever you got ready too,” says Pratcher. “The picnics died out as the people died out. My daddy is about the only one who still has a picnic.”

Annie Faulkner recalls attending picnics where her family’s fife and drum band played: “The picnics that I went to, it was exciting. People would be kicking up dust. They’d be down on the ground. Kicking that dust, have dust flying. Both feet would be white with dust.”

Otha Turner learned the fife by observing older local players like John

Bowden, who used to perform at picnics when Turner was a teen-ager.

“He’d get on that fife man, it’d get late over in the evening, folks was running, hollering, ‘Blow it ,John,’” recalls Turner. “That son of a gun would get to blowing, kept his cap sideways, and I’d be walking along behind him, that son of a bitch would blow it for them.”

Bowden, who at age 95 is the oldest known living fife player in the state, has long since retired from playing, but still recalls his glory years. “It’s all gone,” recalls Bowden. “Used to be a good time in them days. I didn’t want to miss nothing. I’d hear a drum hit, and man I just, Whew!, I’d have a fit.”

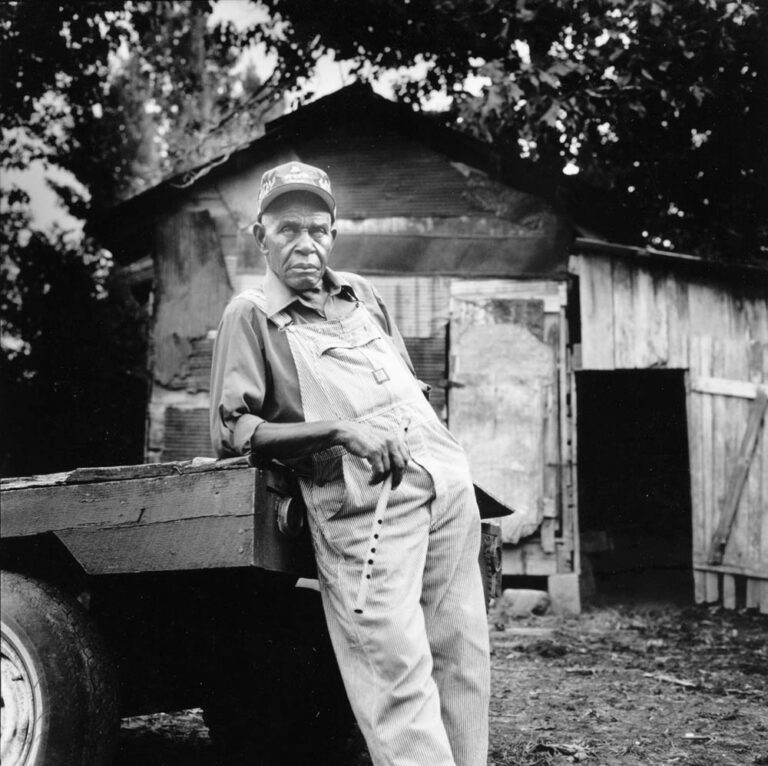

Turner acquired his first fife from a neighbor, R.E. Williams, when he was a teen-ager. “He was out there to the lot feeding his hogs,” says Turner. “Fife in his pocket, he’d pull it out, he’d walk around there and blow, standing around and look at the hogs, he’d walk and blow.

“I said ‘Mama!’ [She said] ‘What?’ ‘I hear that man blowing that thing, I want to go up there mama.’ She said ‘All right young man, I tell you what, I’m gonna let you go up there a little while and don’t you stay long. Don’t let me to meet you.’ I went flying, I run every step up there, I had to go.

“‘Mr R.E.!’ He looked around, ‘What?’ I said ‘What is that you blowing?’ He said ‘That’s a fife son.’ I said ‘A Fife?’ He said ‘yeah.’ Well I thought a fife was a dog. I said, ‘Mr R.E., will you make me one of them things?’ He said, ‘If you be smart and industrious and obey your mama and do what she tell you, I’ll make you one.’

“About a month after that he called me, handed it to me, said ‘Here’s your fife’ I said ‘THANK YOU! THANK YOU!’ I said, ‘What’s the price?’ He said, ‘You don’t owe me nothing.’ I said, ‘I sure do thank you.’

“He said, ‘You ain’t going to blow it’. I said, ‘I’m gonna try’. He said, ‘That’s the best words you spoke, don’t nothing make a fail but a try, son.’ He said, ‘If you try and want to blow it, you gonna blow it, but if you never try, you never will blow it.’”

The sound of his early musical attempts annoyed his mother, so he was forced to practice on the sly. But his persistence eventually paid off.

![As Otha Turner’s grandson K.K. Freeman takes a turn with his grandfather’s fife during a late-summer picnic, a local woman known as "Hanah" shows her appreciation of the music by dancing up to the musicians. As the music plays on with increasing intensity, dancers are often inspired to "salute" the drums with pelvic gestures or perform similar motions while prone to the ground, not unlike drum dances of Africa and the West Indies. Otha Turner says the musicians and dancers feed off each other’s energy. "Them drums rolling, make you feel good," says Turner. "I get out there behind [the drums] and cut a step, that interest the next fella. He gonna jump right out there like me. ‘Come ON!’ We get together. That’s an encouragement."](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Steber_African06-768x775.jpg)

“When I learned how to note that cane, I said, ‘I got it now!’” recalls Turner. “I learned it good. Sometimes I’d walk, going to visit somebody at night, I’d blow my cane all the way over there and back. [People] would hear it, ‘Man, you sure was blowing that fife last night.’”

His reputation got him jobs at picnics playing for men like George “Pump” Toney, and Will Edwards, who ran a racehorse track and provided barbecue and music for his guests.

It was at these gatherings earlier in the century that the fife and drum often alternated with a now-defunct musical form that equally characterized the unique music of the Hill Country: the black string band. These bands performed ballads, reels and old-time music on instruments like the fiddle, mandolin, banjo, string bass and guitar —playing in a style that many now think of as exclusively white in origin. Ironic, considering one of the primary instruments of white folk music, the banjo, is an entirely African-derived instrument.

Little is known about these early bands, since few recordings exist from the period, but Dr. Sylvester Oliver notes that the location of the Mississippi hill country helped create a unique regional mixture of “Southern Appalachian culture and the Mississippi Delta” within the black string band tradition.

Black hill country string bands played for white as well as black audiences all over the region, at movie houses, formal gatherings and private parties until their commercial potential was diminished by the Jim Crow laws of the ’20s and ’30s, according to Oliver.

Perhaps the best known of these musicians was Sid Hemphill, who was born in 1878 and was the master of nine instruments, but was primarily known locally as a hot fiddle player. Hemphill was recorded by the Library of Congress in 1942 and again in 1959 performing ballads, break-downs, and fife and drum music: a cross section of 19th century black folk music pre-dating the blues. Most surprising was Hemphill’s performances on the “quills,” an ancient instrument heretofore unknown in black folk music with ties, according to Lomax, to Romania, ancient Greece, South America the Pygmies of Africa.

Sid’s granddaughter, famed female Hill country blues guitarist Jessie Mae Hemphill, remembers a time when “country music” had a decidedly darker hue. “That white guy what play that fiddle about ‘Turkey in the Straw,’ all of that come from my granddaddy,” says Hemphill. “Wasn’t no white band playing nothing like that. What they playing now, all that come from my granddaddy.”

And just as blues from the Delta gave birth to rock and roll, the music of the North Mississippi Hill Country predates the Delta blues.

Dr. Oliver notes that the rhythms and percussive drive of fife and drum music had a “strong influence” on the development of Hill Country blues guitar, since most early bands performed fife and drum, string band music and/or blues —depending on the occasion and desire of the audience.

The most famous guitarist typifying Hill country blues was Fred McDowell, who, beginning in the ’60s, often left his home in Como to play festivals where he became the darling of the blues and folk revival circuit. But Oliver considers the late David “Junior” Kimbrough to be “the last bastion of what Hill music was all about from a Folk perspective.”

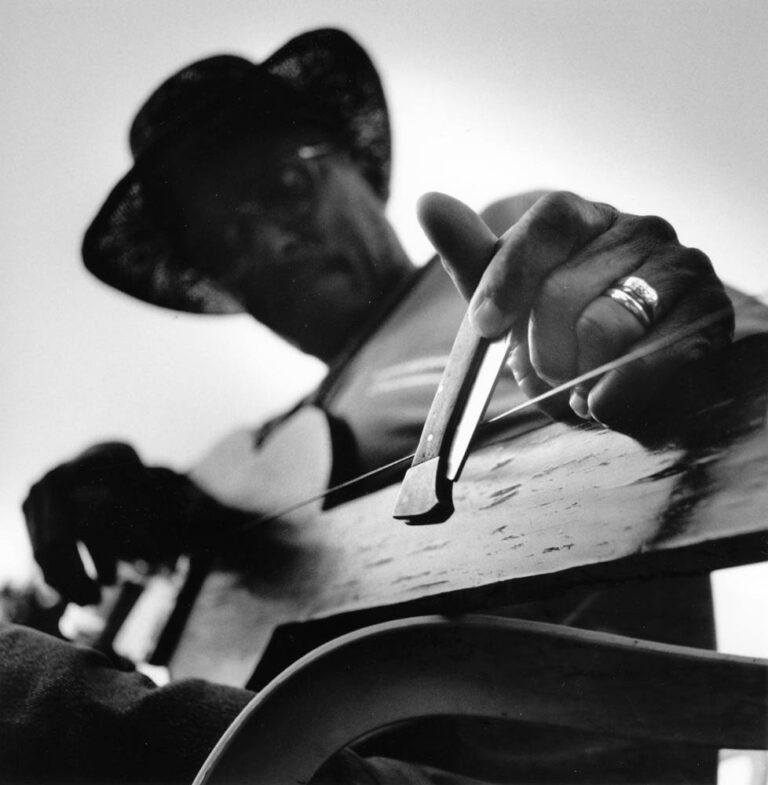

Kimbrough, who died in January of 1998, was a social and cultural institution in Marshall County. His house parties, and later his juke joint on Highway 4, provided the central gathering place for many blacks in the extended Hill country community since the late 1950’s. He personally trained, or at least influenced, most blues musicians in the Marshall County area, including the late rockabilly legend Charlie Feathers, whom he taught to play guitar.

“[Junior] was like a magnet,” says Oliver. “It was his university. He could draw musicians young and old. He didn’t do a whole lot of talking with them but he would allow them to experiment. He would allow them to add their uniqueness to whatever he was doing.”

And the complexity of what he was doing was often difficult to follow. Junior’s son and long-time drummer Kinney Kimbrough remembers “It took me a long time to learn how to feel his music. He played his bass line and his rhythm all at the same time. See, other bands have their changes every 6 bars or so, but daddy [would] have his changes, this one on 3 bars, next time on 10, this time on 1 or 3. See, you have to know him, you have to feel him to know how to play with him.”

Junior adapted hill country traditions into his own original compositions and style of playing that had a profound effect in the area. And like the fife and drum, Kimbrough’s music had a propulsive, hypnotic quality that inspired people to dance. As he played songs like “All Night Long” and “You Better Run” with repeating guitar riffs, a song could stretch on for a half hour as dozens of bodies moved as one in the stifling summer heat of his country juke joint.

“People loved the rhythm of his music,” remembers Kinney Kimbrough. “It makes them move. You know it’s like a hill country funk blues or something.”

Despite Junior’s death, Kinney still opens his father’s juke joint every Sunday night for crowds that have hardly diminished. “I really kept it open because I know how many people loved him,” says Kimbrough. “And I know that that’s the only way that they can feel kind of close to him. Some think of the place as their home away from home. It makes them feel good.”

Junior’s music lives on through Kinney and his brother David Kimbrough Jr., who combines his father’s guitar sound with modern influences, but can play “Junior” like no one else. “It’s just by the grace of God that I inherited playing music with my brother David,” says Kinney, “So we could keep it going.”

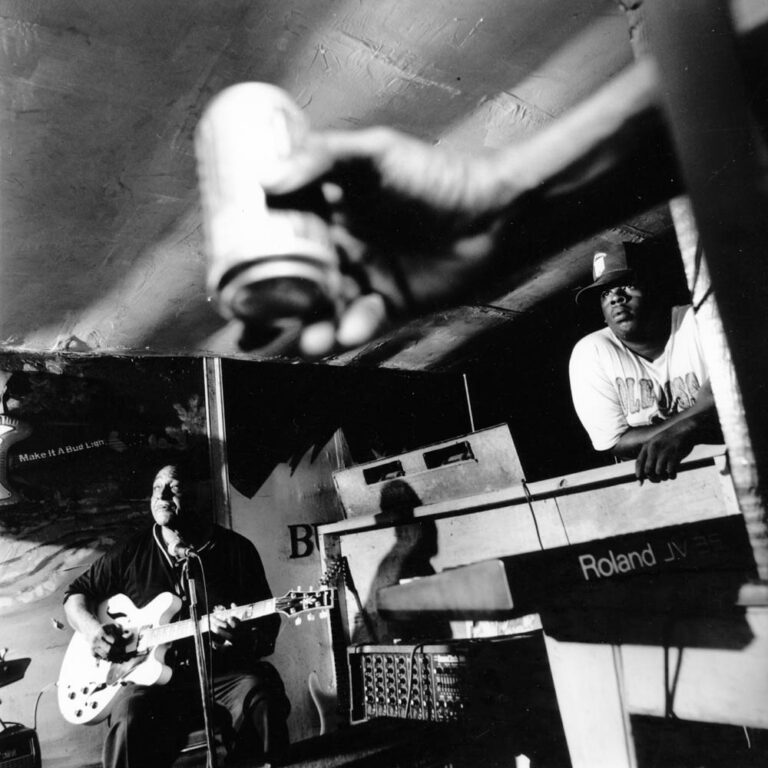

Junior Kimbrough’s longtime friend and music partner R.L. Burnside still plays at the club on Sundays when he’s not on tour across America or Europe promoting his latest album. Both Burnside and Kimbrough have become hill country blues phenomena over the last five years on the strength of critically acclaimed releases on the Oxford, Miss., blues label Fat Possum.

Kimbrough’s first Fat Possum release, “All Night Long,” was the recipient of a rare five-star (classic) album review in Rolling Stone magazine. In 1996, he did a two-week tour opening shows for punk/shock-rocker Iggy Pop.

Burnside, who first recorded his traditional hill country blues in 1967 for the Arhoolie label, has achieved even greater success in the wake of collaborative musical efforts with post-punk noise rocker Jon Spencer of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion and tours opening for acts like the Beastie Boys.

But similar to collaborations in the ’60s of African-American blues men like Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters and various British and American rockers, the results do more to increase the bluesman’s name recognition and earning power than for creating memorable (or even listenable) music.

“I didn’t like it when I first heard it,” says Burnside of his latest Fat Possum release featuring dance remixes of his powerful, grungy hill country blues. “I thought it was coming out just like we did it, you know. And then it come out remixed. I didn’t like it. But it’s selling.”

Burnside’s music, though marked by the same propulsive, repetitive rhythms that distinguish hill country guitar, is a link between this tradition and post-war blues sound of John Lee Hooker and Lightning Hopkins.

Burnside learned guitar from Hill country musicians like Ranie Burnette, Son Hibler and Fred McDowell, but he spent his formative years going to the picnics where fife and drum music was performed.

When asked if fife and drum music influenced his playing, Burnside responds: “Yeah, I think it did. A lot of people say that the blues sounds like fife and drum music. All the blues, they say, started from fife and drum bands.”

If Burnside’s music, like Junior Kimbrough’s, lives on, it will be through the musical efforts of his sons, especially DeWayne Burnside, who plays in a style closest to his father’s.

But what of the mother of all Hill Country music, fife and drum? Who will evoke the spirit of Pan and inspire future lines of drummers to musical abandon? Who will keep the centuries-old tradition alive?

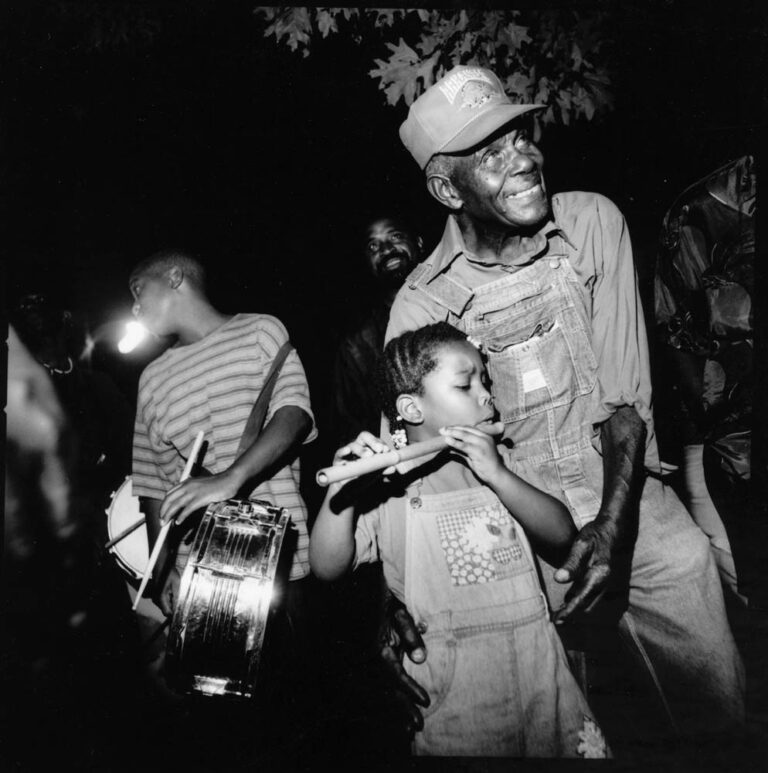

Most folks in the Gravel Springs community put their hope in the hands of Otha’s precocious 8-year-old granddaughter Sharde, who made her musical debut at age 5 and continues to be the highlight of every picnic.

“Sharde’s gonna be good,” beams Otha, “She just needs somebody to keep pushing her, be with her, boost her up.”

On the night of the picnic, everyone is waiting for Sharde to perform and they crowd around as she hits her first tentative notes on the fife to let the drummers know she’s ready. As the snares begin their roll and the bass drum drops in, she leads the drummers with a seriousness and confidence that belies her 3-and-a-half-foot frame.

After playing a few phrases on the fife with authority, she breaks down into a dance that causes the crowd to erupt into cheers, laughter and shouts of encouragement. Her grandfather, Otha, stands close by, his hand hovering near her shoulder, a look of utter joy on his usually stern face for the first time tonight.

“Take your time,” he calls to her, “Blow that thing!” She magically coaxes notes from her primitive cane fife that cut through the shouts and drum rhythms into the night air. All eyes are on her, but she is unshaken by the attention. She feels her grandfather’s presence and is buoyed by his gentle encouragement. “Take your time.”

When she blows her final notes and raises her fife into the air, counting out the final three beats of the song to end the drums, the crowd exhales a cathartic cheer. Someone emerges and embraces her. Adults laugh loudly and slap each other on the back, “That little girl is something else!”

Otha beams quietly, watching his granddaughter receive her praise with grace, confident in the knowledge that his legacy is in good hands.

©1999 Bill Steber

Bill Steber, a photographer for the Nashville Tennessean, is illustrating the blues in Mississippi.