“I believe I’ll get drunk, tear this barrel house down.”

—Drunken Barrel House Blues, Memphis Minnie.

The juke joints are dying.

“We used to have big crowds, every Friday night especially, and check nights,” said James Alford, manager of Smitty’s Red Top Lounge in Clarksdale, Miss.

“But [now] it’s not like that… The casinos have affected this place terribly.”

Casinos, home to the gambling that Mississippi legalized six years ago, are also home to free music, free drinks and free food.

To a juke joint business already fighting a slow death from more modern entertainment competition, the casinos are accelerating their demise.

Perry Payton runs the Flowing Fountain Lounge in Greenville, Miss.: “Right now…I play a band here, I have to charge at least $15. Tyrone [Davis] played [at the casino] and it was free. I think Little Milton was $5. Lynn White was free.”

Payton says his business has fallen off 65 percent to 70 percent since the arrival of riverboat gambling.

“As long as you play the machines and give away liquor, you can’t compete with that, you know.”

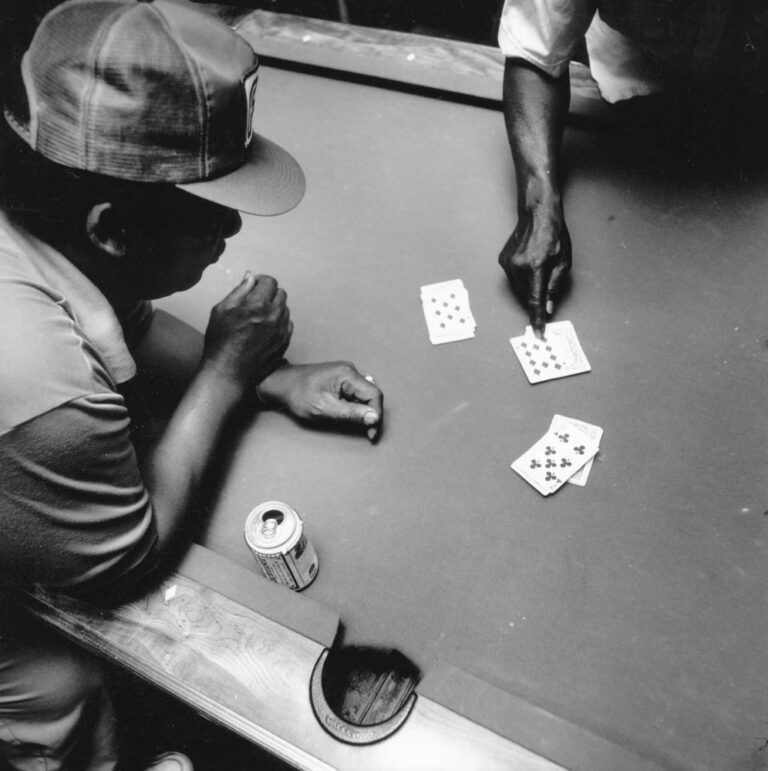

Even the traditional juke-joint back room gambling has taken a back seat to glitzy corporate casinos.

They’ve “stopped that business. Done stopped that,” says Chester Johnson of Dublin, Miss. “They don’t look for no crap games and card games now… Everybody be going [to the casinos] now.

“Yeah, that casino got everything they near about wanted. They got them games and whiskey too up there, you know, them drinks… They got the crowd now.”

For most of this century, the Delta had as many country jukes and blues joints as it did churches.

Casey George, a former professional gambler from Dublin, Miss., remembers a time when “just about every house you pass near abouts, everybody [having a party].”

The rural weekend establishments were usually run by a local bootlegger or by someone selling his product. They provided musical entertainment in homes or in abandoned sharecropper houses as a means of selling food and corn liquor for profit.

Juke joints also contributed to the formation of one of this country’s most enduring and important cultural legacies: the blues. If the Mississippi Delta was the cultural crucible that birthed the blues, then the juke joint was the kiln where the musical fires burned brightest.

For black Delta sharecroppers, isolated by a lack of transportation, they were a social outlet and a “pressure valve” to vent the week’s stress.

![B.B. King, arguably the most famous blues musician of all time, remembers his roots by coming home to Indianola, MS every June and playing a free concert for the home folks. He always follows the concert in the park with a performance at the Club Ebony, a juke house King has played in throughout his career. In his 1996 autobiography, “Blues All Around Me,” King recalls meeting his future wife, Sue Hall, at the club Ebony while playing a gig in 1958. “I found love back down in the Delta,” says King. “I was in Indianola, playing the Club Ebony, with all the musical ghosts of my childhood surrounding me on the bandstand. Couldn’t play that club without thinking of all those nights I spent peeping in on Count Basie or Sonny Boy [Williamson].”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Steber_Good06-768x768.jpg)

“Sometimes they’d just drive that tractor up there and jump off and go on in there,” Alford said, remembering his mother’s Charleston, Miss., joint. “[You’d] see a lot of tractors, mules and stuff. As long as you on the plantation, you could drive the tractor anywhere you want.”

Irene Williams, “Mama ‘Rene” to locals, runs the Do Drop Inn in Shelby, Miss.:

“The juke joints, to me, enable the peoples to go out and ventilate. When you work hard, you’re tense… Not able to pay bills, not able to buy the amount of groceries that you need to buy. Not able to do a lot of things that you want to do.

“And when you go to these places you’re able to ventilate and let off the stress, and you’re able to cope the next week with your problems better.”

In the lawless days of early Delta culture, that blowing off steam would often get violent.

Legendary slide guitarist Robert Nighthawk sang about that darker side of Delta night life in 1964:

I come in home last night just about 4 o’clock,A little moonshine joint in the rear was just beginning to rock.I kind of eased up side to get a bett view,I saw my baby doing the monkey too.Yeah, gonna murder my babyIf she don’t stop cheatin’ and lyin’Well I’d rather be in the penitentiarThan to be worried out of my mind. — “Going Down to Eli’s”

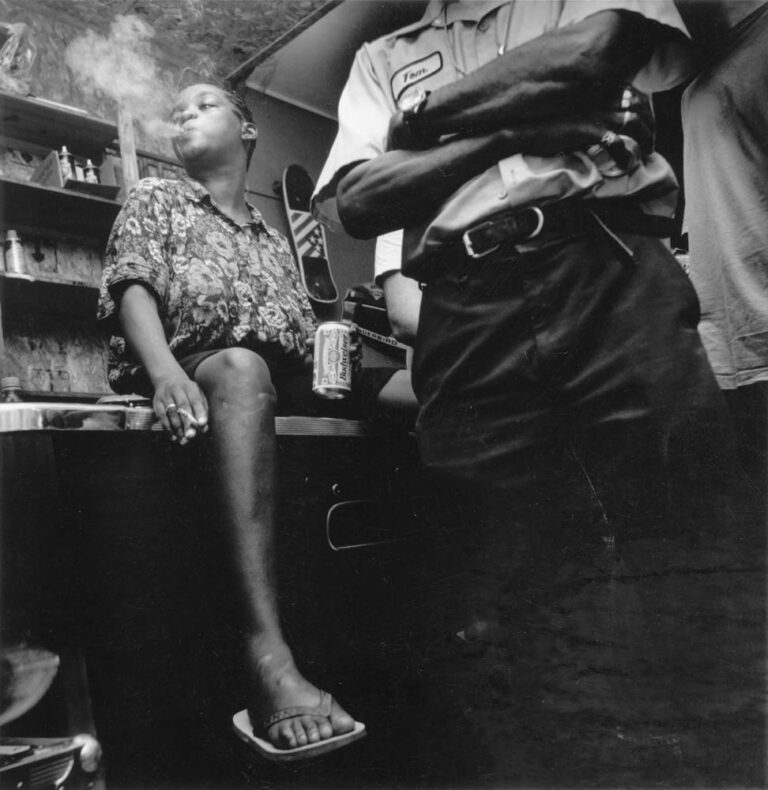

![Everett Wilson (seated) works the door of the Black Castle club in Ruleville, MS on a Sunday afternoon when the club features blues and soul records played by a DJ. A sign posted at the entrance warns customers that no drugs or gang activity is permitted at the Black Castle. Wilson’s father E.V. “Jug” Wilson says that juke joints in the Delta now face a double threat not only from casino competition but also from the influence of drugs. “The money you [used to make] on a Saturday night, them drug dealers [have] it,” says Wilson. “Cause if you just got a little juke up there [on Greasy street], the [drug dealers] tote the biggest roll of money in there.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Steber_Good07-768x769.jpg)

Chester Johnson remembers: “If you stayed there till about 10 o’clock and didn’t nothing happen, you better go on home. ’Cause from about 11 o’clock on there’s gonna be some shootin’ going on. Some guy’s gonna whoop his old lady about dancing with somebody.”

Despite the occasional violence, and the obvious liquor law violations in dry Mississippi, juke operators and their patrons had little to fear from local law enforcement.

“You paid that man to sell that whiskey,” Alford said. “They didn’t say it like that, but that’s all they were doing — paying the sheriff or the chief of police or whoever would let you sell.”

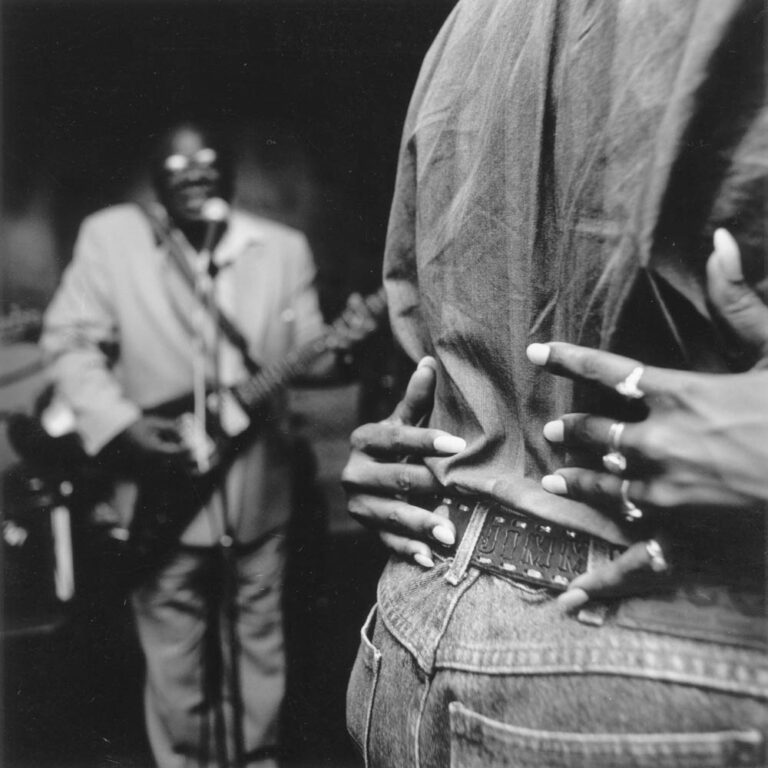

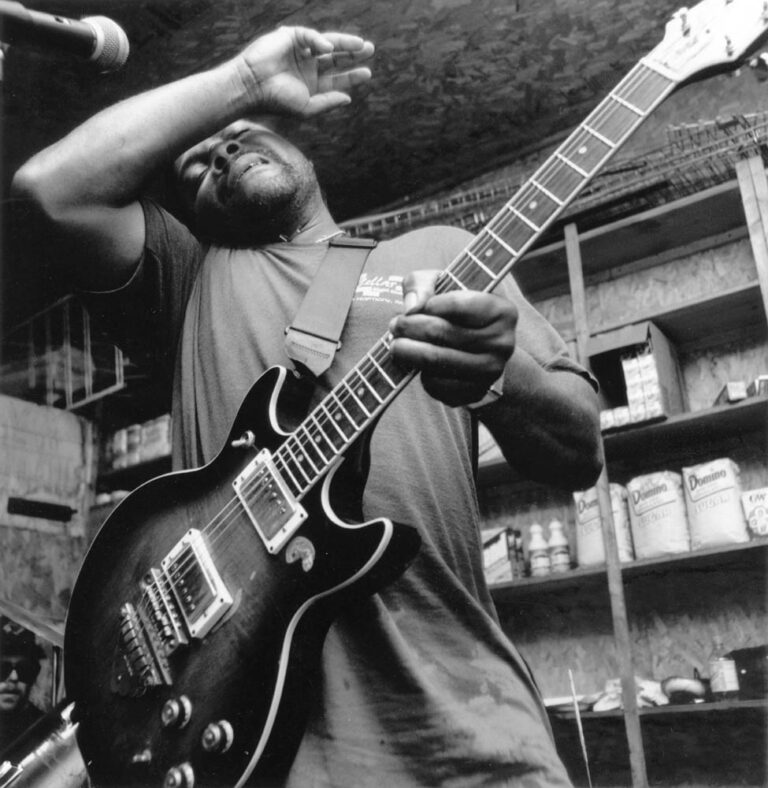

![A blues fan responds to the opening chords of a favorite song during a Sunday night blues jam session of Greenville musicians at Boss Hall’s in nearby Leland, MS. Juke joints that cater to younger crowds on Friday and Saturday with rap and popular music often feature blues for an older crowd on Sundays. James Alford, manager of Smitty’s Red Top Lounge in Clarksdale, MS, explains why Sundays have traditionally been a popular day for jukin’. “[People are] glad to get out of church and unwind a little bit. Most churches hold people too long,” says Alford. “I got nothing against religion, but the attention span in church is not as long as it is in a juke joint.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Steber_Good08-768x759.jpg)

White plantation owners also discouraged police from interfering with the social lives of their tenants.

“If they didn’t call the law, you better not catch the law out there,” Johnson said. “[They’d say] ‘Don’t come on the place if I didn’t send for ‘em.’”

To survive, some juke joints are changing.

Since few Delta club owners make enough from their businesses to live on — even in good times — casino competition has forced many into some creative marketing to lure their customers back, and to reel tourists in.

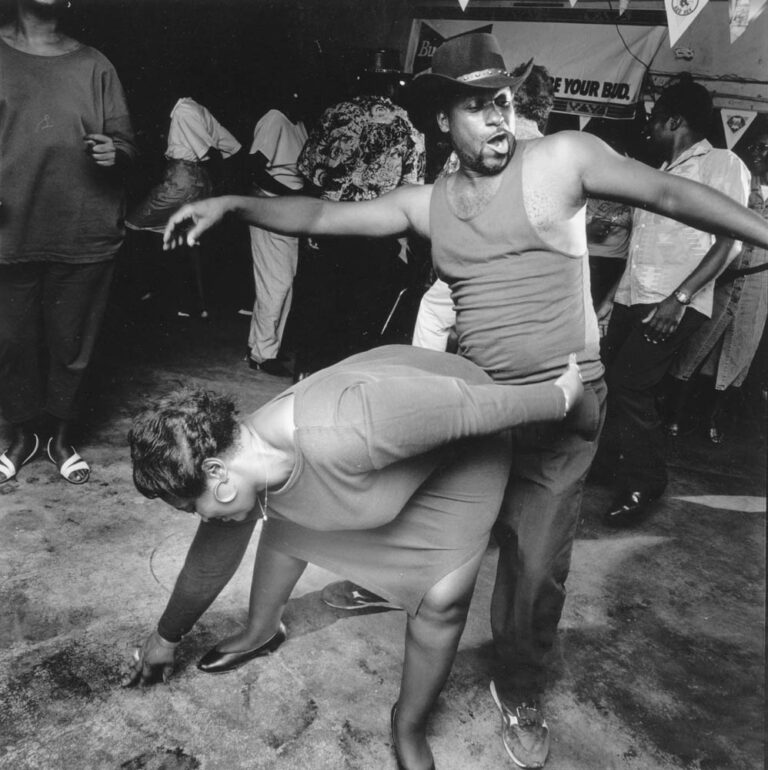

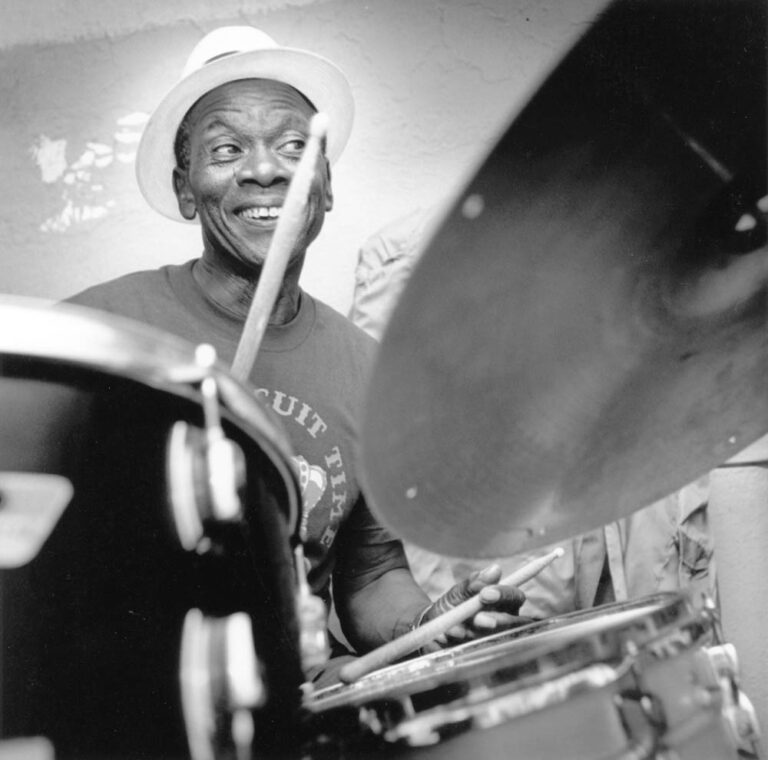

![Keyboardist Leon Jenkins (left), singer Rick Lawson (center) and guitarist King Edward (right) play blues in the early morning hours at the Subway Lounge in Jackson, MS for a typically large and enthusiastic crowd. The popular Subway Lounge is located in the basement of the old Summers Hotel which once housed most of the Jazz and Blues legends that played Jackson earlier in the century. The Subway is open on weekends from 11:00 pm till 5:00 am and often has patrons lined up down the block waiting to get in. Owner Jimmy King says that being located in a metropolitan area in the center of the state far from Riverboat gambling and being an after-hours club insulates him from the casino competition affecting his Delta counterparts. Still, King says if juke joints are to survive, they have to be run for love rather than money. “Only the ones that go into the business not depending on it for a living [will survive],” says King.](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Steber_Good09-768x496.jpg)

Alford says today’s crowds that take in the genuine live blues shows at Smitty’s Red Top Lounge aren’t from around Clarksdale.

“I’ve had a bus load of Belgians, bus load of Scandinavians,’’ he said. “Most of the crowd I get now is tourists and people from out of town wanting to hear the blues.”

Tyrone Jordan who manages the Windy City Blues Club in Shelby, Miss., is one of the many who have added “tease shows” to the lineup, where dancers stripped to the bare essentials, but never got fully nude.

“They really work,’’ Jordan said. “At 2 [a.m.] we were still making eight dollars at the door per person. We’ve never done that in this club before.’’

After a recent show, though, a brawl broke out. It took the Shelby police and nearby Cleveland’s force to restore peace and order. Since then, Shelby has imposed a 1 a.m. curfew, hurting the late-night joints’ dwindling business even further.

E.V. Wright, who runs the Black Castle in Ruleville, Miss., has moved on a step to avoid the scrutiny of small-town officials who frown on the sexy shows.

“I used to have them, but I found out they don’t want you to do that,’’ Wright said. “I let that alone and I told [my son Everett] to start having rap shows. ’Cause a strip show will draw a lot of people, but a rap show will draw more people.”

As recently as 1994, Irene Williams was working to expand her weathered, shotgun shack Do Drop Inn in Shelby. Sunday night live radio broadcasts from the club were packing the house — acts like the Wesley Jefferson band would cook through funky blues and R&B, couples would dance the sensual slow drag and shouts and laughter would bounce off the walls.

That was when Mama ‘Rene was selling enough plates of home-cooked food and tall-boy cans of Budweiser to make ends meet.

Now the food is still good, the beer is still cold. But those crowds are gone — they’re filling the casinos in Robinsonville and Greenville.

She’s finally let the band go, after a year of paying them out of her pocket.

And instead of her dream to retire, run the club on weekends and cook during the week, Williams is looking to sell the club she’s run since 1971, and focus on running her personal care home in nearby Wintonville — assisted living, Delta-style.

“Unless something gives, I won’t be here very long,’’ she said. “I’m going to be in Wintonville, just dreaming about the used-to-be… You see the things that mean so much to you just fade away, you know.

“You heard that song about it used to be? Yeah, I’ll be dreaming about that.”

©2000 Bill Steber

Bill Steber, a photographer for the Nashville Tennessean, is examining the blues throughout the Mississippi Delta.