Shahida Ahmed fled Bangladesh for the United States four years ago, horrified that whoever planted a bomb to blow apart her husband’s body would come next for her.

With no hope of going home again, she is awaiting a decision on her request for political asylum and earning about $300 a week as a live-in housekeeper and babysitter for an uppercrust Manhattan couple.

At 7, Lucia* got her first maid’s job when her father placed her in service to an aunt who sharecropped for the government in their native Mexico. Now working for a childless couple in New York City, Lucia has been cleaning other people’s homes for 32 of her 39 years.

Vilma Cenac left Grenada in 1994, searching for a more lucrative living than the one she eked out as a part-time postal clerk back home. In late June, her Brooklyn bosses — the second family to retain her as a domestic — gave Cenac 30 days notice that they were letting her go.

“Everyone leaves the small place to come here, hoping, really hoping for something better. I housekeep, babysit, everything. Frankly… they need you, you need the job and they tolerate you. Maybe I am wrong, but this is my thinking,” she said. “And I need to get another job in a hurry.”

Following European immigrants, black slaves and their descendants who have dominated the servant ranks across this country, transplants from such regions as South Asia, Central and South America and the Caribbean have been forcing a slow shift in who is hired to do housework. As with domestics who preceded them, these immigrants are a group whose real numbers are difficult to pin down, partly because — as anecdotal evidence suggests — many are undocumented and, just as many legal residents do, are working off-the-books for untaxed cash.

Theirs is an occupation that has never commanded much pay and even less respect. But many of the newest maids — as one indicator of the shift, roughly a fourth of reported domestics were Hispanic in 1997 — say the United States represented a way out of places whose politics could prove deadly or whose economies seemed relentlessly at rock bottom.

“Women who don’t have a lot of alternatives do this disproportionately. They always have,” said Howard University professor Elizabeth Clark-Lewis, author of “Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration.”

“When African-American women couldn’t find office jobs, they did this work. They still do this work. When immigrant women don’t have skills or the right papers, when they have language barriers, they do the job that is available to them,” Clark-Lewis continued. “We are talking about an invisible empire of workers.”

Federal officials have a more precise tally of, say, those who clean hotels and offices. But the number of individuals working in private homes is more elusive. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that 1 million people do not report their household workers, whether illegal or legal residents, presumably to avoid paying required taxes and workers compensation insurance.

The official count of reported household domestics, a fraction of whom are men, has fluctuated from 980,000 in 1983; 782,000 in 1990; 821,000 in 1995, and 795,000 in 1997. According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the portion of reported black domestics dropped from almost 30 percent in 1983 to about 16 percent in 1997, while the number of Hispanics jumped threefold to roughly 27 percent during the same period. Whites comprise the bulk of the remaining reported domestics. Federal statisticians say the number of Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American and other reported household help was too small to be reliable.

Professor Clark-Lewis contends the incomplete data paint an unclear profile and that, especially outside such major cities as New York, Boston and Los Angeles, black domestics still account for a majority of housekeepers.

Indeed, some of the newest maids are here legally, even if on temporary permits like Ahmed’s. An untallied stream of others, such as Lucia, stole over borders. Advocates say they probably are the most vulnerable of domestics.

Among other constraints, undocumented workers are unlikely to risk deportation by pressing in court their charges of unpaid wages and other on-the-job abuses.Whatever their citizenship status, domestics can find themselves answering to the best and worst employers.

“There often are employers who pay good wages and have workers work reasonable hours. But other people use the arrangement as an excuse not to follow the law, to continue the master-servant tradition,” said attorney Jennifer Gordon, founder of the Workplace Project, a Long Island, New York non-profit agency whose Hispanic clients include domestics.

Federal law classifies as a household worker anyone earning at least $1,000 a year cleaning homes, caring for children — about a third of reported domestics last year were babysitters — keeping up the grounds and so on. It does not entitle domestics to rest periods, premium pay on holidays and weekends, advance notice of termination or severance pay. It does grant them minimum wage and, except for those who live in, overtime pay that is one and a half times their normal salary. Meals and accommodations provided by employers can be considered as a part of one’s wages.

Ahmed sends the bulk of her earnings to the six children and widower father she left behind in her hard scrabble homeland. Her husband was killed there, she suspects, by order of a Bangladesh political party that had employed them both.

At $1,250 a month, her salary is substantially higher than that of every other domestic in Workers Awaz (the Hindi, Urdu and Bengali word for “voice”), a Manhattan non-profit organization for South Asian women.

“There are some members for whom even eating is a big deal; the employer monitors what they eat, how much they eat. Some don’t get days off, “ Ahmed, president of Awaz’ board of directors, said in Bengali through translator Anannya Bhattacharjee, the group’s founder. “There are health issues. Workers who use such strong chemicals their hands are always red and swollen, one worker whose arm hurts terribly from the constant motion. There is no fixing the problem — except to change the work.”

Or, as she did, negotiate. Because she demanded it, the husband and wife physicians who employ Ahmed raised her salary from $900 a month to its current level and reduced her work week from seven to five days. She takes half of Saturday and all day Sunday off and a portion of Wednesday for English lessons.

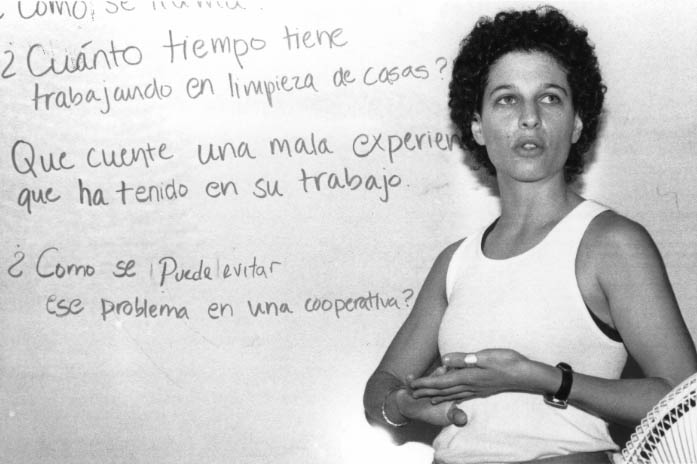

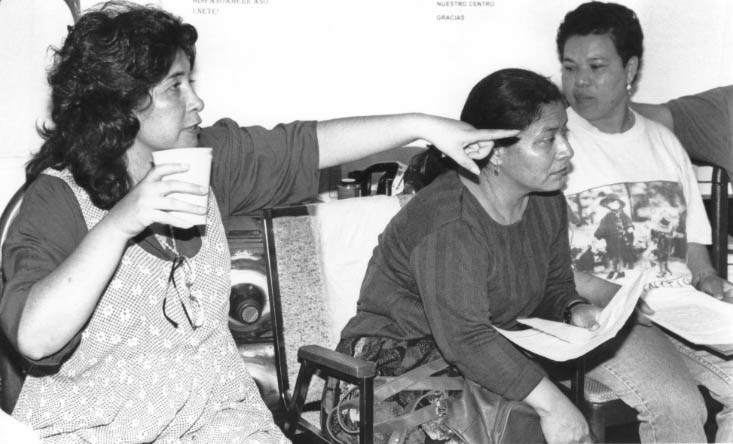

During June’s first “general assembly” of a fledgling domestic workers cooperative of Long Island’s Workplace Project, organizers hammered home the notion of demanding from employers what workers believe is due them, including just wages. The nine twentysomething-to-sixtysomething domestics at that first meeting — 14 showed up at the second meeting, a week later — generally said they took in anywhere from $25 to $65 for a day’s work.

This as the hourly wage for all occupations in the New York City metropolitan area averaged $19.23 and that of service workers, $12.17 in February 1997, the latest date for which the figure is available.

“How do domestics survive financially? They live by praying,” said Juan Carlos Molina, a Salvadoran helping to launch the cooperative that is modeled after similar efforts in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Housekeeper Luz Torres, president of the project’s board, has been cleaning homes for most of her 17 years in this country.

“The first family I worked for, they were good to me. But I made them understand that I was a person…and that they had to respect me,” she said.

She has a dozen or so clients, refuses to work for those who do not treat her as she wants or who won’t buy the Shaklee housecleaning products she sells to help make ends meet.

Susan Caspi, a family lawyer, is among Torres’ favorite employers and the niece of Torres’ first homeowner boss. Growing up in posh Dix Hills, Long Island, her family always had a live-in housekeeper. One she remembers as “Marta” sticks in her memory.

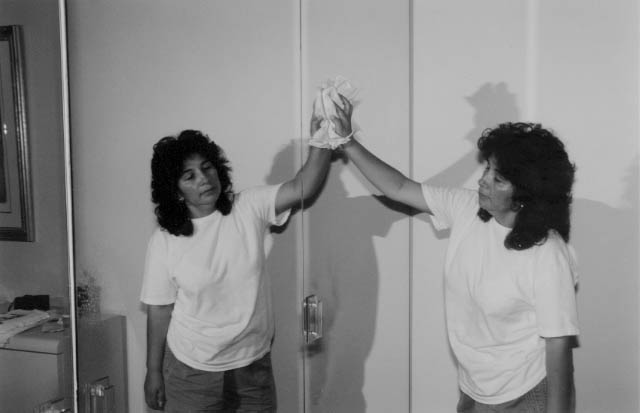

“To us, she was not a housekeeper but family. They ate dinner at our table. I played with her son like he was my younger brother. I taught him English,” Caspi said on a day when Torres was whipping through Caspi’s condo, pouring Shaklee detergent into the wash, retrieving bundles from the dryer, rubbing fingerprints from mirrored closet doors.

“I don’t do this job because I love it. But it gives me the freedom to do organizing. I have good customers and they give me space,” said Torres who organized factory workers in her native Colombia and is rallying domestic workers here.

For every maid in an acceptable situation with a fair employer, there exist others who stand on more precarious ground.

Before he left the Latino Workers Association on the Lower East Side for a labor lawyer’s job with a Manhattan firm in May, attorney Peter Rukin filed a complaint with the New York State Department of Labor alleging that Guatemalan Blanca Ramirez worked a decade as a live-in housekeeper, was given meals and personal quarters but no pay by her employer.

“Sometimes the most egregious cases are the most difficult ones to win. If you claim you worked for free for 10 years, it was such a long period of time that the employer can say, ‘Oh, no. She was just living here,’” Rukin said. “People like Blanca are a very disempowered group.’’

Washington, D.C. attorney Ed Leavy has represented several foreign-born domestics in cases against employers working at such international organizations as the United Nations and World Bank.

Most recently, he has been suing for six years’ worth of back wages for an Ethiopian woman, Ayelech Mamo. She says Elizabeth Iyob and Tewolde Iyob, Ethiopian natives brought her to the United States in 1990 with the promise of $400 month to live in and clean the Iyob’s Maryland home and care for the couple’s children.

She never received a penny, Leavy said.

“Mamo is a peasant. She couldn’t even read her own passport,” he said. “As far as I am concerned, these kind of people are involved in a modern-day slave trade.”

Iyob referred to Mamo’s place in the household as an “arrangement” and said she was not the family’s employee.

Some say little has changed for housekeepers in this country, despite the clamor over millionaire Zoe Baird, the lawyer President Clinton nominated to the Supreme Court in 1994. He withdrew the nomination after Baird came under attack for hiring a Peruvian couple off-the-books to care for her child and Connecticut home.

Indeed, even the number of employers paying taxes on household hires has fallen dramatically from about 500,000 in 1994 to 300,000 in 1995 and 314,000 in 1996.

In a 1997 study, “Out of the Shadows,” the National Organization for Women Legal Defense and Education Fund found, among other gaps, that more than half the states did not extend civil rights laws to domestics and either restricted or altogether barred domestics from workers compensation coverage. Several states have no laws shielding domestic workers from sexual harassment by employers.

In November 1997, the Center of Immigrant Rights in Manhattan published “Home Improvement: A Guide to Building a Stable Relationship With Your Household Worker,” to explain New York’s laws to employers.

It has relied on churches, synagogues and other word-of-mouth means to publicize the $10 booklet. “Unfortunately, we’ve had minimal success getting it circulating,” said Melanie Ryan, a Rutgers University law student and member of the center’s staff.

Attorneys Gordon and Rukin say state labor officials charged with overseeing workplace issues are swamped with cases and, arguably, reluctant to hear disputes involving what goes on in someone’s home.

“Government is more likely to treat it as a family than a private concern,” Gordon said.

As much as domestics want the worst employers to meet their legal obligations, some housekeepers also say they want an end to the kind of slights that gnaw at their human core.

Grenadan Jennitha Sampson has only done housework since moving to New York 10 years ago with her Trinidadian husband and three children.

Her first job was with a New Jersey couple that only ate kosher food and refused to let her bring her own food into their home.

“I leave when I couldn’t take being hungry anymore,” she said. “The world needs to know about this.”

Alba Gutierrez holds up bosses who have treated her with respect, including the doctor who “gave me medicine when I was sick and let me bring my son to her house.”

But her most bitter memory is of the retiree who handed Gutierrez leftover chicken that, though sealed in a brown bag, had been retrieved from the homeowner’s garbage chute.

“She said she knew I was very poor, and that I might need it” Gutierrez said in the English she has been refining during 15 years of life here. “They believe that because we clean houses, we do not have dreams.”

It is, however, anyone’s guess how close many domestics will come to achieving them.

“Some women will move in and out of this,” attorney Gordon said. “But my sense is that, for many women who come here, this will be their life’s work. Even if they have the desire, it seems they don’t have the option to do anything else.”

©1998 Katti Gray

Katti Gray, a reporter for Newsday, is researching maids in America during her Patterson year.