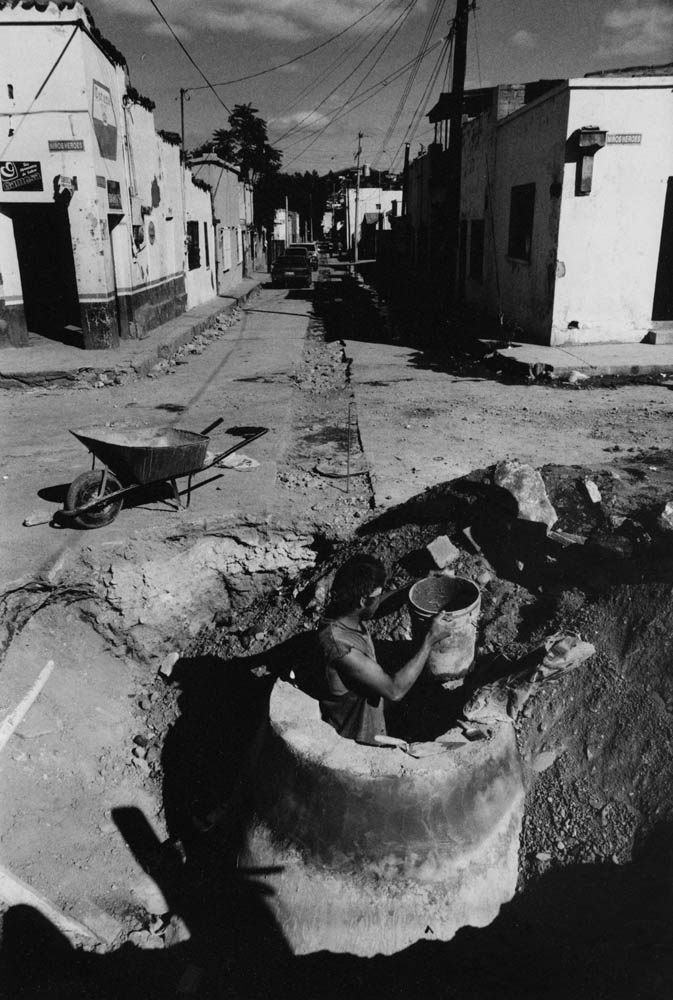

In the hillside shantytowns of Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, people get drinking water from trucks and store it in barrels salvaged from the dump or nearby factories. They have no choice. The city’s crumbling, 50-year-old water distribution system doesn’t extend to where they live. Even most of the homes in town that are connected to the system only get water a few hours each day. Leaking pipes, illegal connections, and steep hills reduce water flow and pressure to such an extent that what’s left has to be rationed.

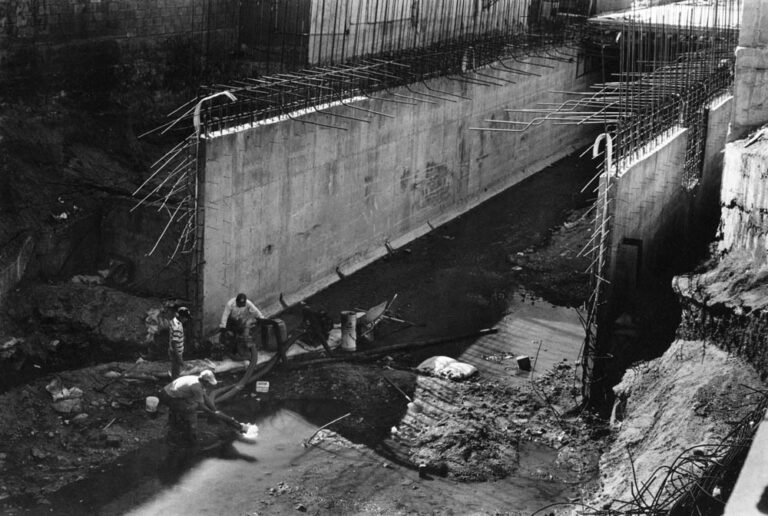

Nogales, Sonora’s wastewater system is in equally bad shape. Most shantytown residents aren’t connected to it at all. They use makeshift latrines and outhouses, the contents of which seep into the soil and run into the washes. Like the water system, the sewer lines are old and leaky and break frequently. When it rains, garbage and debris-laden water courses into the sewers, clogging pipes and overloading the city’s binational treatment plant that lies nine miles downstream on the U.S. side of the border.

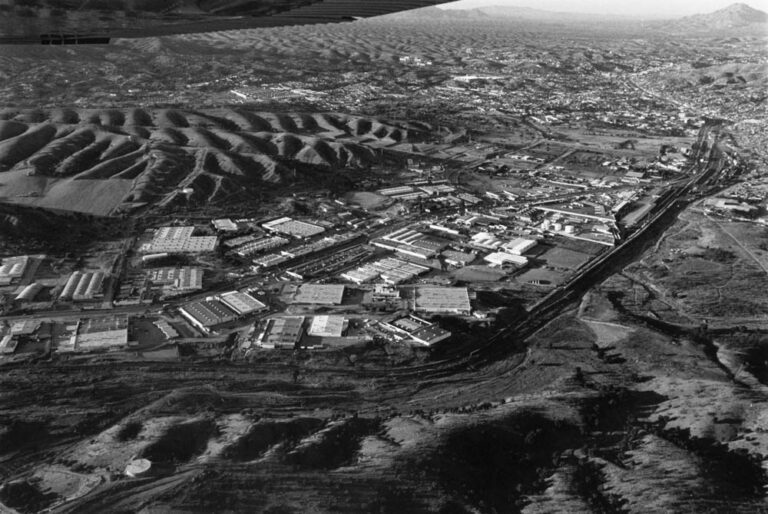

Nogales, Sonora, is only one of many cities on the U.S.-Mexico border with water and wastewater problems. The tens of thousands of people who have moved to the region in recent decades to work in maquiladoras, or foreign-owned factories, have totally overwhelmed the inadequate infrastructure. An estimated 40 percent of residents on the Mexican side lack water, sewers, or both. Ciudad Juarez, one of the largest cities on the border, has no treatment plant at all. It dumps 22 million gallons of raw sewage into the Rio Grande every day. From a public health standpoint, the lack of water and wastewater systems is the most crucial environmental challenge facing the border.

The U.S. and Mexican governments recognized the challenge four years ago when, to secure passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), they agreed to provide grants, loans and technical assistance to help build infrastructure. Since that time, work has begun in several cities, including Nogales, Sonora. Although it is too early to say whether these NAFTA-related projects will be able to transform living conditions, they have brought new money and attention to the border’s problems, and some, especially the one in Nogales, have generated considerable controversy. The Nogales project is an example of both the promise and the pitfalls of what NAFTA supporters herald as “a new era of environmental cooperation on the border.”

Although most of the planned repairs and expansion of the Nogales water and wastewater systems are taking place on the Mexican side of the line, the U.S. side has an important stake in the process. For one thing, Mexico lacks the money and expertise to do the job on its own. For another, the topography of the region makes joint planning essential.

Ambos (Both) Nogales are nestled together in a narrow valley that is susceptible to droughts and floods. Nogales, Arizona, population 20,000, lies downhill and downstream from Nogales, Sonora, a city with at least ten times as many people. If the two sides fail to work together, their shared underground aquifer could be sucked dry or contaminated, and their shared treatment plant could be damaged or overwhelmed. “The futures of both communities are totally dependent on one another,” said Placido Dos Santos, border environmental manager for the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality.

ADEQ is one of a number of government agencies on both sides of the line involved in planning improvements to the wastewater system in Ambos Nogales. Placido Dos Santos and others describe the effort as a model of binational cooperation. In contrast, plans to improve the Nogales, Sonora, water system have been controversial from the start. Critics say that work is proceeding without enough regard to environmental or financial consequences.

The aquaferico, as the water project is called, is an ambitious, $39 million plan to build new wells, pipes, and storage tanks, and to repair and expand the current distribution system. Using a $10 million grant from the Mexican government, authorities in Nogales, Sonora, have begun work on the first phase of the plan, which calls for pumping more water from an aquifer that lies 15 kilometers south of the city. This aquifer (which is not connected to the binational aquifer shared by Ambos Nogales), now supplies about one-third of Nogales, Sonora’s water. But environmentalists say it is too shallow to sustain much more pumping.

“There’s already been a severe decline in the wildlife in that area and the wells in the ejidos [communal farms] have been drying up,” said Teresa Leal, an activist in Nogales, Sonora. “We are putting all our eggs into something that doesn’t exist.”

Much of the criticism of the aquaferico has been directed at two new, binational agencies that are backing the project, the Border Environment Cooperation Commission (BECC) and the North American Development Bank (NAD-Bank). Both were set up in the wake of NAFTA to help build infrastructure on the border. Leal says the BECC ignored public concerns and failed to require proper impact studies before approving the aquaferico. Critics also question how impoverished local residents will be able to repay the initial $8 to $10 million that the NAD-Bank is expected to loan the project. Leal said that most people in Nogales already are having trouble paying their water bills, which have gone up sharply in recent years. She and others believe that the maquiladoras should be required to bear part of the cost.

Nogales, Sonora, water officials downplay the critics’ concerns. They say the new water system will be much more efficient than the current one, which, according to some estimates, is so leaky that nearly half the water pumped never reaches its destination. “Once we recapture that water, we won’t have to pump so much,” said Antonio Guzman, an official with the Sonoran state agency that oversees the Nogales water department.

Aquaferico supporters also point out that many people in Nogales now don’t pay for water because the service is so bad. They say that, after service and collection methods improve, the cost will be shared by more customers and rates won’t have to go up as much as projected. In addition, shantytown residents who now get water from trucks already pay up to 400 percent more than people connected to the system. If service is extended to where they live, their costs actually could go down. As for the maquiladoras, Guzman said most of the companies have private wells, and so cannot be forced to pay for a water system they don’t use.

Gonzalo Bravo, coordinator of public participation for the BECC, said he believes the aquaferico project is sound, but his agency did learn from the controversy surrounding its approval. “We learned that it’s important to have a local citizens’ committee in place before the project is considered,” he said. Since the aquaferico was approved in January, 1996, Bravo said a number of other projects, including a wastewater treatment plant for Ciudad Juarez, have been approved with full local participation. He added that, when the Nogales wastewater project comes to the BECC for approval next year, a steering committee of people from Ambos Nogales will be in place before any decision is made.

Work on the Nogales wastewater project already is proceeding differently from that on the aquaferico. The U.S. side has been extensively involved because, unlike the water system, the wastewater system is binational. The U.S. has provided $2 million in grant money and technical assistance for a “quick-fix” program to keep storm water from running into the sewer lines in Nogales, Sonora. It also is paying for an unprecedented planning process over the future of the wastewater system.

Currently, all the Nogales, Sonora, wastewater that flows into the sewer is treated and discharged on the U.S. side. The U.S. side wants to keep this effluent in southern Arizona, where it feeds a thriving riparian area. But the Mexican side wants at least some of it back to help recharge the binational aquifer on which both communities primarily depend. The planning committee is looking at dozens of options, including pumping some of the effluent back to the Mexican side of the aquifer, and/or building another treatment plant in Nogales, Sonora. So far, negotiations are going well, but hard decisions have yet to be made.

“This is going to be a test of how cooperative everybody can be,” said Richard Mestan, an environmental engineer with the International Boundary and Water Commission, a federal agency involved in the wastewater planning process.

Even if agreement can be reached, the question remains whether there will be money available to build the new facilities, let alone operate and maintain them over many years. The same doubts that have arisen over repayment of NAD-Bank loans for the water system are likely to arise over loans for the wastewater system as well.

All along the border, people are concerned not only about the cost of NAD-Bank loans, but from where else the billions needed to build water and wastewater systems is going to come. “Right now, both the U.S. and Mexican governments are directing a lot of grant money and other resources toward the border,” said Placido Dos Santos of ADEQ. “What happens when that ends?”

Dos Santos believes that, sooner or later, border communities will have to turn to industry to bear some of the cost of building and maintaining infrastructure. “The maquiladoras are driving population growth on the border,” he said, “and they share some responsibility for paying for it.”

©1998 Miriam Davidson

Miriam Davidson, a correspondent for the Arizona Republic, is examining the town of Ambos Nogales, along the U.S.-Mexican border.