Photographs by Jeffery Scott

From his office window, Tom Higgins looks across the city of Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, and sees rows of new tin roofs shining on a hilltop. “I’m so pleased,” he says, “that in all the crap and corruption of this world, the little guys got something good.”

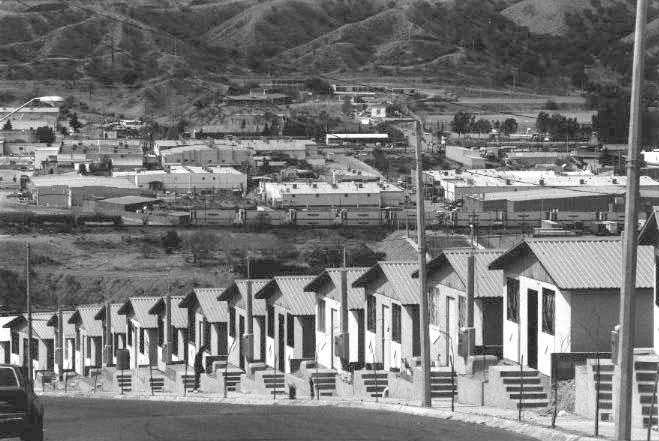

Higgins has reason to be pleased. As manager of one of the 82 maquiladoras, or foreign-owned assembly plants, in Nogales, he helped pioneer a unique collaboration between his industry and the Mexican government to provide housing for low-income maquiladora workers. The first 500 single-family, worker-owned homes were built last year, and another 250 will be finished by this summer. The program has been so successful in Nogales that it recently was expanded to other border cities.

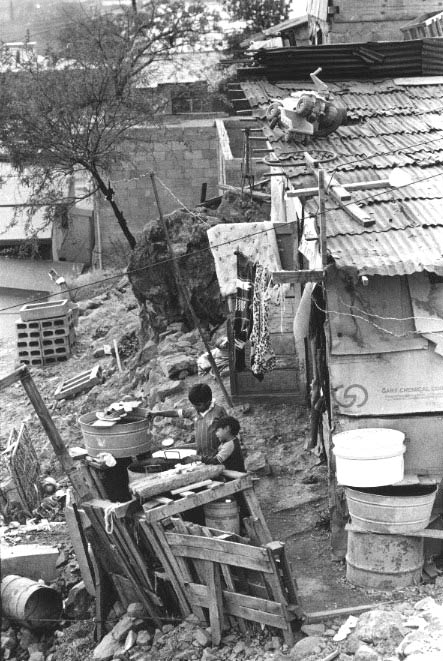

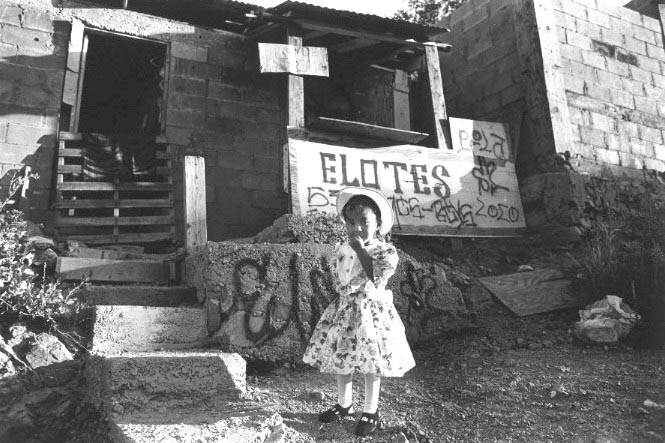

The housing program represents an unprecedented effort to confront one of the main criticisms of maquiladoras: the lack of housing and infrastructure for workers who make less than $10 a day. Many, if not most, of the more than 800,000 maquiladora workers in Mexico live in crowded squatters’ camps surrounding the factories. Their shacks are cobbled together from wood pallets, scrap metal, cardboard boxes, and plastic sheets. Few have indoor plumbing. Some, particularly new arrivals to the border, don’t have water or electricity.

“We all feel shame about the deplorable living conditions that still exist for newcomers,” says Marco Antonio Valenzuela, head of the Mexico City-based National Council of the Maquiladora Industry. “Hopefully, this program will have a long-term effect toward eliminating the housing shortage on the border.”

Tom Higgins, who calls himself “a gringo with a Mexican soul,” has worked in the Nogales maquiladora industry for 12 years. For at least half that time, Higgins, his former boss, and a handful of others also have worked to get the housing project built. It hasn’t been easy.

Higgins’ former boss proposed the idea in 1990, after reading an article about the Nogales maquiladora industry in the New York Times Sunday magazine. It depicted a family living in a shack made out of cardboard boxes. The boxes had the name of his company’s maquiladora printed on them. “I had pangs of guilt,” says Douglas Chapman, the retired chairman of ACCO World Corporation, a Chicago-based office-supply manufacturer. “I felt that, if we’re profiting and benefiting down there, we had an obligation to try to do something about this.”

Chapman and another senior ACCO executive then put up several hundred thousand dollars of their own money to start the Esperanza (Hope) Foundation. The idea was to use this money, as well as contributions from the Nogales maquiladora industry, to help workers make down payments on government-financed homes. “We wanted them to be nice houses, with bedrooms, bathroom, water, sewer, electricity, paved streets, sidewalks, and street lights,” Chapman says. The foundation also required that the houses be fairly distributed among all qualified maquiladora workers in Nogales.

The Nogales maquiladora industry had some objections to the plan. Maquiladoras already pay a 5 percent housing tax to the Mexican government, money that, in the past, has not been used to benefit their workers. Managers point out that their companies contribute millions to the Mexican economy through salaries, taxes, and local suppliers. They also don’t like the fact that the foundation was set up to benefit all maquiladora workers, not just workers for contributing companies.

Nevertheless, with the Esperanza Foundation leading the way, most of the maquiladoras in Nogales have agreed to help qualified workers make a down payment on a home. Some are doing it through the Esperanza Foundation. Others are giving all or most of the money directly to their employees.

“It doesn’t matter how they do it, as long as they do it,” Chapman says. Getting the support of the maquiladoras wasn’t the only hurdle the foundation had to overcome. Problems with an unscrupulous developer and the economic and political turmoil of the 1994 peso devaluation forced the project to be delayed and scaled back several times. Things finally came together in late 1995, when INFONAVIT, the Mexican government’s low-income housing authority, agreed to finance the construction. INFONAVIT also agreed to make the houses affordable by easing its requirements to qualify for a home loan. Such loans had previously been out of reach for most maquiladora workers.

Today, the $10 million San Carlos project, looking much like Chapman and Higgins envisioned it, is going up on a hill above a new industrial park on the east side of Nogales. The first 500 of the 511-square foot, two-bedroom homes were presented to their owners in a ceremony last fall. At least one worker at each of the 41 companies that belong to the Nogales Maquiladora Association – employers of some 90 percent of the 25,000 maquiladora workers in town – received a house.

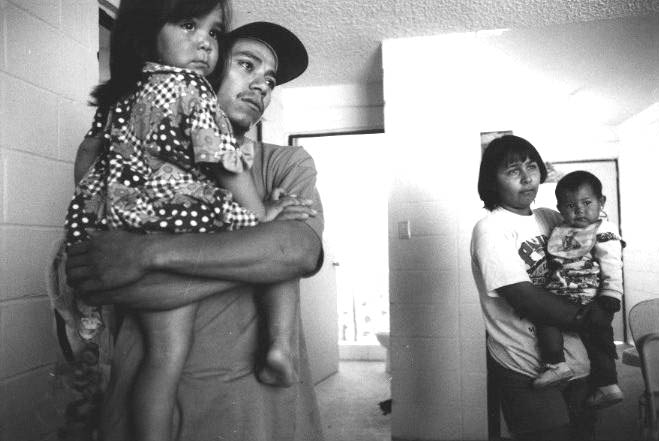

Andres Espericueta says he considers himself lucky to have gotten a house in San Carlos. “This is pretty nice, better than where we were before,” says Espericueta, 25, as he holds his 2-year-old daughter, Andrea, in his arms. He and his wife Karla, 26, also have an 8-month-old girl named Zulay. They used to live with Karla’s relatives in another part of Nogales, in a house not much bigger than this one. The family has been living in their new home since January, and, although the living room is bare, Karla describes the house as “very comfortable.”

Espericueta works for Tom Higgins at S.L. Waber de Mexico, a maquiladora that makes surge suppressors and voltage regulators. He has been there four years and makes about 60 pesos (currently, $8) a day. He was the only one of Waber’s 425 employees to get a new house.

“Your income has to be in a certain range, not too low and not too high, to qualify,” he says. The Esperanza Foundation paid his $2,100 down payment, and he owes INFONAVIT a mortgage of about $9,500, plus 6 percent annual interest. He will pay it back through payroll deductions of one-quarter of his weekly salary for the next 20 to 30 years. “I think it’s fair,” he says, adding that he has friends at work who also could qualify, if more houses become available.

Like the Espericuetas, most of the families living in San Carlos are in their 20s, with children, and have worked in the maquiladoras for several years. They make between two and three times the minimum wage, which on the border is currently about 26 pesos, or $3.50, a day.

The fact that only long-term employees received houses illustrates how the program benefits maquiladoras as well. The industry has been plagued by high turnover, which many attribute to the lack of decent housing on the border. “One of the intentions of the program is to stabilize the labor force,” says Marco Antonio Valenzuela of the National Council of the Maquiladora Industry.

Espericueta says he didn’t have to promise to stay at Waber in order to get the house, but he expects he will. He says Tom Higgins is a good guy to work for, better than most.

Now that Higgins and others proved the program could work in Nogales, INFONAVIT is taking it border-wide. Last summer, officials announced plans to offer similar loans and credits to low-income maquiladora workers in the cities of Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa and Matamoros. They expect to build 18,000 homes over the next three years.

General Motors, the largest foreign employer in Mexico, has agreed to subsidize at least half the cost of a down payment for 6,000 of its workers. Other companies are considering doing the same. Marco Antonio Valenzuela says he also is developing a plan to expand participation among his organization, which represents hundreds of maquiladoras in 22 cities nationwide. He believes that most companies will contribute, as long as they only are asked to support their own workers.

Tom Higgins, meanwhile, is trying to figure out a way to systematize contributions to the Esperanza Foundation so that more homes can be built in Nogales. He figures that if all 41 members of the maquiladora association put in 5 cents an hour per employee, more than $2 million a year could be raised. So far, only ACCO’s maquiladora has been making regular contributions, although a couple of other companies recently pledged to spend up to $200,000 a year to help their workers with down payments. “In spite of what we’re doing, the job at hand is larger than we know, and in the future we should be doing more,” Higgins says.

From his office window, Higgins can see not only the rooftops of San Carlos, but some of the shantytowns where most maquiladora workers still live. The view puts his efforts in perspective. “We haven’t solved the problems of the two to three hundred thousand who live in this city,” Higgins says. “But those houses weren’t on that hill a year ago.”

©1997 Miriam Davidson

Miriam Davidson, a correspondent for the Arizona Republic, is examining the border town of Ambos Nogales.