Teenage murderer James Morgan didn’t go the electric chair. But is his life worth living?

In 1987, when I first interviewed James Morgan, he was on death row in Florida, sentenced to die in the electric chair for murdering a widow in a small town north of Palm Beach. He killed her when he was 16 years old.

Local newspaper reporters struggled to find words for the crime: Heinous, grisly, and senseless didn’t do it justice. Nothing could describe what Morgan did to 66-year-old Gertrude Trbovich, a widow who lived on a narrow drive with homes on manicured lawns, flanked by hibiscus and palm trees.

Morgan was evil, wicked, and vile, the prosecutor said at trial. Yes, he was young. But he was incapable of change and would never find a moral compass. People like him were a danger to society whether they were 40 years old, 60, or beyond. As of 2016, Morgan’s “expected release date” is set for 2094, when he’d be 134 years old.

“Have you watched how he doesn’t move?” Morgan’s public defender told jurors at one of his trials. Morgan had four trials, each one of them ending in the death penalty and each overturned on appeal.

“Look at him,” the public defender said, trying to make jurors see that Morgan was mentally ill. “He sits in the same position for hours and hours!”

What jurors saw was a blank-faced young man who didn’t look sorry enough. At one trial he wore a blue and yellow checked sports coat and light blue pants, the local newspaper noted. He was described as emotionless.

The jurors’ compassion evaporated, as it would for anyone, when they saw the full-color photos of Trbovich beaten and slashed to death, and a knife encrusted with her blood. In Morgan’s case, the prosecutor placed the knife on the railing of the jury box. It took jurors only about an hour of deliberating before they recommended the death penalty.

By the time I met Morgan, I’d also looked at crime scene photos. But I was also trying to look at another part of the picture. I was traveling to death rows around the country for a magazine article about the dozens of juvenile offenders who’d been condemned to die, a number that would eventually grow to 226. Some of the teens were as young as 15 at the time of their crime. In all, 22 would be executed.

There was a central theme in their cases: Prosecutors argued that the teens could never change.

How anyone could predict the future that way was a mystery to the American Psychological Association, the American Bar Association, human rights groups, defense attorneys, social workers, pediatricians, and parents, who knew that teenagers turned into a different person often enough to cause whiplash.

For years, on and off, I thought about the death row teens and wondered how they’d grown up. Morgan was among the most damaged of all of them. If he could transform himself even in a small way, it could prove prosecutors wrong, I imagined. But I knew I couldn’t gauge his progress unless I could meet him decades in the future.

This past year, I got the chance.

THE MURDER

On June 6, 1977, Gertrude Trbovich went shopping with one of her friends before returning home to Stuart, on the Treasure Coast in southeast Florida. The beloved mother, mother-in-law, and grandmother lived in a pretty neighborhood on a street above the St. Lucie River.

Morgan lived on the poorer side of town. His father had a lawn maintenance business and asked his three kids to help out with the mowing when they weren’t in school. By ninth grade Morgan was free to help out every day.

Morgan had struggled in school since kindergarten, about the time an older cousin introduced him to sniffing gasoline, court documents said. The habit made Morgan hallucinate and hear things that nobody said. But Morgan didn’t mind it, aside from the fact that he got a whipping from his mom if she caught him.

In grade school one of Morgan’s uncles began to sexually abuse him; two cousins molested Morgan as well, legal documents said. Morgan’s parents argued over his father’s heavy drinking, which his mother didn’t approve of, the documents added. Sniffing gasoline, at least, helped Morgan forget things.

It also caused brain damage. Morgan dropped out of school after eighth grade. He still couldn’t read or write. By age 15 and 16, he was getting drunk more and more often. His father put him to work.

On the day in question, Morgan was mowing the lawn for Trbovich. He had a hangover from sniffing gas and getting drunk the night before.

When a cousin dropped him off at Trbovich’s house that afternoon he was barefoot and wearing a denim jacket, despite the pressing heat. That day he’d sniffed gasoline and had some beer, and now he felt even sicker. He wanted to call his father and get a ride home.

Trbovich was in the cool of her dining room when she heard the knock on the door. She opened it and saw a pale, bedraggled 16-year-old with dirty blond hair to his shoulders, tall for his age, and shoe-less. Morgan asked to use the telephone, and she let him inside.

But when Morgan dialed his father, he got no answer. He was starting to feel angry. He asked to use the bathroom. Trbovich gave him permission.

As he walked past her—she sat quietly at her desk, writing a letter—he began to think she’d smelled the beer on his breath. He thought he heard her mumble something about reporting it to his mother.

Trbovich was going to tell his mother he was drinking, he convinced himself. His mother hated drinking. He was going to be in big trouble.

When Morgan left the bathroom he saw Trbovich, still writing a letter. It was to his mother, he thought.

He took a crescent wrench from his pocket and bludgeoned her on the head. She looked at him, terrified. He saw “a look of disgust”—the same look he’d seen on his mother’s face when she was angry about his father’s drinking.

Enraged, Morgan beat Trbovich with the wrench and smashed her with a glass vase. He fractured her skull and pounded one of her hands so hard that her wedding ring flattened into an oval.

He picked up a serrated knife and stabbed her 67 times, court records said. He bit her on the breast, sexually assaulted her, made a brief attempt to clean up some of the blood, and fled.

Police found Morgan’s bloody bare footprint on a piece of stationery that fell to the floor. Trbovich had written the time in the corner: 3:15 p.m. The letter stopped in mid-sentence.

Morgan deserved life imprisonment, not death, his public defender argued at the trial six months later. The boy couldn’t remember the stabbing; he was a brain-damaged 16-year-old with the emotional maturity of a grade-schooler; he was in a psychotic frenzy when he attacked the elderly woman; and he was legally insane at the time, the defense attorney said.

The prosecutor countered that Morgan was utterly sane and that the murder was premeditated. The teenager was “a pretty cool cat” and “a controlled, insensitive” killer, a psychiatrist testified. Jurors agreed.

By New Year’s Eve, 1977, Morgan was in an airplane for the first time in his life, handcuffed and shackled in a single-engine plane en route to prison in the piney woods of north Florida. He’d be on Florida State Prison’s death row for more than 16 years.

THE MEETING

I heard Morgan before I saw him. He rounded a corner wearing handcuffs connected to a belly chain around his waist, and leg shackles that kept him at a shuffle, the chain clinking between his ankles.

Morgan was 6-foot-2 and bone-thin, with a pale, narrow face. A guard brought him to the narrow, concrete and plexiglass interview room and he arranged himself across the table from me, clinking even more loudly. He said hello, almost inaudibly. He looked disoriented.

“I didn’t know the interview was today,” he apologized.

Morgan was 27 years old. He’d lived for a decade in a windowless 6-by-9-foot death row cell, 23 hours day, at Florida State Prison, home of the notoriously malfunctioning electric chair Old Sparky, which in the future would set a man’s head on fire.

His cell was a stifling, three-sided concrete vault, big enough to take a few strides up and back. He couldn’t see other inmates without holding a mirror through the front bars. But he could hear them. The din was relentless: shouts, screams, mouthing off, and the metal-on-metal overdub of banging steel doors, slamming gates, and jangling shackles.

The sounds traveled everywhere, including to the narrow room in the main part of the prison where I’d waited for Morgan to appear. “I’m a little nervous,” he told me.

A correctional officer came for him that morning, handcuffed him, strip-searched him, shackled him, and escorted him to the main part of the prison where interview rooms are located, and also where inmates go if there’s bad news. “The officer wouldn’t say nothin’ about where we was going.”

Morgan said he was sure they were headed to the “colonel’s office,” where inmates are taken when the governor signs their death warrant. Then a guard locked him in a nearby holding cell for hours. The whole time, Morgan was convinced he was going to be executed soon.

He had a receding chin and long, delicate fingers, the only thing about him that seemed willing to move. He mumbled. His right hand gravitated to the side of his face and wanted to stay there, fingers near his mouth, as if trying to guard his words. There weren’t many of them.

He missed his parents. “I miss everybody.” His eyes welled up. “My mom especially,” he said.

No, he didn’t remember the murder, he said. He shook his head, looking miserable. “I think about what I done every day. I’d do anything to take it back. I’m sorry for the pain I caused the victim’s family,” Morgan said. “But I don’t remember nothing.”

How could he not remember? He’d killed an innocent woman; he’d demolished the lives of Trbovich’s children, who would spend more than 10 anguished years attending his criminal trials, seeing the gruesome crime scene photos, hearing the details of the murder again and again, constantly reminded of her last minutes.

He’d wounded his family; ruined his life; and haunted even his lawyers and jurors, who had to stare at autopsy photos and more. It was hard to believe he couldn’t remember the horror when he was the one who created it.

And yet court testimony backed him up. Morgan’s lack of recall was so profound that one of his public defenders—desperate for information so he could mount an insanity defense—hired a hypnotist to pry out some details.

“I wish I hadn’t of hurt my family,” Morgan said. He hated it that his parents suffered, sitting through his criminal trials and legal appeals.

Morgan’s father died before the start of Morgan’s third trial, in 1985. His mother died of cancer the month after the trial, after hearing her son condemned a third time. The Palm Beach Post noted her death in a small item that called her “the mother of three-time convicted murderer James Morgan” and said nothing else about her life. Morgan didn’t hear from his siblings after his parents’ deaths.

Since his time on death row, 17 fellow inmates had been executed. “You know when it happens because the lights flicker,” he said. The state power company didn’t provide electricity for executions, so the prison used an on-site generator for the 2,000 volts. The lights blinked when the generator powered on. “It’s not a good feeling,” Morgan said.

Do you have hopes you’ll get out?” I asked. He paused long enough for me to wonder if he was going to answer. “I never did have too many hopes about anything,” he managed.

Not long after, the interview time was up.

There was no way I could tell if he’d changed since he was 16. Morgan was polite and remorseful. But more than anything, he was dazed.

But If I wanted to know whether he could become a different person, I’d need to see him in the future. And I wasn’t sure he had one.

THE LAW

Morgan and the other death row teens around the country were part of a uniquely despised group of teenagers who, because of racial bias, prejudice, retribution, revenge or other reasons—none of them scientific—were singled out for the most extreme punishment.

Typically, they were poor. “One searches our chronicles in vain for the execution of any member of the affluent strata of this society,” as U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas once put it.

Among dozens of factors, teen offenders lived, died, or suffered depending on whether they had good lawyers or lived in the right time period. If they were 15 and committed murder in the 1970s, like Wayne Thompson in Oklahoma, they could be sentenced to death. A 15-year-old who murdered after 1988 could not be condemned because of Thompson’s successful U.S. Supreme Court case, which abolished capital punishment for pre-16-year-olds.

After 2005, the line of demarcation was 18. The high court that year ruled in Roper v. Simmons that it is unconstitutional to give a death sentence to people who were minors at the time of their crime. Juveniles are inherently capable of reforming themselves, the justices decided. They aren’t likely to have an “irretrievably depraved” character, because their character isn’t fully developed yet.

The decision ended a practice that had survived in the country for more than 350 years and resulted in more than 360 deaths (see sidebar). Now, the court was saying all those executions were wrongheaded.

“The juvenile death penalty is built around the premise that these offenders are hopeless and will never lead decent lives, and we might as well take them out,” said retired law professor Victor Streib, one of the world’s leading authorities on capital punishment of juveniles, who was a co-counsel for Thompson v. Oklahoma.

“The very nature of children is that they’re never hopeless,” Streib said. “To say that they can never be rehabilitated and they can never change—that is always wrong with kids.”

Morgan, for his part, was saved by four legal appeals to the Florida Supreme Court. In each case the high court reversed his death sentence, finding that the trial court made serious errors. In all, Florida spent 18 years and probably more than $1 million in its effort to execute Morgan, as Streib once estimated.

Morgan’s first trial was a do-over because the proceedings were split into an insanity and a guilty phase, which was unconstitutional.

Attorney Michael Salnick represented Morgan in 1984, the second appeal: He argued that the trial court improperly denied Morgan an opportunity to present an insanity defense. The justices agreed and remanded again.

In Morgan’s third trial, jurors weren’t allowed to hear medical experts testify about what Morgan said while hypnotized, the key to his insanity defense—another reversal followed.

By 1994, the fed-up Florida Supreme Court ended the cycle, having found that the fourth trial was flawed, too. The court commuted Morgan’s sentence to life in prison, meaning he would serve 25 years minimum and, at least technically, get a chance of parole.

Salnick, based in West Palm Beach, is one of the few people who stayed in touch with Morgan. He’s been in contact with him on and off ever since handling the appeal, when Morgan was in his early 20s.

“James was always respectful,” Salnick recalled. “He was calm. He read the Bible. Whoever he was on the outside, he wasn’t that person on the inside.”

Since speaking to me about Morgan last year, Salnick has decided to represent Morgan again for what he hopes could be a resentencing.

“I am so happy to be able to attempt to assist him,” he wrote in a Jan.15 email. No action has been taken yet, but he said he and Morgan settled on a fee. “I had to charge a retainer, so God bless him, he sent me a stamp and we were even.”

THE WALKING DEATH SENTENCE

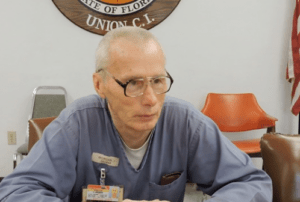

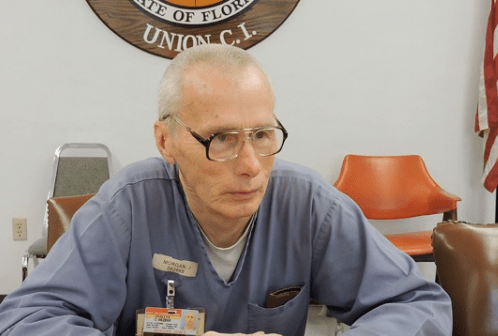

It is March 2015 when I meet Morgan again. I’m in a large, sunny hearing room setting up a camera, and I’m certain I’ll hear him arrive, jangling with metal like last time. Then I look up, and he’s already through the door.

He isn’t wearing shackles, or even handcuffs. He ambles up to me and gives a tentative smile. He is 54 years old, with the thin lips and weary presence of a much older man. He’s been behind bars for 39 years.

Morgan’s hair is silver, and he’s wearing prison blues and dark-framed, over-size glasses that reach a third of the way down his cheeks. A correctional officer pops her head into the room and says, “Here’s your inmate,” and leaves.

Morgan’s current home is Union Correctional Institution, up the road from Florida State Prison. We sit on leather chairs at a long wood table. Birds gabble outside the windows. Morgan sits across from me, occasionally raising his hand to his face, the way he did when I first met him 28 years ago.

This time it has nothing to do with guarding words. He talks slowly, but he doesn’t stop for nearly three hours. He hasn’t seen or heard from a relative in 20 years. Almost no one has visited in decades.

How have you survived? I ask.

“Have I? I dunno,” he says.

He spent his entire young adulthood—from age 17 to 34—on death row: Dec. 30, 2015 was the 38th anniversary of his death sentence. Now he lives in an “over-50 camp” for the “elderly.” The Department of Corrections calls inmates elderly at 50 because they age quickly, owing to poor health care before prison, and to poor health care inside it, human rights activists would add.

Morgan tells me straight out that he’s a different person than the teenager who arrived in ’77.

“Am I better than him? Yes. Can I change the mistakes he done? No. Am I sorry for what he done? Yes. But I ain’t the same person no more. That sixteen-year-old kid is dead,” he says. His voice trembles. “That sixteen-year-old kid died a long time ago.

“The trouble is, some people see prisoners as the animal they arrested,” he goes on. “They see you as the animal they put in prison.

“I sometimes I wonder if I would’ve been better off being executed. Because the only difference between being on death row and being out here is having a walking death sentence. That means never getting out of prison,” he says. “It means being in a parole system that doesn’t wanna parole nobody. Especially an ex-death row inmate or people with a life sentence.”

By the time the Florida Supreme Court took Morgan off death row in 1994, he was already in his 30s. Now he had a new survival challenge.

For his entire adult life he’d lived alone in a single cell and barely left it aside from brief showers and a few hours a week in an exercise yard. (He played volleyball: “Basketball is too violent.”)

Now he was in the general population. His new cell was only slightly larger than the one on death row, and he had to share it with another prisoner. He was in rec yards and chow halls with crowds of men. He saw fights and a few stabbings. He got in fights himself, decades ago. “But I matured.”

In the past 12 years he went a decade without a disciplinary report, but he recently got two DRs, he says. One was for “passing a magazine or book or something” from one cell to another; the other was for lying to staff about it, “like a dummy,” he adds. “The correctional officer was right to give ’em to me.”

Death row, in one way, had some happier times. In 1989, while in county jail awaiting his fourth trial, Morgan, 28, married Rita Runge, 26. They met through a “looking for pen pal” ad in a tabloid. For two years, while the marriage lasted, there was a steady visitor at the prison for him, unlike anything before or since. “I understood the divorce,” Morgan says. “She told me she can’t live her life any more without knowing what’s gonna happen in the future.”

It is an awful moment. I had tried to contact every possible person in Morgan’s life to ask about how he changed over the years, including his siblings, who didn’t respond to phone calls, and James Hitchcock, his former death row neighbor, still on the row for a murder he committed when he was 20.

Hitchcock taught Morgan how to read and write, he explained to me in a letter. The men lay side by side on the floor, with the wall between them, and Hitchcock held a primer through the bars so Morgan could see it and sound out the letters.

But when I tried to reach Rita Runge, all I found was an online obituary that said she died in 2011. I decide, reluctantly, to tell him about it.

He clears his throat and can’t talk for moment. He’d like to see the obituary, he says, and asks me to send it to him.

He got used to thinking about dying on death row, he says, after staring at the table for a while. “It’s like having a job–getting up every morning and going to it, right? You get up every morning, you realize you’re on death row and the chances are you’re gonna die.

“Compared to then, when I was on death row—am I more competent? Yes. Am I more aware? More educated? Yes. Do I want to go out there and make a life for myself? I would like the opportunity to.”

Do you think you have enough remorse? I have to ask.

“I look in the mirror every morning and have to face the fact that I took a human life. And … I can’t even begin to express,” he pauses again. “I don’t even know what I could say to ’em, except, ‘I’m sorry.’ I can’t blame the victims for wanting me dead.”

“I’ve paid almost 40 years for my mistake,” he says. “They can make me pay for the rest of my life. And I’m not saying they would be wrong. But at some point you gotta give someone the opportunity to show that he’s changed. Unless you got proof that we’re a threat to society, give us a chance to prove ourselves.”

“But no one wants to take a chance that an inmate might murder someone again,” I say.

“I’m not going to hurt anybody. The other old people in the prison are like that, too. We’re too old to go out and commit crimes. We’re harmless to the public.

“Guys in here is 70, 75 years old—they can hardly get around anymore. I’m blessed because I’m still physically capable. But I don’t know what next year holds.

“If I’m physically disabled,” he says, “and I can’t hold a job, and I can’t take care of myself—then there’s really no reason to get out of prison.”

It’s one of his biggest fears. “When they’re old, the majority of guys in here, they just stop trying to get out. I don’t want to be one of them. I want to get out!”

Today he works at the tag factory, making Florida license plates. He’s held past jobs pouring cement, working in the kitchen, and doing maintenance and construction work.

I mention that it can be hard out there. Paula Cooper, one of the only death row teens to win parole, was sentenced to death for a murder in Indiana when she was 16. She was released in 2013, was engaged to be married, had a dream job, and was beloved by friends and coworkers. But she couldn’t forgive herself for her crime. She committed suicide in May 2015.

“I don’t know,” Morgan says. He doesn’t seem to take in the story. “People say it’s harder getting out than it is getting in. And maybe some of that is true. But I don’t think it’d be that difficult.”

The last time Morgan was out in public was at his father’s funeral in 1985. He was in county jail for his third trial at the time and officials let him attend.

The whole family was there, but the guards didn’t want Morgan to get close to anyone. “I mainly wanted to see my mom,” Morgan says. His eyes tear up. He adjusts his glasses and clears his throat. “They let me stand next to her,” he says. It was the last time he saw her or any other relative.

He went from his parents’ home to a prison cell. He doesn’t know about the internet, or Walmart, or spending a day without having someone tell him what to do. Everything outside of prison would have to feel alien to him after this many years. The transition would be unimaginable.

Maybe in the end what Morgan represents is a problem that’s unimaginable. No one can undo the harm to the Trbovich and Morgan families. No one can repay Morgan or other teenagers for their years on death row, which—as it turns out—is cruel and unusual punishment, akin to torture, the U.S. Supreme Court has said.

For now, Morgan says he reads the Bible, and goes to church services and AA meetings, he says. “But I know I can go out there if they gave me the chance.”

He doesn’t know exactly what he’d do first if he got freed. But he thinks he’d go to McDonalds, then to the beach. And he’d like to see the St. Lucie River near his home.

He makes customized license plates these days that say “save the manatee,” and those are his favorites. When he was a kid, he saw a manatee once in the river.

“You gotta love manatees,” he says. “They’re so harmless. They’re so innocent.”

TIME OF DEATH

In 1642, Thomas Granger, 16, was hanged in Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts, for having sex with a mare, a cow, and some goats. It was America’s first documented execution of a child offender and the debut of the juvenile death penalty. The practice would end 363 years later after the deaths of at least 366 child offenders—people under the age of 18 at the time of their crime.

The youngest girl to be executed was 12-year-old Hannah Ocuish, a member of the Pequot tribe, who was hanged in Connecticut in 1786 for murdering a six-year-old white girl.

James Arcene, a Cherokee, was the youngest ever to be condemned. He was hanged in Arkansas in 1885 for a murder-robbery he helped commit when he was 10, and was executed 13 years later.

In 1944, African-American George Stinney Jr. was electrocuted in South Carolina when he was 14 years old, making him the youngest person executed in the 20th century. Stinney was put to death less than three months after his arrest for allegedly murdering two white girls. An all-white jury deliberated 10 minutes before finding him guilty. (In 2014, a South Carolina court exonerated him posthumously, finding that he’d suffered an egregious miscarriage of justice.)

In 1964, Texas executed James Echols, black, the last teen offender to get the death penalty for rape. Echols was put to death at 19 for raping a white woman when he was 17.

After Echols, juvenile executions stopped for 21 years. The death penalty’s popularity was waning and states retreated to the sidelines, waiting for courts to rule on various legal challenges to the punishment.

Abolitionists argued that the penalty was meted out to a fractional number of teens who—for reasons of discrimination, caprice, fear, rage, tough-on-crime politics, or inchoate loathing—were punished far more harshly than thousands of other offenders who committed equally horrific or worse crimes.

By 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Furman v. Georgia shared some of those views. Death sentences for all age groups were imposed so arbitrarily—so “wantonly” and “freakishly” as Justice Potter Stewart put it—that they violated the Eighth Amendment, the court found. The ruling in effect struck down death penalty statutes nationwide, at least until states crafted new laws that would pass judicial muster.

In all, 37 states and the federal government put the punishment back on the books; only a few years after the Furman ruling, teenagers began arriving on death row again. The modern era of the death penalty had begun.

This time, it would last 31 years. The 2005 U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the penalty in the landmark case Roper v. Simmons, finding that it was cruel and unusual punishment. For some young offenders the ruling was a lifesaver. For others, it came too late.

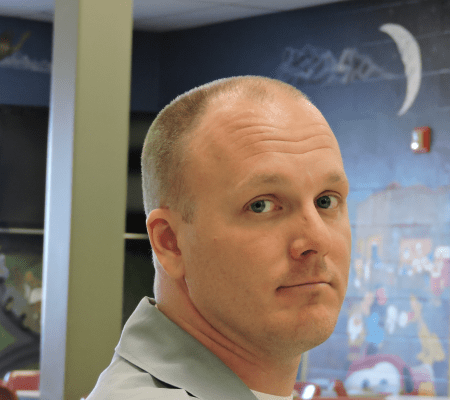

Christopher Simmons, shown in the” visiting park” at Southeast Correctional Center in Charleston, Missouri, in March, 2015.

Simmons, 39, is the teenage offender whose Supreme Court case, Roper v. Simmons, abolished juvenile capital punishment in the country and spared the lives of 72 juvenile offenders then on death row. All of them were re-sentenced, most to life in prison with very little or no chance of parole.

Simmons was 17 when he murdered a woman who lived in his low-income neighborhood in Fenton, a suburb of St. Louis. In 1993, he and a 15-year-old friend decided to burglarize Shirley Crook’s house at night while she was sleeping. After they broke in, Crook woke up and recognized Simmons. The teens tied her up, put duct tape over her face, drove her to a nearby state park, and threw her from a railroad bridge into the Meramec River, where she drowned. Photo by Amy Linn.

* * *

BY THE NUMBERS

The juvenile death penalty in the modern era

Number of juvenile offenders executed between 1974 and 2005, when the U.S. Supreme Court abolished the punishment: 22.

Number sentenced to death: 226

Percent executed who were African American: 50

Percent of African Americans in population as a whole: 12

Number of executed who were white: 10

Who were Hispanic: 1

Of all executed teens, percent whose victims were white: 81

Approximate number of former death row teens who are behind bars today, re-sentenced to life in prison with little or no possibility of parole: 187

Who are almost 60 years old: 9

Number of juvenile offenders exonerated: 3

Years that juvenile exoneree Kwame Ajamu spent in an Ohio prison for a murder he did not commit: 28

That Leon Brown spent in a North Carolina prison for a rape and murder he did not commit: 30

Male juvenile offenders sentenced to death: 221

Female: 5

Number of executed who were female: 0

Percent of juvenile offenders executed in Texas: 60

Percent executed in Texas, Virginia, and Oklahoma combined: 81

Year the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for offenders younger than 16: 1988

Aside from the United States, number of United Nation members today that have refused to ratify the 1989 U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, which bans the juvenile death penalty and provides widespread protections for children: 0

According to the Supreme Court, number of countries other than the United States that officially sanctioned the juvenile death penalty in 2005: 0

Percent on death row in 2005 who were people of color: 66

Estimated percent of death row inmates of all ages who experienced at least one (and up to 11 or more) of the following: physical, sexual, psychological abuse; neglect, poverty, trauma, mental disorders, illiteracy, substance abuse; intellectual or neurological impairments, head injuries; witnessing family violence; parental substance abuse or mental illness; death or absence of parent: up to 95

SOURCES:

Law professor Victor Streib: “The Juvenile Death Penalty Today” and Death Penalty in a Nutshell

Michael Radelet, Facing the Death Penalty

The Death Penalty Information Center

The National Registry of Exonerations

Amnesty International

Amy Linn is researching death row teenagers during her Alicia Patterson fellowship year.