October 14, 2015

It was the perfect campsite, a place where the five kids in the Jaeger family could skip stones in a drifting river and wake up to views of the Montana Rockies.

Marietta Jaeger and her husband, their three teenagers and two grade-schoolers in tow, had driven 2,000 miles from their suburban Detroit home to reach the spot at Missouri Headwaters State Park. The swath of land near the tiny Montana town of Three Forks gave way to the hardscrabble Horseshoe Hills, some 50 miles northwest of Bozeman.

It was June 1973. The park was the first stop in a long-planned dream vacation, their first family camping trip. And everything was falling into place. They’d even snagged a prime site by the riverbank, complete with a picnic table under shade trees.

When it was time for bed, the younger kids scrambled into a tent and cocooned themselves in sleeping bags. Heidi, 13, snugged in next to 7-year-old Susie, the coltish, brown-haired baby of the family, whose natural exuberance was balanced by a surprising thoughtfulness for her age. At one point in the night the two girls woke up and talked before settling back to sleep.

David Meirhofer, 24, heard them. He was a contractor from the nearby outpost of Manhattan, a member of the town’s bowling team and someone known, if he was known at all, as a loner. He’d been scouting the campground and happened to walk by the tent when Susie and Heidi were talking.

One of the girls sounded young, he noted. He waited until everyone was asleep. Then he slashed open the tent, grabbed Susie, quickly choked her into unconsciousness and dragged her out. No one stirred.

Heidi woke before dawn, startled by cold air drifting in through the tent hole. “She sat up and looked around,” Jaeger tells me on a recent day. “And Susie wasn’t there.”

‘None of it seemed real’

It would be 15 months before the Jaegers knew what happened to their youngest daughter. “I kept thinking that it couldn’t possibly be happening,” says Jaeger, now 77.

We’ve met at a busy coffee shop on a recent day near her home in Missoula, Montana, about 180 miles north of where Susie was taken. She has curly white hair and the startlingly blue eyes that stared into so many television cameras after her daughter’s disappearance. “None of it seemed real,” she says.

Marietta’s parents were also at the campground; they’d joined the trip to see the grandkids. Now all of them sat stunned, day after day, trying to understand the devastating events.

The picnic table by the river became the staging ground for television interviews. Marietta, then 35, spoke carefully, flatly. “We won’t go home until we’re a whole family again,” she told reporters.

Jaeger and her husband, Bill, had been asleep in her parents’ truck when Heidi wakened them, shouting that Susie was gone. Bill raced to Three Forks to find police.

Within hours, the area was swarming with officers and search parties, scouring the landscape on foot and by horse, boat and plane. There was a single hopeful moment: The FBI got a credible call from a man who demanded ransom and said he’d phone back with instructions for the handoff. He never did.

The turning point

“Then they started dragging the river by the campsite,” Jaeger says. The terror was overwhelming. “They kept bringing the net up, and each time, I didn’t know if Susie would be there.” All day she imagined what she’d do if the FBI brought her the kidnapper. “I knew I could kill him with my bare hands.”

Jaeger is a devout Catholic. Her entire life she’d been taught to “love your enemy.” And now she wanted her enemy to hang.

“That night I had an argument with God,” she says. “I told him, ‘Susie is an innocent, defenseless little girl, and I’m her mother, and it’s only natural that I should want to hurt the man who took her.’” How was she supposed to make it through this?

Her answer changed her life. “I realized that if I gave into rage and fury and that desire for revenge it would consume me, and I’d never be any good for anyone. When we live with rage and bitterness, we destroy ourselves — we give the killer another victim.”

Somehow she had to find compassion, for the sake of her family and for the sake of her missing child. If she ever got to speak to the kidnapper, and showed him kindness, he’d treat Susie better or maybe let her go, Jaeger told herself. If she let the kidnapper know she didn’t want him executed, he might turn himself in.

Day by day she trained herself to feel concern for the man who, finally, would be revealed as Meirhofer. He confessed to the unspeakable. And Jaeger did the unimaginable. She forgave him.

Survivors who are against the death penalty

When you ask Jaeger to tell her story it’s impossible not to apologize. “I’m sorry to make you relive this,” I say to her during several days of talking in Missoula. I’m taking notes and at certain points my pen stops moving, as if it’s decided on its own that the facts are too horrific to record. “It’s OK,” Jaeger reassures me. “I’ve been telling this story for 40 years.”

She’s told it in towns across the country; at state legislatures and universities; at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in Geneva; and in Rome, Japan and South Korea. She’s described it to media outlets from the Bozeman Chronicle to “Good Morning America.”

She’s done so as one of the forerunners in one of the most unlikely and increasingly visible anti-death penalty campaigns — led by survivors of violent crimes.

Adherents tell their stories, over and over again, to try to convince the world that reconciliation promotes healing. Taking revenge prolongs and multiplies anguish for the victim’s family and the murderer’s, they say. Retaliation multiplies the violence in the world, a Gordian knot of evildoing-to-evildoers that has been strangling us since the dawn of man. Mercy, in this view, is the best way to unravel the threads.

On June 19, only two days after a racist white gunman shot and killed nine people during Bible study in a historic black church in Charleston, S.C., heartbroken relatives of the victims offered him forgiveness. “We will not let hate win,” the family members told Dylann Roof at his bond hearing.

In April, Bill and Denise Richard, whose 8-year-old son died and 7-year-old daughter lost her leg in the Boston Marathon bombing, asked the Justice Department to stop seeking the death penalty for the bomber, for wrenchingly practical reasons. Pursuing the punishment for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev could bring decades of legal appeals and give a continual spotlight to a murderer whose actions killed three people at the marathon and injured more than 260. It would “prolong reliving the most painful day of our lives,” the Richards said.

In May, before Tsarnaev was nevertheless condemned to die, members of the abolition group Murder Victims’ Families For Human Rights spoke to a small gathering at a Boston church near the site of the marathon bomb blasts. Bud Welch, a founding board member, told the crowd about losing his 23-year-old daughter, Julie, who died along with 167 others in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

After the attack Welch says he descended into months of “self-medicating” with alcohol. He just wanted to see bomber Timothy McVeigh dead. But he eventually realized he opposed the death penalty, in keeping with his daughter’s own belief that it was immoral. Hatred and revenge killed Julie; he did not want to live by it, he says, a decision he’s since described at speaking events around the world. After McVeigh was executed in 2001, Welch found solace by befriending McVeigh’s bereaved father.

Abolitionists tell similar stories via social media and the web (Google “forgive murder” and you get 23 million results). The organization Journey of Hope: From Violence to Healing — co-founded in the early 1990s by Jaeger and fellow activist Bill Pelke — has toured 40 states nationwide and 16 countries overseas. Speakers include a woman whose father was stabbed to death in front of her and a man whose brother was executed by a Utah firing squad.

Pelke, a retired steelworker who runs Journey of Hope from his home in Alaska, lost his grandmother, a 78-year-old Bible teacher, in a brutal murder at her residence in Gary, Ind. Four teenage girls were charged in the slaying. When one of the teens, 15-year-old Paula Cooper, was sentenced to die in the electric chair, Pelke devoted himself to a campaign to save her life.

Forgiveness too

The overarching goal of the U.S. movement is to end the death penalty. For some advocates, the mission ends there. “They don’t want to have the murderer over for Sunday dinner,” as one advocate puts it. Not every story involves forgiveness.

But many do. In Tulsa, Okla., Edith Shoals, 67, is a victims’ advocate for the Oklahoma Department of Corrections and, on the side, organizes support groups for women whose children were murdered. In 1992, Shoals’ daughter Lordette, an 18-year-old college student, called Shoals from a pay phone and was murdered in midconversation, shot in the back by a carjacker.

“Grieving’s not a big enough word for what happens,” says Shoals. “But if you don’t forgive, it eats you up from the inside out.”

Overseas, the U.K.-based Forgiveness Project, a secular organization founded by former freelance journalist Marina Cantacuzino, offers so many reconciliation stories from around the world — told by both victims and perpetrators — that you can choose them in a drop-down menu organized by type of violence: gun crime, knife crime, war crime, sexual abuse, racism, neo-Nazism and more.

There are no rules for forgiveness, Cantacuzino says on the group’s website: “It is first and foremost a personal journey.” The goal is to “build understanding, encourage reflection and enable people to reconcile with the pain.”

In a completely different realm, psychological journals and blogs are describing forgiveness as a health booster (albeit with much scientific fuzziness: Beliefs don’t lend themselves to double-blind studies). There’s even a “forgiveness app,” which sounds like the one thing about the issue that could be vaguely comical until you read that its creator is an Australian woman whose father was brutally murdered.

Jaeger, for her part, had none of this to turn to in 1974, when she learned that Susie had died. Mercy groups didn’t seem to exist. That changed in 1976, when Marie Deans, a tireless advocate for death row inmates, launched Murder Victims’ Families for Reconciliation, today the longest-running victim-led abolitionist group in the country. Jaeger was one of the founding members.

Since then, Jaeger, Pelke and hundreds of others (hard numbers are impossible to come by) have spent decades joining abolitionist marches, rallies and speaking tours, alongside activists such as Sister Helen Prejean, the Catholic nun who wrote the book “Dead Man Walking,” later to become a hit movie starring Susan Sarandon.

Forgiving doesn’t mean forgetting, Jaeger reminds audiences. “The criminal needs to be punished, with life in prison if necessary,” she tells me. Compassion doesn’t let the killer off the hook. In her case, it reeled him in.

Severely mentally ill

On June 25, 1974, at 2 a.m. on the one-year anniversary of Susie’s kidnapping, the phone rang at the Jaegers’ home in Michigan.

“Is this Susie’s mom?” the caller said. “Well, I’m the guy that took her from you, one year ago to the minute.”

For 12 months Jaeger had been practicing compassion, and now, miraculously, she had it. “Is she alive?” she asked. “Is she safe? Can I have her back?”

“I don’t think that’s possible at this time,” the man replied.

He told Jaeger he was traveling with Susie and taking her to fun places like Disneyland. “It was obvious that he wanted to taunt me,” Jaeger says. She stayed calm and told him she was concerned about him. “I wish there was something we could do to help you,” she said. The words kept him on the phone for more than an hour, all of it tape-recorded by the FBI. At the end of the call, he broke down and cried.

“To be able to contain herself over an hour with the person that she viewed as the man who had her child — it was beyond belief,” FBI Special Agent Patrick Mullany, a lead investigator, said in one of many television shows about the case. “He starts out really trying to stick it to her, to where at the end of the hour, he was really sobbing.”

The call unlocked the case. It allowed the FBI to identify the kidnapper for certain — it was Meirhofer, who still lived alone in remote Manhattan. By this time he was the prime suspect in another hideous crime, the February 1974 murder of a 19-year-old Manhattan woman whose bones — more than 1,200 charred, chopped fragments of them — were uncovered at an abandoned ranch in the Horseshoe Hills, not far from the campsite where Susie was taken.

Jaeger, the FBI decided, might be able to make him betray himself or confess. They flew her back to Montana to confront Meirhofer face to face.

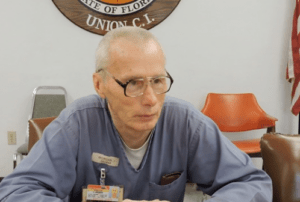

The first meeting took place in an office with Meirhofer’s attorney. Jaeger sat on a chair that the FBI artificially propped up so that she looked taller and more dominating. Meirhofer sat opposite, a slight man, somber, clean-shaved, with neatly combed, close-cropped dark hair, wearing jeans and a work shirt. “I know you took Susie,” Jaeger repeatedly told him. He denied it.

The next day she met him alone at his workplace. Sheriffs hovered outside in case he tried to hurt her. Jaeger says she could see that he was severely mentally ill; the FBI believed he was schizophrenic. Again, she pleaded with him. He wouldn’t crack.

But a week later, in a last phone call to Jaeger, he slipped up and described details that only the killer would know. Enraged that he’d incriminated himself, he yelled into the phone, “You’ll never see your child again.”

Authorities finally had what they needed to arrest him. And the evidence against him, in the end, was overwhelming. When investigators searched his home they found bloody sheets and body parts. Meirhofer’s confession came shortly after.

In 1967, when he was a senior in high school, he shot and killed a 13-year-old boy playing on a bridge near Manhattan, he told law enforcement officials. The next year he fatally stabbed a 12-year-old Boy Scout in a tent at the same campground where Susie was taken, at the same campsite, only yards from where she’d been lying.

Meirhofer wouldn’t discuss the multiple other unsolved child murders in Montana that police thought he might have committed. But he did admit to kidnapping and murdering the 19-year-old Manhattan woman, Sandra Smallegan, in February 1974, eight months after kidnapping Susie. He burned and scattered Smallegan’s remains at the abandoned ranch.

He took Susie to the ranch, as well. She was molested, strangled and dismembered, likely after a week, Jaeger says. A piece of her pelvic bone was found buried in a pit.

At 2 a.m. on Sept. 29, 1974, Meirhofer’s confession was finally over. He was given breakfast a few hours later. The guard offered him a towel to clean up. He hanged himself in his cell.

The right response to evil?

Meirhofer’s suicide was not a relief to Jaeger. The family went back to Michigan and began the painful process of rebuilding their lives. Bill Jaeger continued his work in the auto industry (he would die of a heart attack a little over a decade later). Marietta deepened her commitment to her ideals.

Forgiving is not a spiritual mulligan; it doesn’t give criminals a free pass, she coaches me in the basics. We’re talking for the second time, sitting in another Missoula coffee shop, and she is answering countless questions with unerring generosity. Executions do not honor the victim, she continues. “Susie was a sweet beautiful girl who deserved a more beautiful and noble memorial than a state-sanctioned cold-blooded killing.”

To share coffee with Jaeger is to enter a surreal world where, at the next table, people are joking about how they want to kill the waiter for bringing a latte instead of a cappuccino while right in front of you a mother is describing how she didn’t wish death on the man who murdered her 7-year-old.

What is the right response to evil? I have to ask again. People who have been taught about forgiveness from an early age — perhaps because of a spiritual background — might have easier access to the concept, I’m thinking. But for me, it’s a dark thicket without a bread crumb.

Revenge is sweet and mankind has a big sweet tooth, myself included. Some people in my family are victims of violent crime, I tell Jaeger. I haven’t forgiven one perpetrator in particular, in large part because the man never apologized.

Before arriving at the coffee shop today I found a 1983 Time magazine cover story about how Pope John Paul II forgave the would-be assassin who shot him four times. “Why Forgive?” the headline asked. That’s where I’m still stuck.

Some people believe no one can forgive on behalf of another person, I mention to Jaeger. The concept is at the heart of “The Sunflower,” a book by Holocaust survivor Simon Wiesenthal, who asks theologians, intellectuals, survivors and dozens of others a single question: “You are a prisoner in a concentration camp. A dying Nazi soldier asks for your forgiveness. What would you do?” Wiesenthal, who actually lived this moment, did not forgive the dying Nazi.

“I’ve heard the argument before, about not forgiving for someone else,” Jaeger says. “I understand how people might feel that way. But those weren’t my own feelings. I needed to follow my own journey.”

Her journey led her to meet Meirhofer’s mother years ago. They hugged each other, two bereaved women taking comfort. They refused to talk about the crime.

“I needed to stop thinking about how Susie died,” Jaeger says. She tells me about visiting Susie’s grave, and then has to stop for a moment to regain her composure. “I’m sorry,” she apologizes.

“This is what I live with,” she says, simply. And then she’s ready to tell her story again.

APF fellow Amy Linn, with Bloomberg Bureau of National Affairs, is examining juveniles with long prison terms. This article, prepared under her APF grant, appeared in The New York Times.