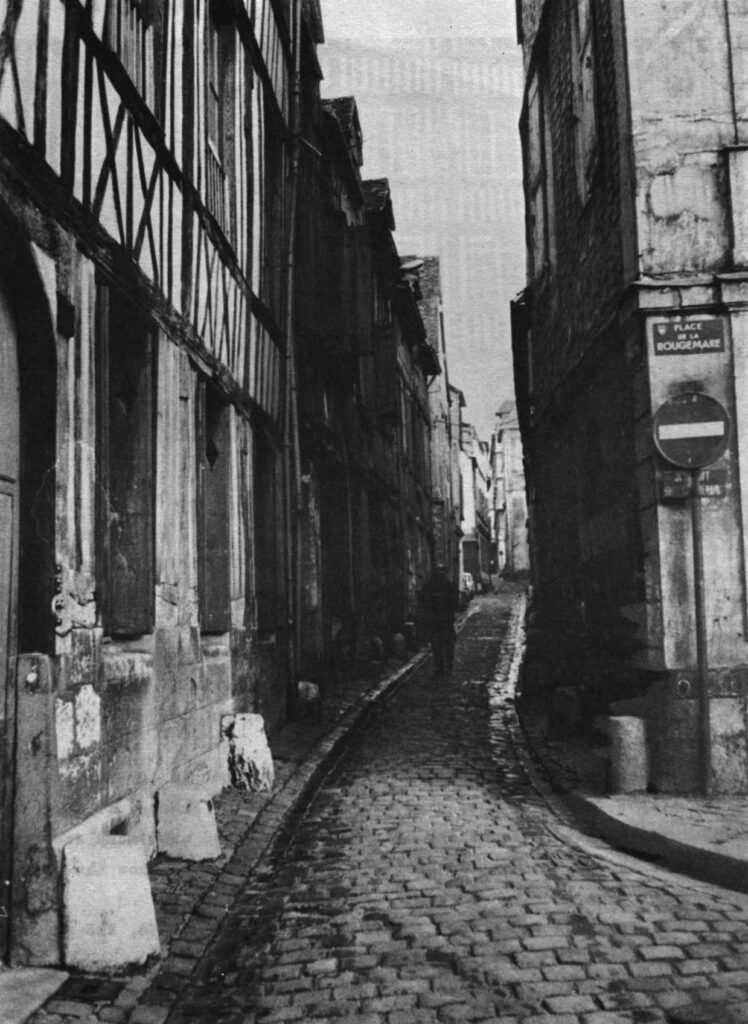

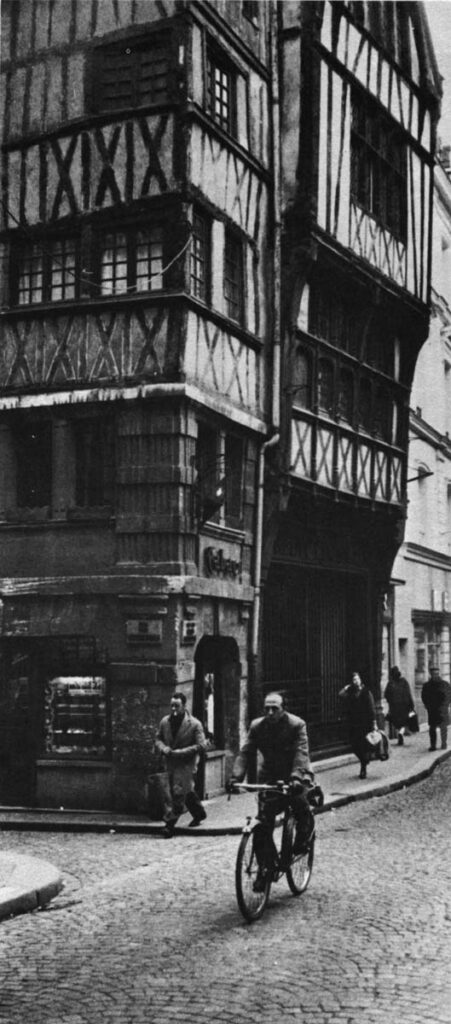

Rouen – William the Conqueror returned to Rouen to die. Joan of Arc was condemned and burned here. Along the medieval twisting of its cobbled streets, Rouen looks very much a part of its past.

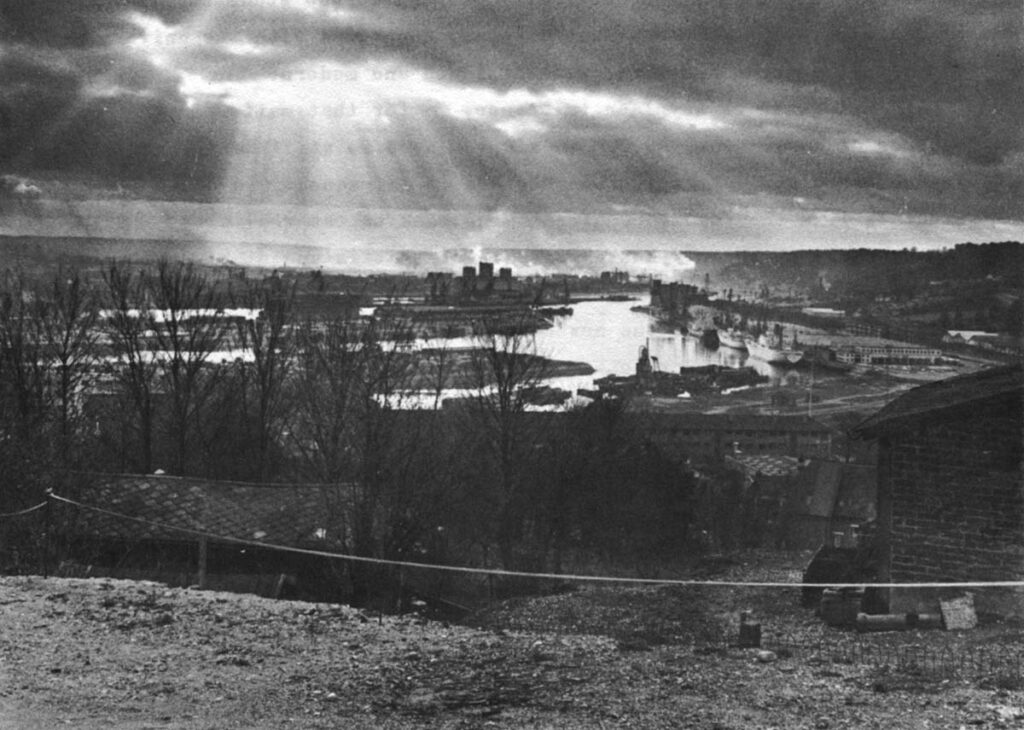

The harbor, too, is still the junction of Seine River barges and ocean freighters, as it has been for ten centuries. Great cranes now fill the skyline before the city’s steeples, but the mind’s eye fills in masts and spars.

Rouen has always changed. Change is written in the variety of the city’s facades. Now, like all the cities of France, it must change still faster. There are many more people and many more stores. The demand is for kitchens and toilets and cars, and somehow the city must supply them.

Also, Rouen was bombed. In 1940 and again in 1944, 225 acres of the city’s heart were leveled.

This piece, mostly pictures, is about what change does to a city’s style.

Downtown Rouen wears its past proudly.

Rouen has made some of the same obvious mistakes as every place. This is the first view approaching the city from Paris.

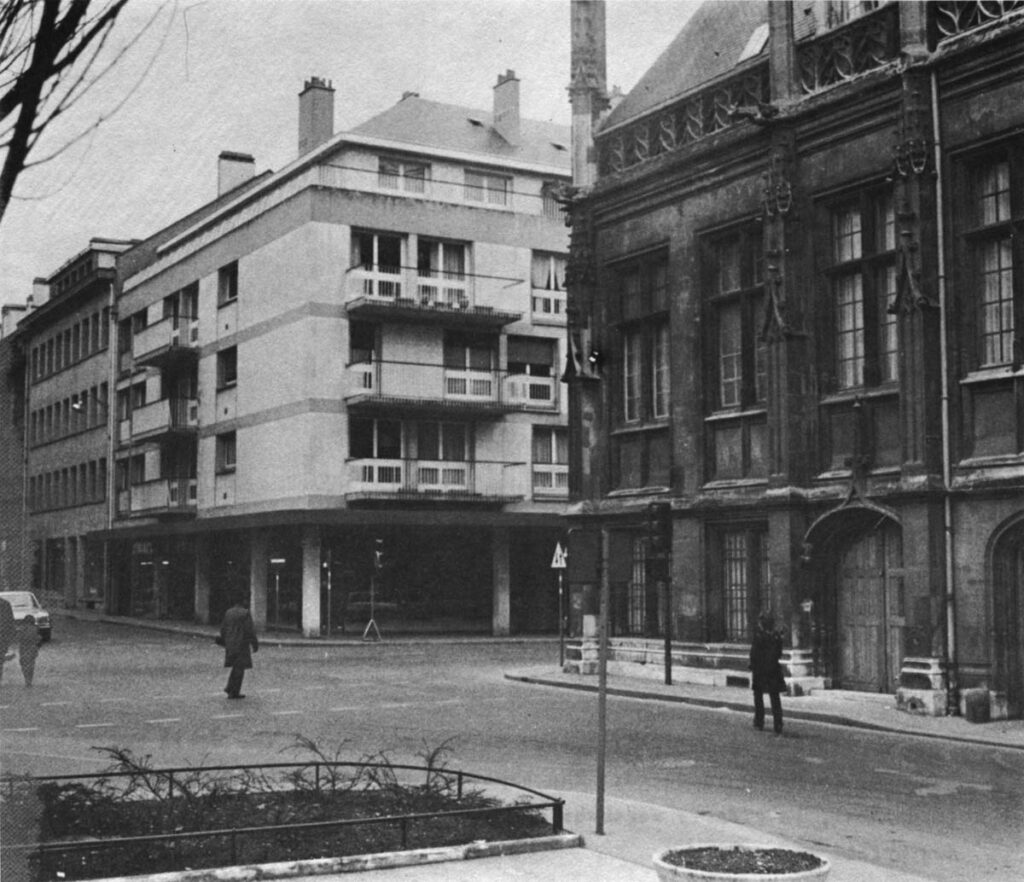

Rebuilding well in an old city does not mean putting up new buildings that look antique. This apartment block (left) looks fine next to the old Palais de Justice (right). Although the two buildings are as unlike in style as possible, they have the same relationship to the street, and the same overall mass. The variety of the scene is a continuation of the evolution of centuries. It is a happy compromise with the hideous expense of recreating the old, and it keeps the neighborhood lively and useful. Unfortunately, much of what distinguishes a city – its style – is not so easily classified historical and preserved.

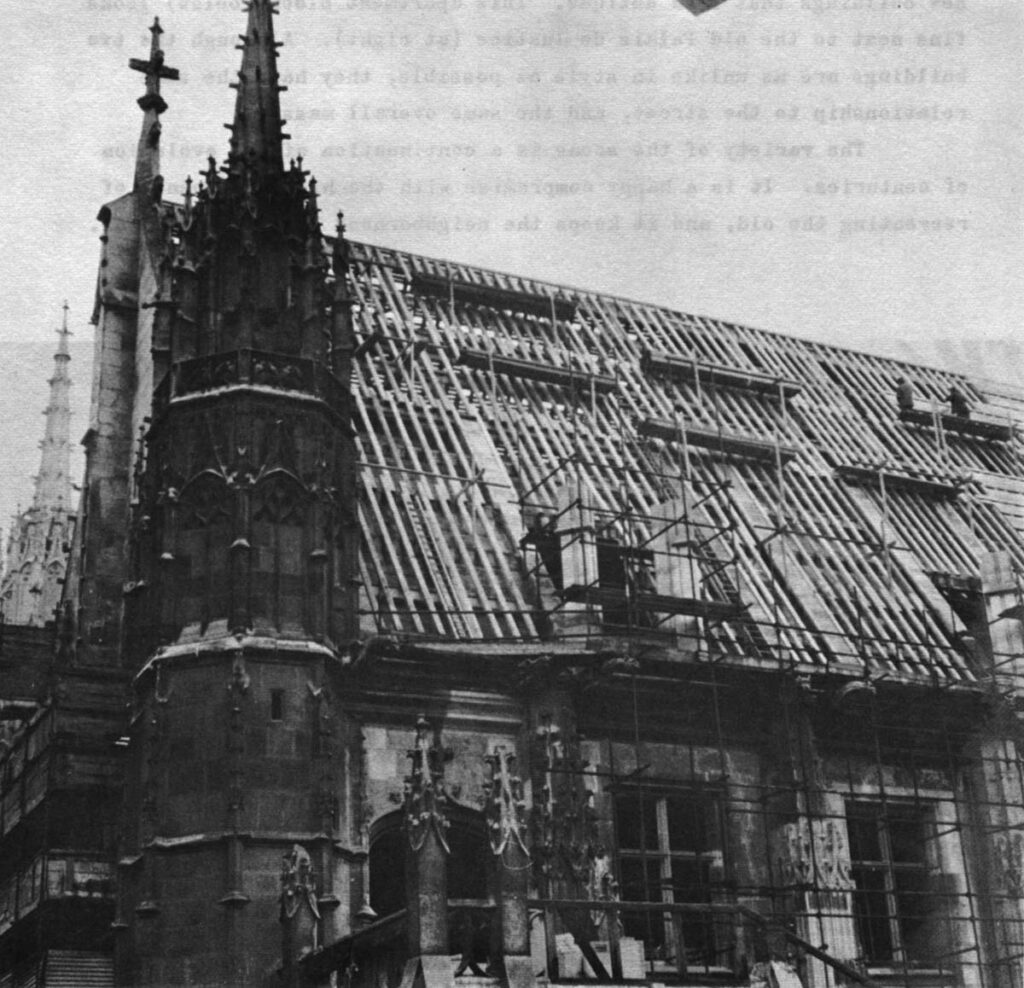

The Palais de Justice itself, damaged during the World War II bombing, is being restored. The expense, shared by the national government, is clearly worthwhile for a city’s, not to say a country’s, historical monuments.

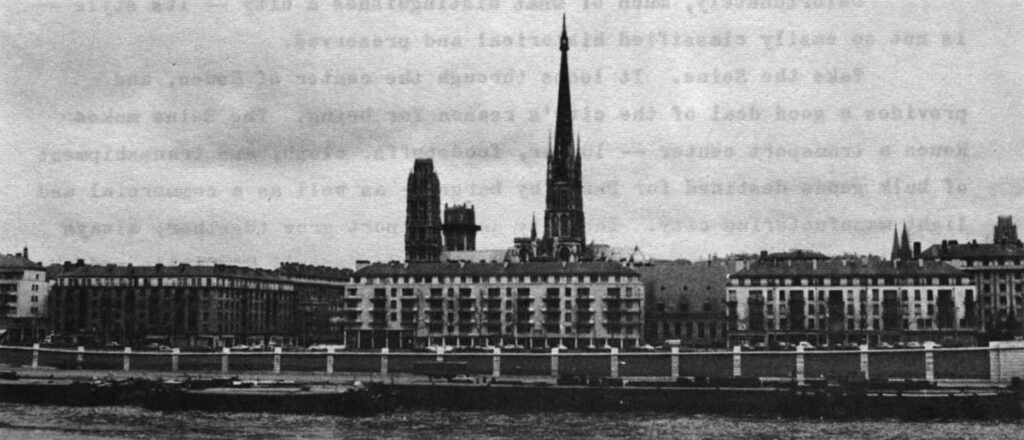

Take the Seine. It loops through the center of Rouen, and provides a good deal of the city’s reason for being. The Seine makes Rouen a transport center – lumber, foodstuffs, cloth, and transshipment of bulk goods destined for Paris by barge – as well as a commercial and light manufacturing city. The city and the port grew together, always mingled. The main square, now called Place du General de Gaulle and dominated by a statue of Napoleon on horseback, is only a few hundred yards from the river.

The last block of old buildings on the river-front is being demolished. Progress, no doubt, but what is visibly Rouen, not just any river town, is diminished.

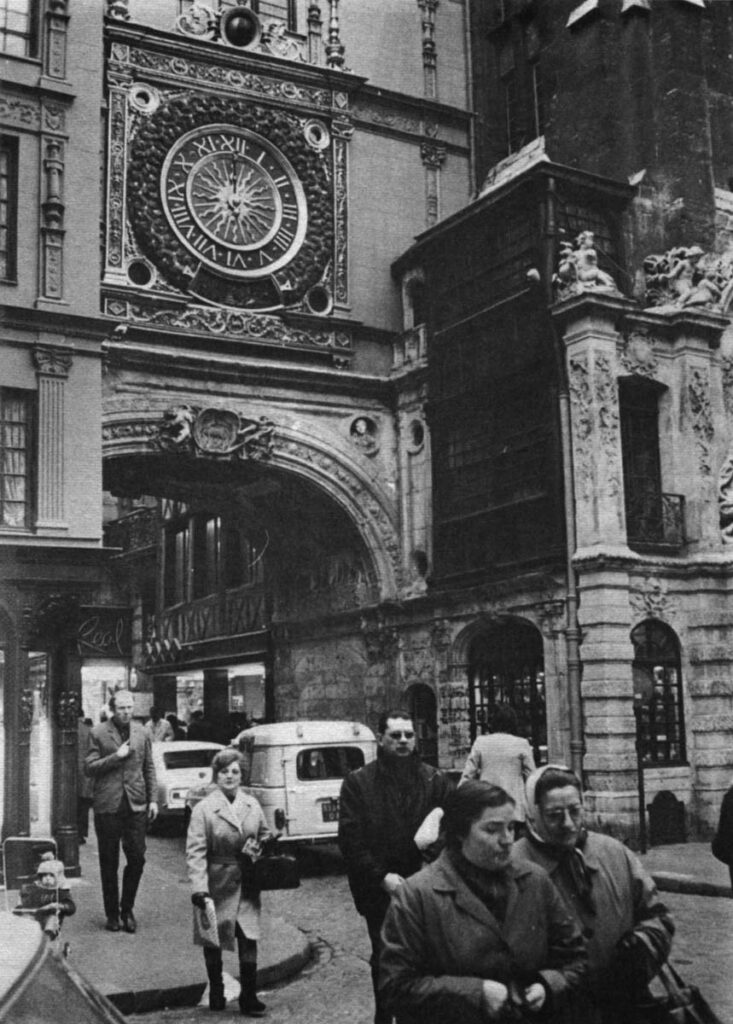

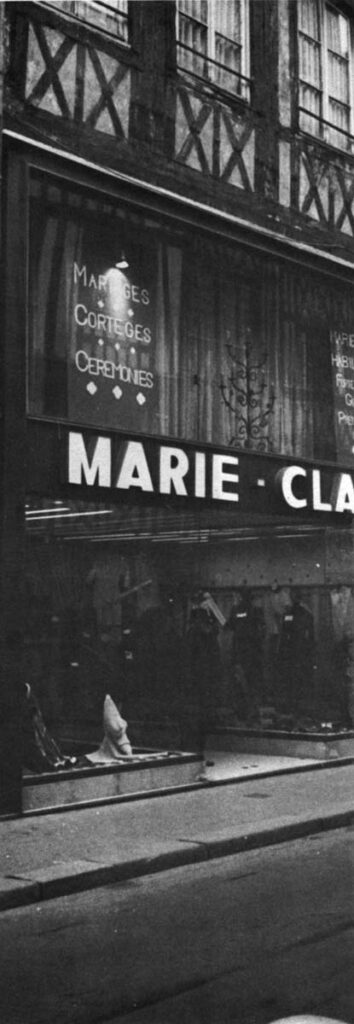

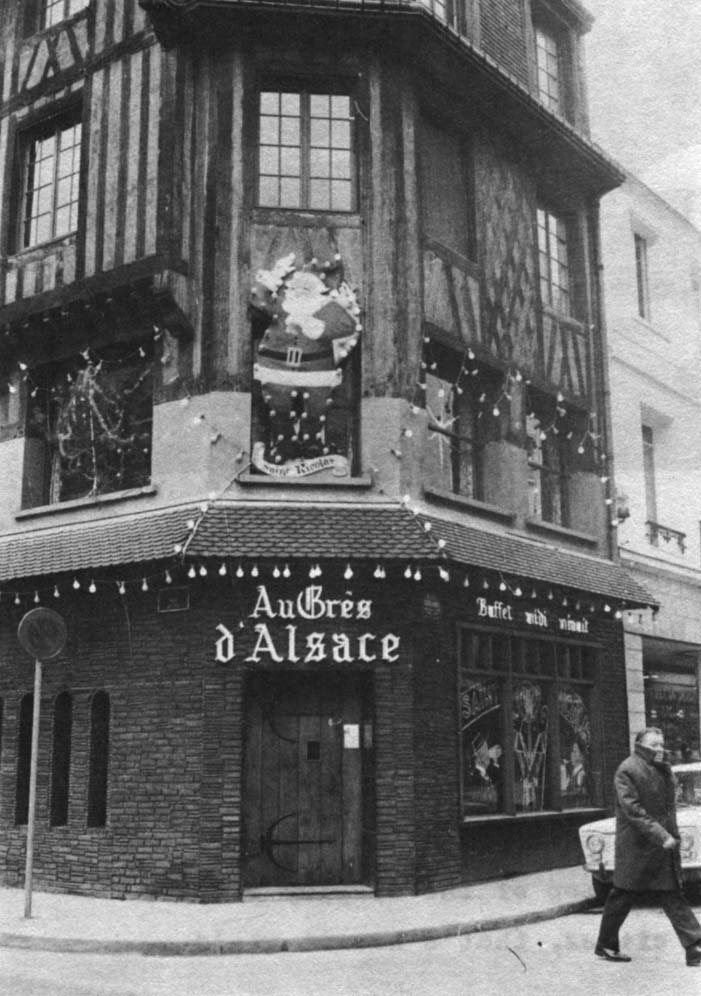

This is the gross clock of Rue du Gros-Horloge. It is the central feature of Rouen’s oldest, liveliest quarter. Here modern stores are moving into ancient buildings, gutting them, and rebuilding. The process is far more expensive than building from scratch. The result is also more stylish.

The results are not uniformly satisfactory.

Above are two illustrations of a sort of Gresham’s Law of architecture, demonstrating that the genuinely antique can look just as ersatz as the genuinely phony. Drugstore is a Champs-Elysees phenomenon now spreading across France. Almost everything is sold there, even a few drugs.

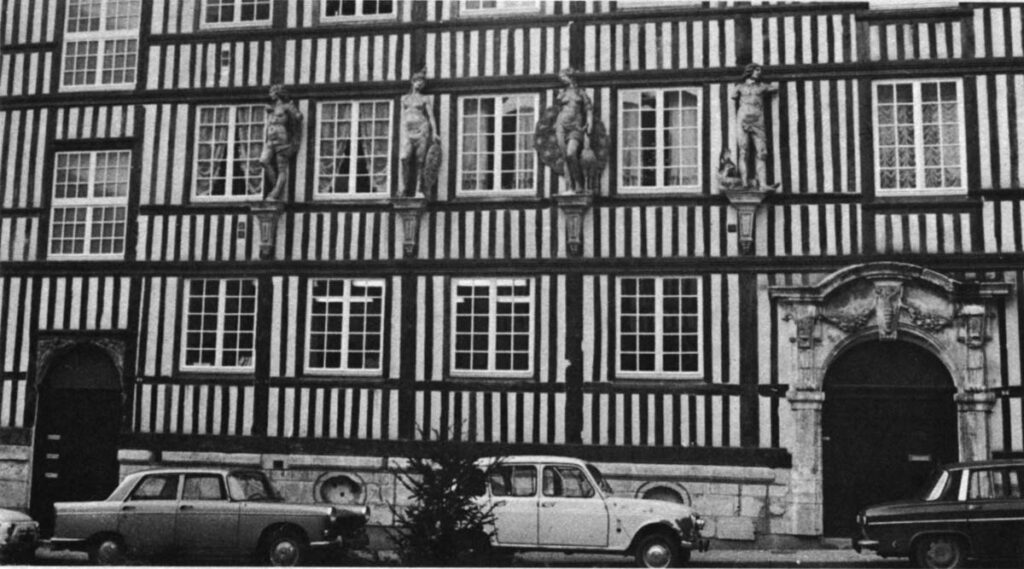

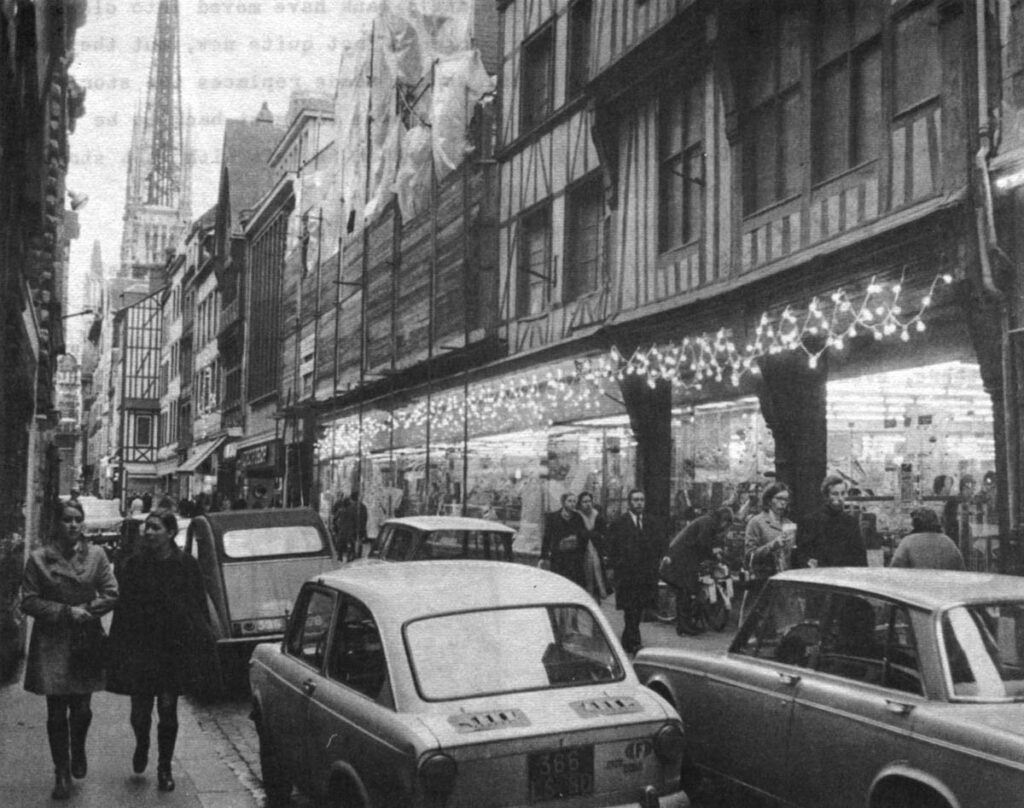

A little up from the clock on Rue du Gros-Horloge is an interesting facade. On a street where the pattern is of individual houses in vertical segments, the long horizontal sweep is clearly out of place. But several pillars show, and the display window is inset a foot from the overhead facades. The overall effect is all right. But imagine it with a great red Woolworth sign across the top of the display window, covering half the windows above. Most cities, that’s how it would be done.

The cars, of course, are what really dominate this photo. They are what is most likely to change old Rouen beyond recognition.

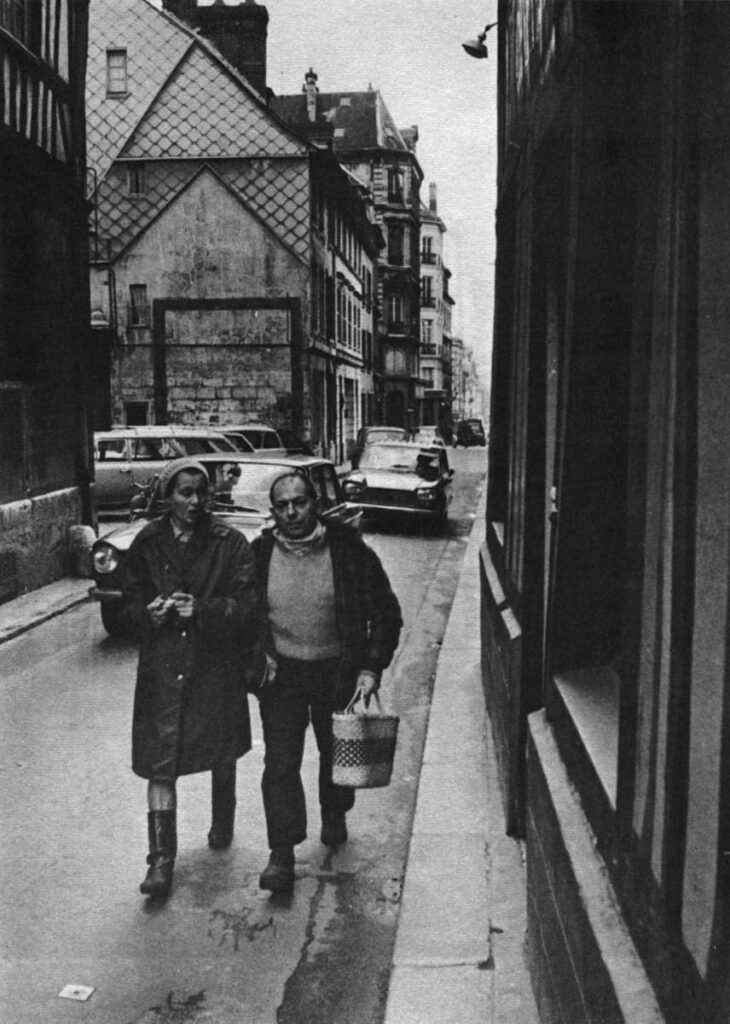

This is a typical enough Rouen street scene. There is no sidewalk, and there is no restriction on the use of cars. Pedestrians and drivers are discourteous to each other here, and it gradually becomes less and less pleasant to be a pedestrian. Yet the whole distinctive downtown section of Rouen is on a scale suitable only for the pedestrian. As a drive-in shopping center, it is clearly unsatisfactory. That is why the old downtown is gradually being nibbled away.

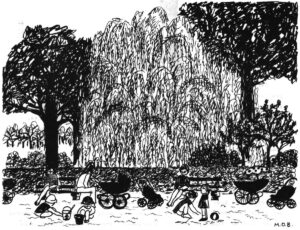

This is a photo of a lovely French square. Some half-timbered medieval buildings, some Second Empire ironwork, everything in nice proportion – a bar, two offices and many residences make an inviting city street scene. It makes you think of boules on a summer evening, perhaps, with girls watching from the windows.

It is also a photo of 11 automobiles, none of them at the time in use. The square has been redesigned to accommodate the autos better. The people are walking in the street. There is clearly no room to play boules.

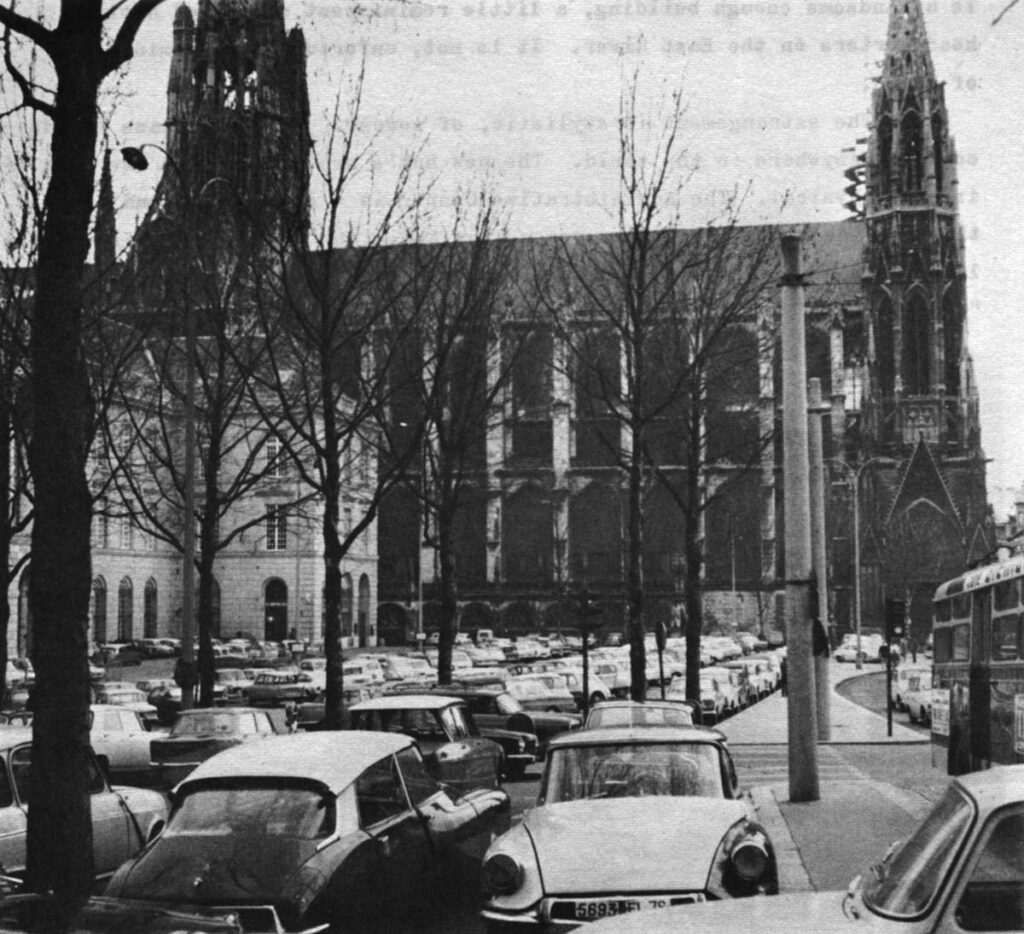

St. Ouen is one of the famous cathedrals of all France. The delicate work of reconstructing bomb damage continues. The structure is incredibly intricate, yet it is also spare.

Just in front of St. Ouen is the old Hotel de Ville, sandblasted and presentable, but still the squat temporal protector of its Norman ecclesiastical neighbor.

Familiarity makes us fail to see it, but this is really a photo of a sea of cars. They fill Rouen’s central square, named for de Gaulle or not.

The Hotel de Ville’s modern counterpart – these days they are simply called administrative centers – is across the river. It is a handsome enough building, a little reminiscent of United Nations headquarters on the East River. It is not, unfortunately, reminiscent of Rouen.

The estrangement is stylistic, of course. The long glass facade could be anywhere in the world. The new hub’s separation from the main city is also physical. The Administrative Center is a long way around from the Hotel de Ville. Over the years, the Administrative Center will likely become the new city center, and the old heart of the city an “Old Quarter,” animated chiefly by tourists and school groups.

A new Rouen is rising on the rim of hills that surrounds the old. The views are absolutely magnificent, and the new buildings are skillfully oriented to make the most of them.

Rouen has more than its share of “urbanists” and master plans, and they may serve to keep the city from flowing indiscriminately outward, ravaging its own distinction.

It is also easy, it must be said, to become precious in bemoaning the loss of the old. Anybody but a very rich or a very poor man, moving to Rouen, would move to an apartment in the hills. Central heating, efficient plumbing, windows that fit, a parking place – all these are things people nowadays quite properly demand. They are hard things to provide in a very old city.

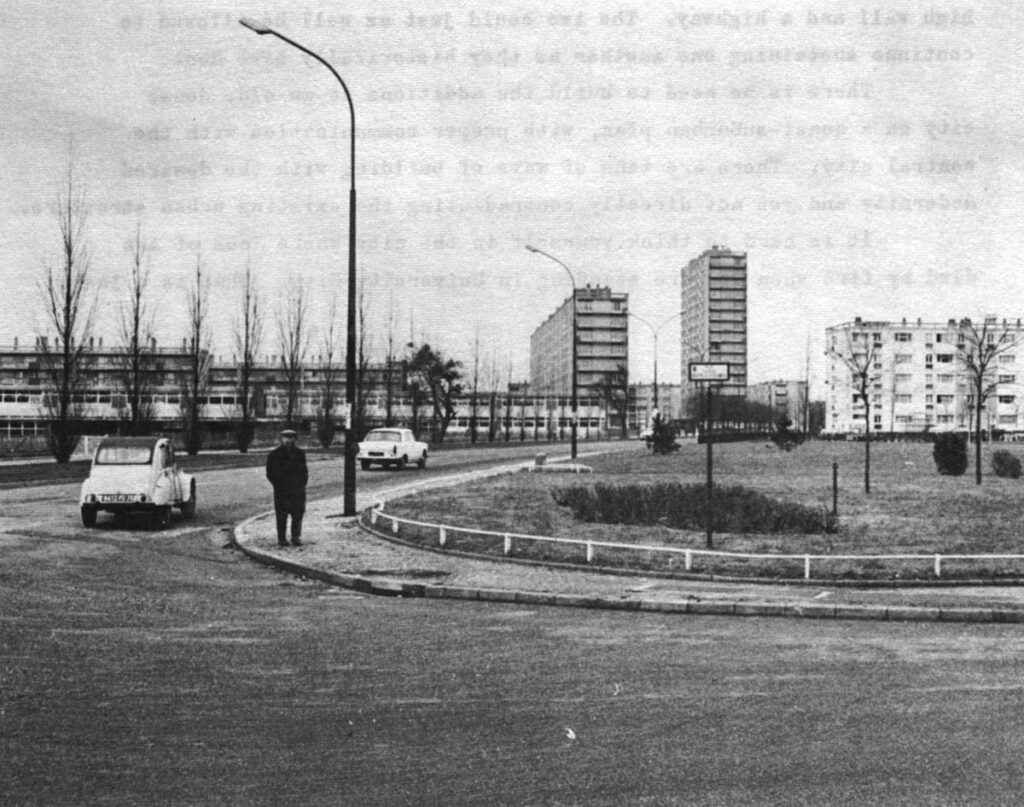

To the right is University City, at the very top of the hills behind Rouen. It has the university proper, 10,000 students, and so far also 3400 apartments not directly connected with the university.

It is open and airy, well-designed and modern.

It could be any-place in France, or for that matter in the suburbs of Washington, DC. An address here is still Rouen, but it is another place entirely. Bus service is infrequent, so dozens of students line the roadside, hitchhiking back to the real city.

Just as the new has a convenience that is undeniably attractive, so has the old a style. The two would seem to combine well, with the old city providing what the new cannot afford, and vice versa.

But the barriers between the two are made greater, not diminished. There are walls beside the river as well as signs saying ‘keep out.’ It is simply too far to walk from University City to downtown, and with bus service lousy they are further apart even than they appear.

The new is being built on a spacious “city beautiful” plan, which is a replacement for old cities, not an addition to them. Twisting busy alleys and wide acres of lawn are not good neighbors.

Old Rouen will continue, on inertia and because it has such style and attractiveness, and because it has so many “historically important monuments” that are being protected and preserved. Because it is set up in contradistinction to the expanding city instead of being an integrated nucleus for it, the old will likely go on becoming less important to the life of the city as a whole.

Medieval cities are not, obviously, the only places facing these problems of change. The analogy to a New England city is easily seen. Georgetown comes to mind as an old quarter given a new life. Georgetown has the money to make all sorts of difficult things look easy. In downtown Manhattan, the old has simply been swallowed by the new, again by the power of money.

The successful modification of an old city is a particularly difficult problem. For every attractive apartment block next to a Palais de Justice, there is at least one wall along the Seine and several pretty squares choked with cars.

Nor is adaptation only of esthetic interest. It is when a city has failed to adapt for long enough that it either ceases to be a city (Fall River, MA, was once the largest spinning city in the world) or that the currently topical American problems of “blight” and “center city decay” happen.

An old sector that ceases to be useful and is isolated (even though central, perhaps) is either a sort of museum, as may well happen in Rouen, or trouble, as with so many downtowns across America.

Some of the problems are perhaps insuperable. Real poverty, racial hatred, or extreme decrepitude of structures that no one yet knows how to solve.

But some problems could be solved as easily as not. There is no need to divide a port from the city that grew up around it by a high wall and a highway. The two could just as well be allowed to continue sustaining one another as they historically have done.

There is no need to build the additions to an old, dense city on a quasi-suburban plan, with proper communication with the central city,. There are tens of ways of building with the desired modernity and yet not directly contradicting the existing urban structure.

It is hard to think yourself in the city where Joan of Are died by fire when you are standing in University City. That is a loss.

Photos-AB

Received in New York on January 5, 1970.

©1970 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.