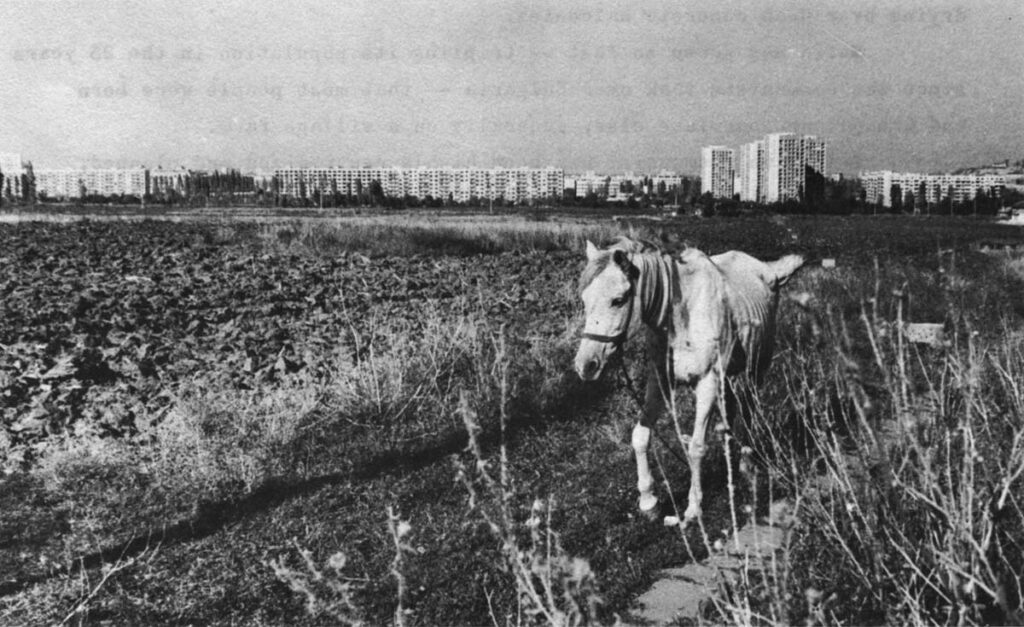

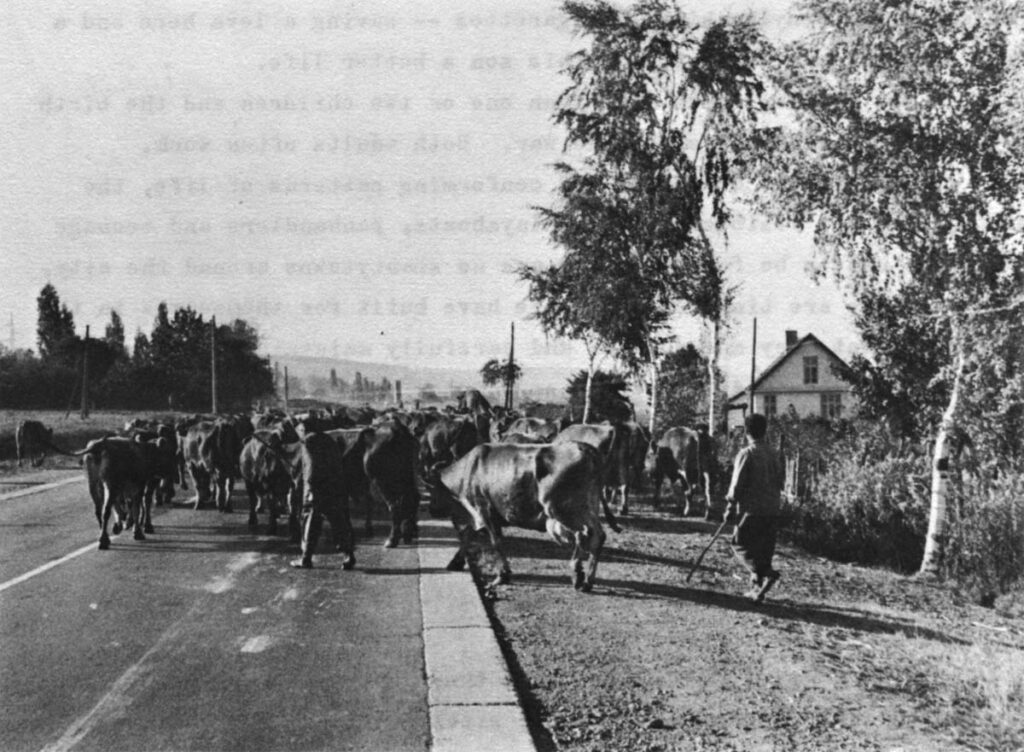

Sofia – Sofia is almost a metropolis and almost a village. Turkeys scrabble in the unpaved street of a new 10-story apartment house. A herd of cows regularly stops later afternoon traffic on the beltway.

It is a European capital city of almost a million residents, but Sofia remains oddly close to the soil. For instance, each new apartment – and practically all of Sofia is new apartments – must by law have a room in the basement called the winter room.

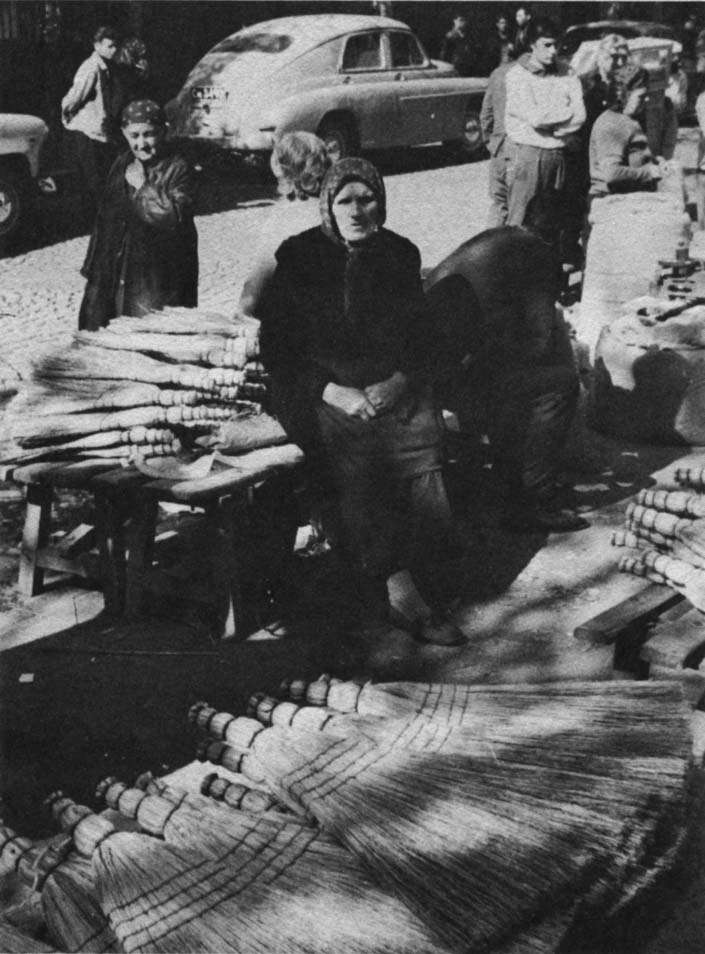

In the winter room bureaucrats and factory workers put down each autumn the winter’s supply of pickled tomatoes and cucumbers. On a Sunday afternoon the streets are full of families bringing home nuts and wine and apples from “the village.” Strings of red peppers hung drying over drab concrete balconies.

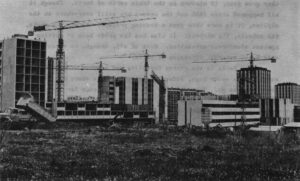

Sofia has grown so fast – tripling its population in the 25 years since the communists took over Bulgaria – that most people were born and brought up someplace else, generally on a village farm.

Bulgarian communism has been highly centralized and planned, orthodox, and all-controlling. Bulgaria has been Russia’s most faithful, unprotesting ally. Dissent has been squashed in its earliest stages.

The radical change going on here is not toward political and artistic freedom. What is new in people’s lives is urbanization. When Bulgaria became an independent country in 1878 Sofia had 20,000 citizens. There are now apartment complexes here that big.

The apartments are tiny, overcrowded, usually shared. But the forces building Sofia are powerful: the pull toward the place where all decisions are made, the push away from a mud-floored village house.

Sofia so far has resisted attempts at limiting growth. People come crowding in.

Sofia makes no striking first impression. The main square, Lenin Place (which, incidentally, has no traffic lights and needs none) is surrounded by, depressing Soviet-monolithic buildings housing the party headquarters, the main department store, the biggest hotel.

There are a few dozen blocks of old city, the commercial core. Then, out any road from the city’s center, are hundreds on hundreds of acres of post-war apartments. Some are terribly drab, some are visibly shoddy. The newest ones are quite handsome.

The streets are convenient, planned in advance of the buildings. Every-where they are lined with young trees. Their green softens the new hardness of the concrete facades.

Every street us swept and washed daily with an almost fanatic pride.

Stores, both downtown and in each apartment cluster, have large stocks of a limited range of goods. Prices are high. The stores are jammed with shoppers and browsers.

There are lines for bread, vegetables and opera tickets, but it seems to be because of the way the system is set up, not because of shortages. After a while, everyone is served.

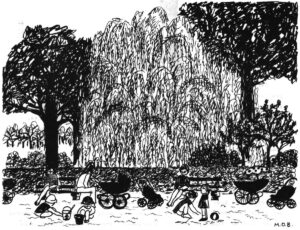

From early morning until about 10 in the evening the sidewalks, parks and restaurants are crowded with people talking, reading, on their way. Young girls wear mini-skirts (called by the French name mini-jupes) and old women long peasant dresses and kerchiefs. Men often wear a business suit but no necktie.

One reason people are on the streets is that the apartments are so crowded. The crunch of becoming a city is happening behind the walls.

According to the census, there are 1.7 people to every room in Bulgaria. That’s not quite three times as crowded as Britain or the U.S.

Put another way, each Sofia citizen has 10 square meters of space. That works out to the same space as a large American living room for a family of four to cook, eat, sleep, bathe, study and do everything else that needs to be done at home.

There are virtually no pets in Sofia. There simply is no room.

There are 60,000 Sofia families who have made a down payment on a cooperative apartment of their own and are waiting their turn. The city builds 9000 apartments a year in all, including those for high priority workers. The wait may be quite a few years.

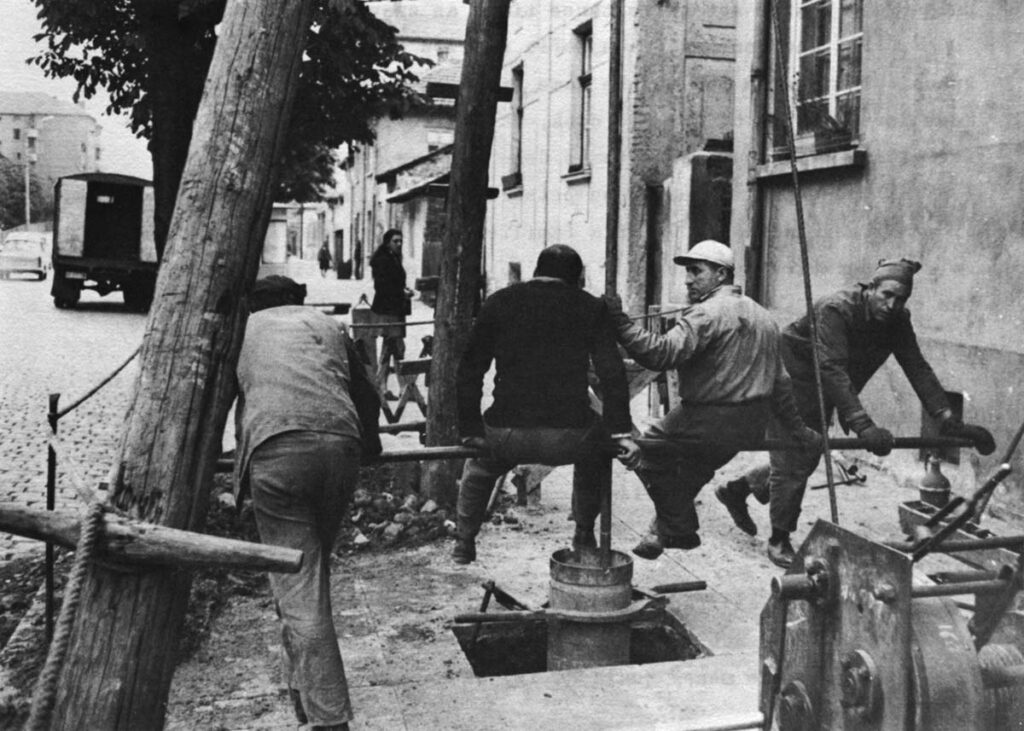

Central planning control has its obvious advantages. It can dictate where and how apartment buildings will be built. The unpaved street where the turkeys strut will be paved. For a city that is one huge construction site, Sofia is tidy. The mayor of Sofia is a young architect, Georgi Shoilov, which may be one reason new buildings are handsomer.

But what all the two-stage master plans cannot do is build enough housing – not now, not in five years.

A lot more money would do it, but resources are spread thin when a country moves a quarter of its population from the farm to the city in 25 years (Bulgaria’s population of somewhat more than 8 million is now 50-50 urban-rural).

Bulgaria is trying to build heavy industry where there was none and where some important resources are lacking. Roads are being built where there were cart tracks. Tourism is now a major industry in a country that practically nobody visited a decade ago.

Economic development is a delicate balancing of urgencies. Housing doesn’t do anybody much good except the people who live in it. Rents, as a matter of policy, are low. An apartment building is a public expense. The same investment in a hotel will return tourist dollars.

Technical innovation is one answer, according to an engineer named Kourdalanov, chief of the department of technical science and progress at the Ministry of Construction.

The insatiable demand for housing will continue as long as Kourdalanov can anticipate. The more they can mechanize, the more efficiently they can build, the more units they can build.

Prefabrication is one answer. Half of Sofia buildings are now prefab; in 1975 it will be 70 per cent. Prefabs are cheap. But above all, Kourdalanov points out, they are quick.

When a new factory goes up and people must ride all the way across town on packed trolleys, housing becomes a pressing economic need as well as a social one, and quickness is important. Sofia winters are cold, and a prefab can be closed in against the elements so finishing work can go on.

But machines and people skilled to run them are often not available in Bulgaria. When unskilled labor is idle, it is put to work on the older, more familiar construction methods.

The disadvantages of prefabs are recognized, too. They offer little scope for imagination, Kourdalanov says, and not enough isolation. The meaning of “not enough isolation” became clear in a cartoon in the weekly newspaper “Observer:”

Patient – “I keep hearing voices, doctor.”

Doctor – “That’s no cause for worry. You live in a prefab.”

Money deposited by families waiting apartments is also used as the capital for current construction, in much the same way as an American savings and loan society.

The buildings will be cooperatives, built by the state construction monopoly, but owned by the tenants. The Bulgarians are proud that this pattern of cooperative ownership, which accounts for half of Sofia’s construction, has been copied by the Soviet Union.

An emphasis on frugality and saving for the future is very much a part of Sofia. Bringing in vegetables from the village, keeping a few chickens, denying himself cigarettes – saving a leva here and a leva there, a man hopes to give his son a better life.

Few families have more than one or two children and the birth rate has been dropping since the war. Both adults often work.

For all the demanding and conforming patterns of life, the misfits are not visible. Drunks, layabouts, panhandlers and teenage gangs are not to be found. There are no shantytowns around the city.

There are tiny houses people have built for themselves in the outskirts, but they are coveted and carefully maintained. They offer a little more space and a little more privacy than a family could expect in a shared apartment. As I walked past one I heard a string trio rehearsing.

Every Sunday there is an exodus from the cramping city to Mt. Vitosha, a great wooded mountain a half-hour’s bus ride from downtown. On a beautiful day, 150,000 Sofians will be hiking, picnicking, or skiing on the mountain.

Others go to the garden plots they rent for practically nothing (2 leva or $1 a year) on the sites of future apartment buildings.

One man talked of the need to plant his raspberries well, so his neighbors would not say he had forgotten the village ways and become too citified.

Sofia officials are acutely aware of the problems of overcrowding, and have announced they will limit the city’s growth. Of course no more people will come, Engineer Kourdalanov said, because we will not let them.

They must register with the police, and they cannot do that without a proper place to live, he said. But it seems to a westerner that the city is too much the center of the country, too strong a magnet, for growth to stop all of a sudden. Moscow has had similar problems.

Officials talk about parking problems and requiring garages in new buildings, and about a subway, and the other curses of urban affluence. But they are for the future. Sofia lacks the abundance, the variety, the accumulation of generations, that mark older cities.

Sofia is new and plain and functional. It has nothing not urgently necessary, except the beautiful young trees and clean streets.

Western movies have long lines and play to packed houses from early morning to late evening. There is a crowd of from 25 to 50 people examining the display of space pictures in the window of the downtown American Embassy all day.

A Buick belonging to an American tourist draws a crowd of youthful examiners wherever it is parked. Cars are only beginning to be common. It is the hard riding Soviet Volga that is most frequently seen.

Not everything is earnest and proper, even toward most trusted allies. Entering a hotel, an inquiry about whether there is anybody in the dining room draws the response, “Oh, no, just some Russians.”

But variety and relief from a hard and regimented city is more often from the past, from the village, than from the plush future.

A man and his boy driving up an empty boulevard in their rubber-tired wagon behind their fine brown horse look proud and satisfied.

Sofia’s citizens are being asked to save for the steel mills, save for the needed tourist dollars, put off a new apartment or a car.

The village is still close enough, however, so it isn’t some idealized memory. Even a cramped city usually seems better. As a Balkan tourist guide put it:

“When I went to language school in 1948 I was wearing shoes my mother made from the skin of our pig. Now (proudly thrusting forward his lapels) I have a suit and tie.”

Photos-AB

Received in New York on November 10, 1969

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.