Paris, Feb. 8, 1970

When Georges Eugene Haussmann was put in charge of Paris, he planted his feet, took hold of the city, and shook it. He kept up this approach to running the city for 17 years. When he was through, there was little of Paris that hadn’t been rebuilt, or torn down, or both.

Just a century has passed since Haussmann was fired. Paris is still his. Not everything, to be sure. The Metro and the Eiffel Tower are since his day, and perhaps a few other things. But Champs Elysees, Etoile, Opera, Boulevard St. Michel – all the famous boulevards of Paris are Haussmann’s. The sewers are his. The water is, too. (Yes, the water is safe to drink. It also tastes all right.)

The Louvre was finally finished by Haussmann. The Bois de Boulogne was built by Haussmann. Longchamps is Haussmann’s work. So is almost every other Paris park. Even now, more Paris houses were built by Haussmann than by anybody else. Les Halles, for a thousand years the central market of Paris, was entirely rebuilt by Haussmann.

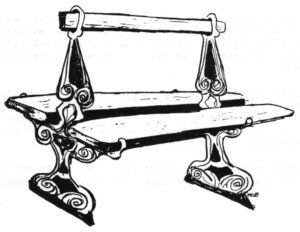

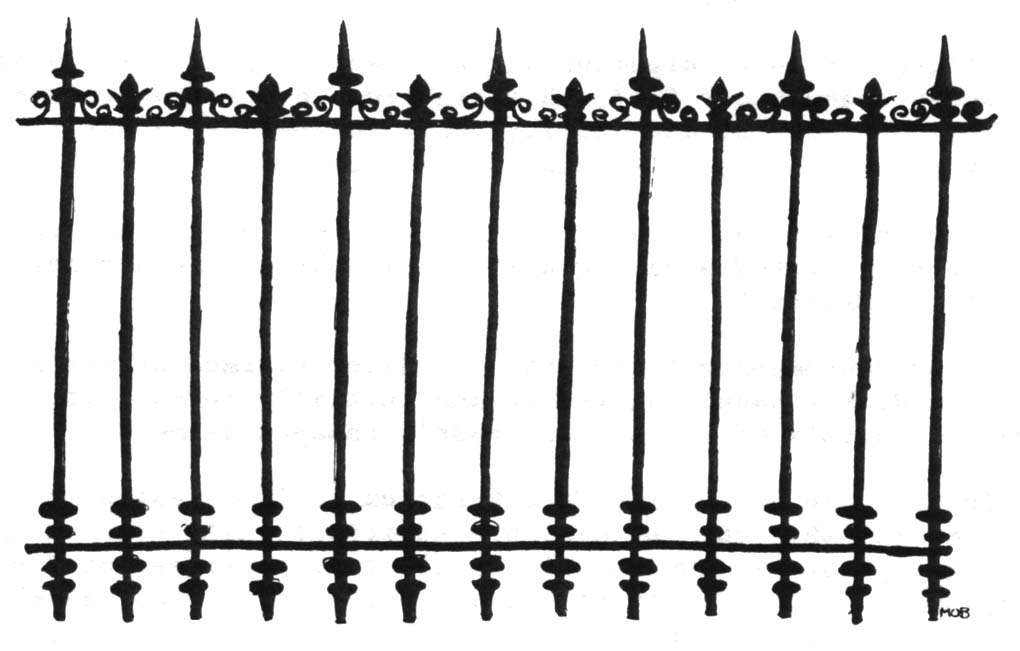

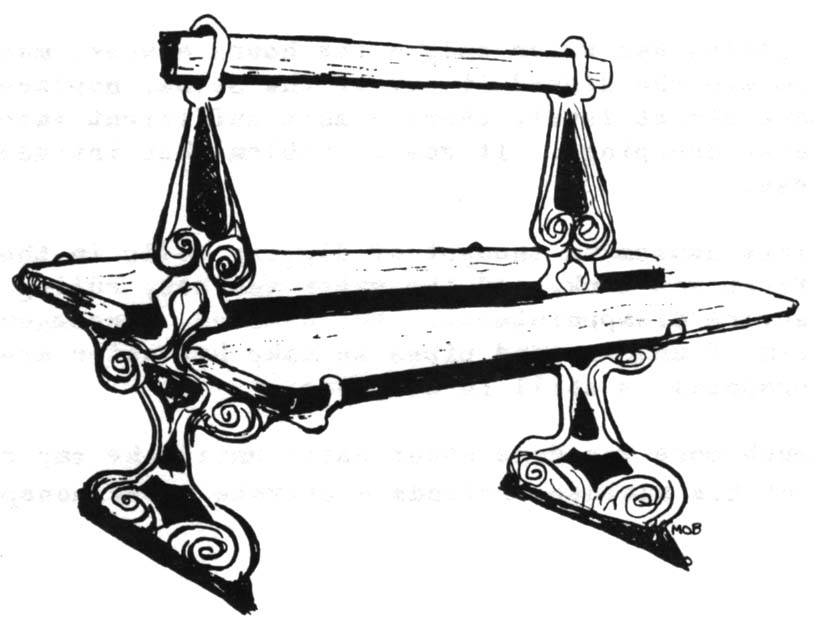

Paris still looks the way Haussmann wanted it to look. The trees are his. The sidewalk benches are his. It was he who decided urinoirs were a civilized thing to have around a city’s streets. The lamp posts are his. Row on row of similar facades – six-story apartment buildings, shuttered, ornamented in iron – show how Haussmann thought a city should look. That is how Paris looks, although change is beginning.

Who was this fellow, known always as Baron Haussmann? (The title was adopted from one of his maternal ancestors.) From 1853 to 1870, he was Prefect of the Seine. The position itself gave him the powers of a sort of super mayor. He was also Emperor Napoleon III’s collaborator and delegate. He had power to do virtually anything, though there was no lack of resistance.

What Napoleon III wanted was to make Paris a great city, without raising taxes. He told Haussmann to do it, and Haussmann did.

Of course, to speak of Haussmann alone is to slight hundreds of others, including the emperor, who himself drew plans and urged forward the embellishment of the city. Haussmann worked almost entirely through subordinates. It was Haussmann, however, who moved ahead with the emperor’s plans after other prefects had stuttered for four years, accomplishing little. It was Haussmann who took credit and blame for everything during his administration.

What Haussmann brought about is a remarkably thorough urban renewal for Paris. This piece will describe some of what was done and how it was done. A second piece will be about the effect a hundred years have had on the renewal work itself, and the city that was so shaped by the renewal.

In other words, the question is this: How do you bring off a real urban renewal project, and how does it stand up over the years?

Paris is an easy city for travel posters, or movie makers, or anyone else who needs to provide immediate visual identification of place. Paris looks like itself, not someplace else.

Much of this is due to Adolph Alphand, one of Baron Haussmann’s lieutenants, and a road engineer by training. Asked to design a street, he designed everything on it – kiosks, benches, railings, lamps, sidewalk gratings, placement of trees – as well as the street and the sidewalks.

It is the same sort of care big American firms take in designing logotypes and other institutional identifying signs.

Alphand and Haussmann did it as a matter of esthetics. They cared about the look of a sidewalk, just as they cared about the view up a boulevard.

1842 Louis Napoleon is in exile, his aspirations to rule France clearly ridiculous to those in power. Haussmann is a provincial bureaucrat, sub-prefect of a district called Blaye, near Bordeaux. At 33 he has been in the Prefectoral Corps for 12 years, and is becoming both skilled and experienced. He is not, however, particularly noteworthy, his explicit ambitions notwithstanding.

A man named Jacques Séraphin Lanquetin is a member of the Paris City Council. This is how he saw the city:

“To my colleagues on the Paris City Council, Greetings:

“It is no longer a mere need, it is now a necessity of the highest urgency that we bring to bear every municipal effort to remedy traffic congestion in most of the streets of central Paris. It is a need for the future as well, because the wealthy population flees this congestion and builds new neighborhoods, one after the other, on the outskirts of Paris.

“The rich in turn are followed by, the fancy businesses, then by other commerce that always tends to seek proximity to the wealthy….”

He goes on at some considerable length to accuse city government of inaction in the face of this crisis:

“We will be caught up in incalculable city expense for the needs of the new neighborhoods, while leaving without financial resource and without value a large number of houses and rich establishments and public facilities in the abandoned neighborhoods.”

Better streets are the answer, he feels, allowing communication between isolated neighborhoods, and thus more equal preservation of value throughout the city. This isolation of neighborhoods one from another is confirmed by other writers. ( Indeed it is a problem in present-day American cities, where the richest and poorest neighborhoods frequently abut without communication.)

Nothing has been done, Lanquetin says, because:

“It is believed, undoubtedly, that what could be done would not be effective, and that what should be done would involve such exorbitant expenditures that the state of city finances wouldn’t allow it. So we say let’s go on running things from day to day. It is impossible to disguise the fact that this is the distinctive character of the present city administration.”

Streets weren’t the only problem that unmistakably demanded attention. Paris, like other European cities, was seriously hit by cholera epidemics in the 1830s and 40s, for the first time.

Without following the complicated theories of contagion then held, they led to the conclusion that cleanliness produced health, and Paris was filthy. Drinking water often had to be sieved. Ordure was simply piled in the street for sporadic collection.

Paris in 1850 had just reached a million population, and was to nearly double again in the next 20 years. Many, if not most, people were grossly ill-housed. Ever more people were cramped into buildings that in turn were cramped within the city’s walls. The overspill beyond the fortifications had begun in earnest, creating suburban islands entirely without streets or sanitation.

Clearly, something had to be done about Paris. She had undergone a half century of revolution and turmoil without much care, and it was showing.

There was even, to complete the analogy with a modern American city that keeps coming to mind, a crime problem. Good citizens feared the streets where brigands and dens of thieves held sway. Curiously enough, crime was the responsibility of a separate city government. Haussmann’s full employment, professionalization of the police force, and introduction of police beats (an innovation) brought the problem under control.

The good M. Lanquetin had a program:

“Improve, beautify, cleanup, regenerate, within the limits of our powers. That is my program, and nothing could be more harmful to it than the utopians who exaggerate to the point where they can see nothing but destruction and reconstruction of all Paris.”

In 1852, Napoleon III, finding himself with a Prefect of the Seine of just this cleanup, fix-up, sort, ordered his minister of interior, the Comte de Persigny, to find him a man who could really get moving on making Paris a great city.

Haussmann was among five candidates interviewed. He remembered the occasion as a meeting of soul mates, communicating with perfect frankness and understanding from the first. Persigny remembered it this way:

“I had before me one of the most extraordinary characters of our times. Big, strong, vigorous, energetic, and at the same time sly, cunning and resourceful; an audacious man who didn’t hesitate to show himself openly for what he was. With visible relish he laid before me the events of his administrative career, sparing me nothing; he would have talked for six hours, so long as it was on his favorite subject, himself.

“As for me, while this fascinating personality displayed itself for me with a sort of brutal cynicism, I could hardly contain my satisfaction. ‘To fight,’ I said to myself, ‘against the ideas and prejudices of a school of economics, against tricky, skeptical, unscrupulous men from stock exchanges and lawyers’ offices, here is just the man.'”

“Where an able, highminded gentleman – upright and noble – would undoubtedly fail, this vigorous, oversized athlete, full of audacity and ability, able to meet expedient with expedient, ambush with ambush, will certainly succeed.”

“I enjoyed the prospect of throwing this jungle cat in with the pack of foxes baying against all the generous plans of the Empire.”

Baron Haussmann got the job. He later claimed he was not only surprised, but hadn’t wanted it and initially refused it. The queer public modesty of politicians hasn’t changed so much.

In any case he arrived from Bordeaux in 1853 convinced the best man had got the job. He made his political calls (including telling the empress his own and his wife’s full genealogy on first meeting), put on a brief show of his authority before the assembled city employees, then started studying the budget.

His way of working is of some interest:

He had the emperor’s ear, seeing him often daily, always weekly, throughout the 17 years. They would talk, often for hours, the emperor suggesting, Haussmann modifying toward feasibility. He is said to have been as fascinating on the subject of sewers, or any other aspect of rebuilding Paris, as on himself. His small talk, however, often bored his dinner partners.

He made alliances, particularly with the leaders of the City Council, that he cultivated most carefully indeed.

He had a few valued subordinates. They were experts and innovators, as consumed with aqueduct design or park path layouts as Haussmann was with Paris as a whole.

It was from these colleagues that Haussmann drew many of his ideas, often later presenting them as his own. He was unwilling to accept expert advice on faith, and wanted to be taught the ins and outs of the problem. In return he cherished and protected these men, even when they caused him public embarrassment.

People outside these categories – unuseful people – were usually treated politely, but were without interest. He would suavely ignore legislative inquiries he thought silly, discomfiting powerful men. Subordinates he thought unworthy were given short shrift. Of a M. Husson, a department head in 1853, Haussmann later wrote that he was capable, but that “he instinctively saw things through the wrong end of the spyglass.” M. Husson soon enough departed.

Although Haussmann delegated practically everything, he continued throughout his career to read, nightly, a draft of every document that was to bear his name. He would comment, in the margins, sometimes apparently as much to show he was still reading as to make a substantive change. There was no aspect of the city’s business in which his control was not felt.

Running the city was approached as a manageable job. Perhaps partly because of that approach, it was a manageable job.

A brief sketch of the ‘water saga,’ a continuing tale of heroes and villains that ran through the whole Haussmann administration, may be illustrative of how he ran the city. It was clear to Haussmann (though probably not to the emperor, who thought in grander terms than buried pipes) that there was not nearly enough water, and its quality was atrocious.

Some places had water only a few hours a week, many had to buy water from men who dipped it out of the Seine, noplace was water available above street level, there wasn’t sufficient water to flush away horse droppings. It was a problem that intruded on the daily awareness.

At first Haussmann thought of digging wells in the city, at Passy. The first was sunk, and the water was hot, ruling it out for drinking, a severe disappointment. Not daunted, Haussmann proposed a second system of underground pipes to take hot water around the city. This proposal is still in abeyance.

Not much more was done about water until the emperor proposed to give some of his business friends a private water monopoly (as was done in London at this time, to the city’s lasting detriment) to sell the water of the Seine.

Haussmann rose to the occasion, said not only should it not be a private system, it should not be Seine water – dirty, warm, insufficient. He had a plan, he said, for tapping distant springs and bringing their waters to Paris, as had the Romans.

The emperor, never reluctant to be compared to the Romans, said fine, go ahead.

Only then did Haussmann go out and hire a man he knew who was good at finding water and building water systems, Eugene Belgrand.

Haussmann and Belgrand worked up a plan, then got into a six-year fight with the economizers over the huge size of the expenditure, and with the Seine water advocates who said it was silly to go elsewhere with a river running through the city.

It was only as the project neared construction that Belgrand informed Haussmann there had been an error, there wasn’t enough water in those springs, and a second aqueduct in a different place would be needed. Haussmann shifted without missing a beat to the new plan, which was approved, built, and did indeed provide excellent water for the capital. Augmented, it still does. If work had gone ahead quickly, without the extensive harassment of various opponents, a hugely costly error would have been committed.

Fifteen years later (1872), by which time they were all retired for one reason and another, Belgrand mentioned his error in an article. “But the uninterrupted droughts with which we have been afflicted since 1857 quickly showed me wrong. It was necessary to abandon the operation.” That is all he wrote, going on to other matters.

Haussmann was astounded that it should be mentioned so baldly. Of Belgrand he writes: “He seems not to have been bothered at all by the eventual consequences for my administration.”

An aqueduct more than a hundred miles long, on which the whole prestige of the city administration had been staked in a years-long fight, came within an ace of being put in the wrong place. Haussmann, the professional, didn’t hesitate to correct the mistake, didn’t recriminate over an honest error. But to mention it – he was aghast.

But then, on reflection:

“Evidently this truly extraordinary engineer was wiser than the administrator. He understood that…(concerning huge errors) one must congratulate one’s self for having escaped, even thanks to outside circumstances.”

Haussmann handled the problem of adequate water for Paris very well, and he wanted to be sure everybody put the credit where it belonged. “It is indeed mine,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I didn’t find it in the emperor’s program for the transformation of Paris, and nobody suggested it to me. It was the fruit of my observations, of my assiduous research as a young bureaucrat and of the meditations of my mature age. It is my own conception.”

Which is a silly thing to say. It takes nothing at all away from his accomplishment to point out that the need for water was obvious and widely recognized. Haussmann’s talent was that he actually got the water flowing in the city, which others for decades had failed to do.

Haussmann liked the power. He liked the good life, too, and turned it to his professional advantage.

His parties in Hotel de Ville, which usually broke up about 10 a.m., were attended by the emperor and everybody else. His Bordeaux cellar was said to be the best in Paris. He was seen, just indiscreetly enough, with his opera singers in a coach in the park. He was a sort of personal embodiment of ‘fun city,’ and his style allowed him to ignore arguments he might well have lost.

His parties in Hotel de Ville, which usually broke up about 10 a.m., were attended by the emperor and everybody else. His Bordeaux cellar was said to be the best in Paris. He was seen, just indiscreetly enough, with his opera singers in a coach in the park. He was a sort of personal embodiment of ‘fun city,’ and his style allowed him to ignore arguments he might well have lost.

He was not, however, only a showboat. Education, for example, was not one of his interests. He was never involved in a big fight about it. Nevertheless, education expenditures were six times greater when he left than when he came, and the city underwent huge population growth without the school troubles that almost always go with it.

The same could be said of welfare services, or maintenance of the price of bread, or routine street cleaning.

Everything worked a little better, or seemed to, under the Baron. That is probably one reason the citizens put up with him tearing up their city with money he didn’t have for so long as they did.

Describing Haussmann’s major undertakings briefly is impossible. Listing them in particular takes a book.

To give an idea of the magnitude of the work, at one point in the 1860s, one in five workers was employed on the renewal projects. By conservative accounting, Haussmann spent, in 17 years, for special projects alone, 44 times the whole city budget when he took over. Tax rates were not increased.

Streets were lowered and raised tens of feet as a matter of commonplace. The Tour St. Jacques de la Boucherie, a massive stone affair several stories high, was five or six meters too high for the newly-built Rue de Rivoli. Haussmann had it suspended from a wood scaffolding while a new bottom was built under it. After that success, well publicized, Paris was convinced their new prefect could do anything.

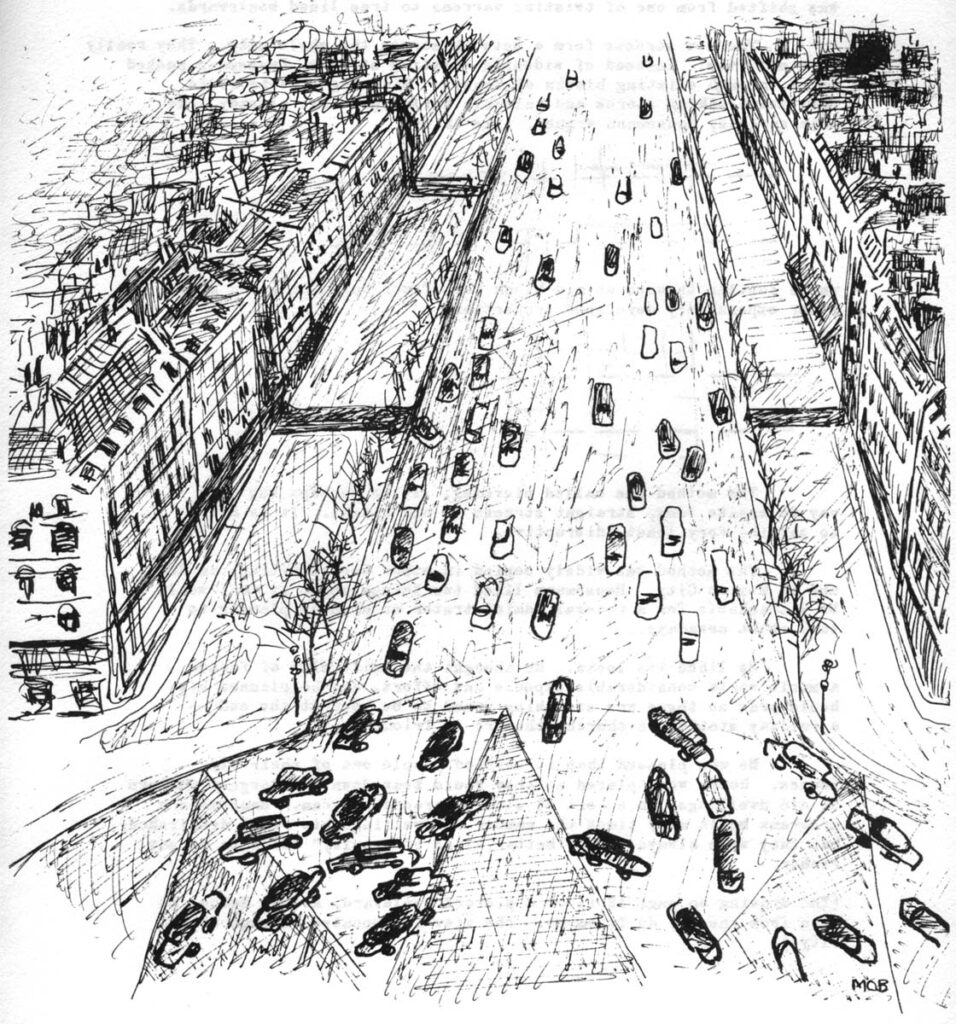

The streets were the biggest work. Virtually every straight, wide street in Paris was suggested by Napoleon III and built by Haussmann. They give the city its “grand cross,” an axis of north-south and east-west streets. They opened the railway stations to each other and to the center of the city. The basic pattern of Paris streets was shifted from one of twisting warrens to tree lined boulevards.

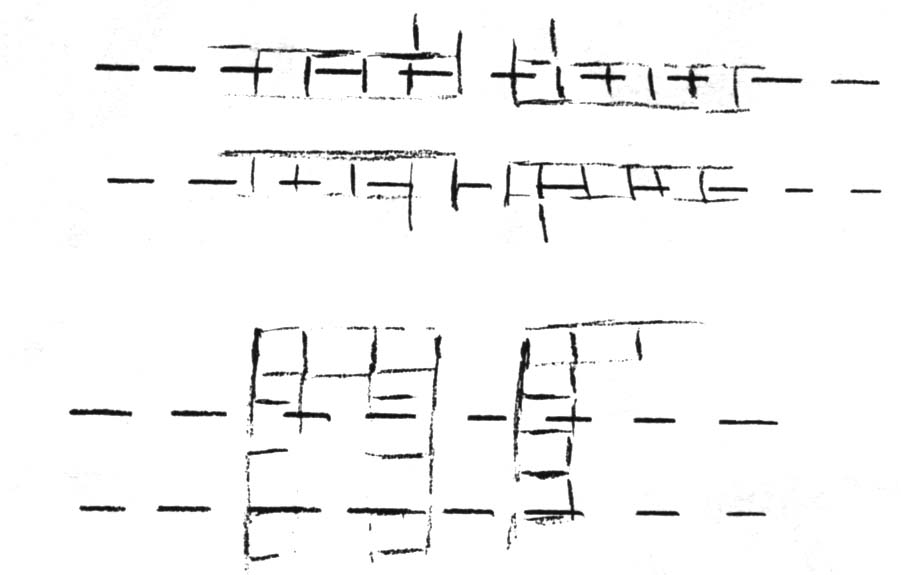

Top – The new streets form a network across the whole city. They really were new, too. Instead of widening existing streets, Haussmann pushed right through existing blocks of houses. Widening streets would have meant taking stores and valuable buildings that already line main streets, Haussmann argued, like this:

Bottom – While cutting through at mid-block took fewer buildings, and many fewer expensively developed properties.

The method was called piercing. It is perhaps the only way to create long, straight streets in old cities. It is also, to say the very least, disruptive.

The method was widely copied in other French cities, in Rome, and in Mexico City. Haussmann liked two things about it that would be unthinkable for a renewal administrator or highway planner to talk about nowadays.

He liked its looks. He thought the uniformity of facade a merit worth considerable expense and effort, and he planned his boulevards so there was something grand to be seen at the end – a railway station, a church, the Arc de Triomphe.

He was pleased that it shifted people out of their old houses. Roads were placed so they would tear down the largest numbers of old dwellings, in a sort of slum clearance program. Haussmann’s programs built many times the number of dwellings his roads demolished, but they were always for a “better class of people,” which is to say richer.

The drawing is of a pierced boulevard, Avenue Hoche, as seen from the Arc de Triomphe. The view is repeated throughout the city.)

Compensation was paid, of course, for demolished houses. Sometimes it was handsome, usually not. The effect of replacing slum after slum with bourgeois housing was to keep the poor constantly moving, as has been done in many American cities.

Haussmann was not unaware of this, neither was he sympathetic:

“One cannot displace 117,553 families, one cannot dislodge 350,000 people and the industrial and commercial establishments they use, without a general disruption of which the masses tire easily, since they cannot appreciate its indispensability, especially when it goes on for 17 years.”

(350,000 people is more than a third of Paris’s population at the time of Haussmann’s arrival.)

Any one of these other Haussmann era projects would mark a lesser administration as active and progressive:

The city boundaries were moved out to include the fast-growing communities outside the defensive (and tax collecting) walls. There was objection from the suburbanites who would now have to pay more tax, and from the city dwellers who would have to pay for providing proper facilities to ill-equipped new developments. These suburbs are now the 13th-20th Arrondissements, and obviously part of Paris.

New and much expanded facilities were built for the city’s markets at Les Halles and abattoirs at La Villette. What it amounted to was a modernization and further entrenchment of old economic patterns. Successive administrations have for a century had cause to wish something else had been done.

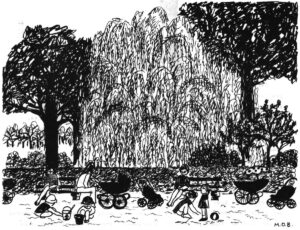

Two big parks were developed, the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. More than a dozen smaller parks were built. Haussmann felt this to be one of the most important accomplishments of his administration. With the tree and bench lined boulevards, the parks changed Paris from a constricted, dark city to an open, green one.

The famous sewers of Paris were built. You can still ride through them on a boat, although even chauvinistic guidebooks now recognize it to be a little tacky. It was not always so. Monarchs made the underground voyage from Concorde to Madeleine. The sewers also removed the universally noted stink of Paris.

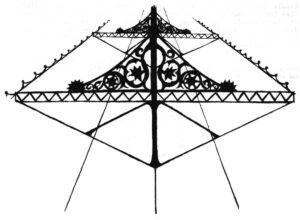

It was characteristic of all Haussmann’s work that when he was through, something looked, by his lights, right. The street was wide enough, not a compromise, trees were planted, the building fronts were uniform. With the benches, gratings around tree bottoms, railings, even the roof supports for a small shelter (opposite page)–everything had been designed as a piece. It all looked the way an efficient administrator would want it to look, if not necessarily the way an architect or artist would choose.

Also, the changes were made throughout the city, not in islands here and there.

For each project it seemed someone besides Haussmann was the kingpin. The interest and continuing support of the emperor were clearly indispensable. Haussmann was not an architect, nor was he an engineer. But he ran the whole operation.

It is the scale and thoroughness of the renewal that make it unique. Really, very little new was done. None of the techniques or ideas was less than decades old.

Subways, for example, were being built in London in Haussmann’s time. He knew of electricity and scoffed (he said it would be appreciated only by oculists).

It was a renewal that brought together all the accepted and proven ways of doing things, and put them into practice, all at once. The result was change – urban renewal – on a scale seldom seen before or since.

There is a last element of this story that needs to be told, at least briefly: how it was paid for.

The previous city administration contended there simply wasn’t enough money to move ahead as the emperor urged. The budget was already stretched to the point prudence allowed.

As Haussmann tells it, he found immediately that the books had been cooked to mask a substantial and continuing surplus.

As Haussmann tells it, he found immediately that the books had been cooked to mask a substantial and continuing surplus.

Prudence, that eternal friend of municipal bankers, might have allowed him to spend most of this on new projects. He used all of it instead to pay the interest on a loan, which was then an audacious thing to do.

This, with a big national grant, paid for the first burst of activity. It would now be considered a most ordinary sort of financing.

For the second big group of work, a wrinkle was added. It basically took advantage of the increased value brought about by the city’s work. Not content to have tax valuations go up and gain revenues with a lag of several years, the city was able to borrow in anticipation of this increase in value.

The city also bought and cleared wider paths for roads that it strictly needed. It bought at mid-block slum prices, and sold to developers at new boulevard prices, using the difference to pay for the next project.

This financing is a little less conventional, but not so very odd when a project is widely known to have the emperor’s backing. It was done within limits set by the national government, and with a much smaller national subvention.

The third wrinkle was for the city to lend its backing for bonds issued by private firms undertaking major segments of the reconstruction. This was outside the city borrowing limits, because it was private, not city, borrowing, at least in name. It is clear the bonds would not have been sold without city backing, however. This paid for the third group of work, by which time the provincial members of the assembly were convinced far too much had already been spent on Paris, and refused to spend more.

Nobody ever made a specific charge of corruption stick against Haussmann or his colleagues, a remarkable record after 17 years of closely, even maliciously, scrutinized wheeling and dealing.

But the irregularity of the third financing method was the handle needed to pull Haussmann down, nevertheless. A tract called “Les Comptes Fantastiques de Baron Haussmann” was widely circulated. It really didn’t need any more than its title to focus the many discontents of Haussmann’s enemies. (Ironically, the tract’s author, Jules Ferry, later had a small segment of one of the Haussmann Boulevards named after him.)

The emperor, in trouble on every front, acceded to his new ministers who wanted Haussmann’s hide. He refused to resign, and so was fired.

The emperor, in trouble on every front, acceded to his new ministers who wanted Haussmann’s hide. He refused to resign, and so was fired.

(I’ve dispensed with the paraphernalia of citations in this piece, in the hope it can be read as a story, not a research report. I will, however, be happy to send along any references a reader might find useful. AB)

Received in New York on February 16, 1970.

©1970 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Barnes is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Andrew Barnes, The Washington Post, and the Alicia Patterson Fund. Molly Barnes, who made the drawings, is his wife. They live in Paris.