March 7, 1970

It was just a century ago, in 1870, that Baron Georges Eugene Haussmann finished remaking Paris. He didn”t, himself, think the job was done, but he was fired. The imminent downfall of his political protector, Emperor Napoleon III, was one reason for Haussmann”s dismissal. Another was the legion of toes Haussmann had trod on while moving the city around for 17 years. His enemies finally became too numerous.

Haussmann”s burst of innovation had been over for several years anyway, and the odds and ends were tidied up by succeeding city administrations. In fact, that is a great deal of what succeeding city administrations have done – finish up what Haussmann laid out.

Paris, of course, is a glorious city. It seems presumptuous even to say it. Paris is also a fairly efficient city. For most of the years since Haussmann city governments have been able to decide their problems were not too pressing. And yet, there has been about Paris a certain sense that the city used to be even better.

“You find Paris an attractive and engaging city? Well, yes, perhaps,” (the American resident of Paris, seated across the airliner”s aisle from me, concedes with his eyes that I may be young enough for that to explain my lack of discernment) “but you should have seen it 15 years ago. Then it was truly beautiful, but since then….”

For decades Paris has been so, enticing and beguiling the young, who see in their elders” disenchantment the encroachment of senility. Sometimes the young are too polite to mention it.

Unfortunately, the decline of Paris is real. Cities, like their residents, age. Buildings blacken and sag. The fine chef who made a fine restaurant that made a fine neighborhood goes to Brooklyn to live with his daughter who married a man who works in the Navy Yard.

Cities can be terribly clumsy about keeping up with the times. Sometimes they don”t change at all and gradually become irrelevant. The example of our own times is the automobile. Paris, like everyplace else, doesn”t know what to do about automobiles. It is clear the auto is requiring an ever larger proportion of the city”s money and space, reducing population densities and making life less pleasant, while at the same time it becomes more and. more indispensable.

Over decades, if a city fails to solve such problems, it is defeated by them.

There are others. Pollution is a current concern here, as in the U.S. Public health and sanitation were the 19th century urban equivalents. Housing, particularly housing for poor people, is the eternal Paris problem.

How people and goods and ideas move around a city – communication, to use the current, stultifying word – is a constantly recurring challenge to a huge city.

The bus or subway, the telephone, the pneumatic tube – a new development is made, allowing the city to become larger and include more activities without choking on itself. Then, as the innovation becomes a commonplace, its capacity strained, its facilities deteriorating, the sense of things not being quite what they were before returns.

A city is not static. A new solution, a new technique, a vital leader, new money – something pushes forward several notches at once. Then men age. Money falls into the control of institutional bankers. Gains are either lost or their prominence is diminished by advances in surrounding aspects of the city”s life.

Advances and retreats are all jumbled together, a city being as incoherent as it is. Their pattern even seems random, the gains and losses balancing each other like statistical probability.

Sometimes – rarely – a city is concerted. It marshals all its forces at once and is renewed, even recreated. The 17 years that Baron Haussmann ran Paris were such a time. There has been none like it since.

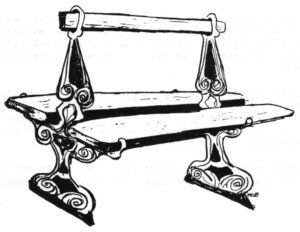

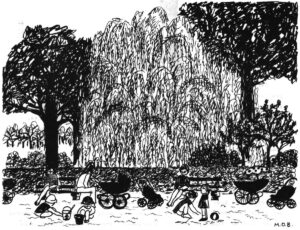

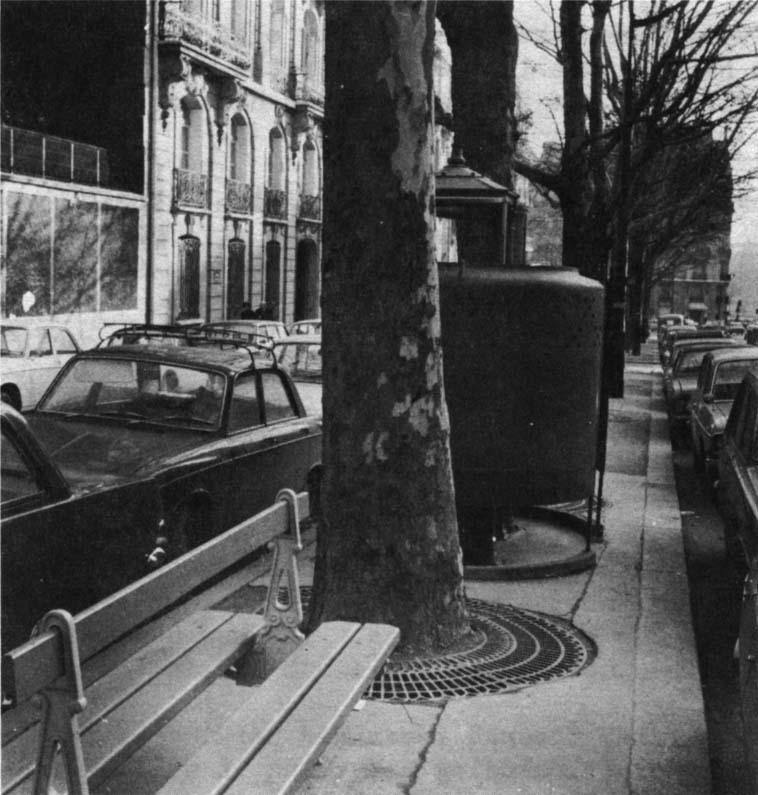

The city”s skeleton of roads and pipes and tracks, and many of its public buildings and monuments, were all fixed in place at once. So, too, was much of the city”s style. The sidewalk cafe, the tree-lined boulevard with its benches for old people and lovers, Sundays in the Bois and a hundred other particularly Parisian activities and ways were determined by what Haussmann did to Paris.

What are the pros and cons of doing so much at once, short circuiting, as it were, the usual diversity and counterbalancing? This is another way of asking whether urban renewal can solve a city”s problems once and for all, and whether that would be a good thing.

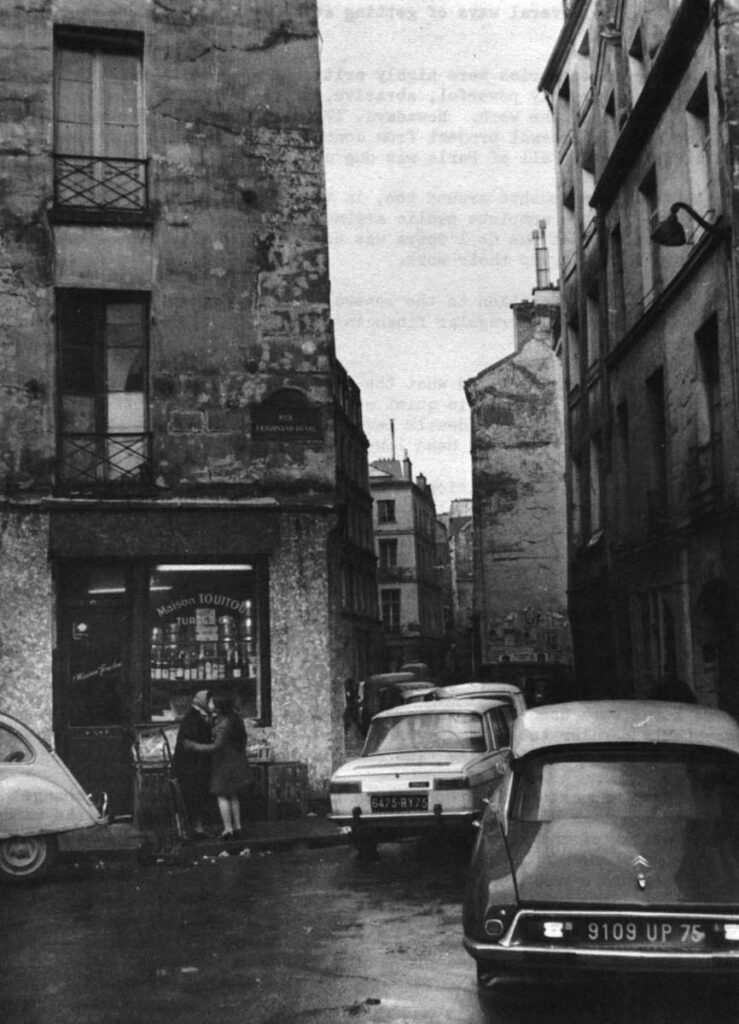

The streets Haussmann left unchanged are still unchanged. Dirty and dilapidated and inefficient, they are also a refuge and a pleasure for many.

here are several ways of getting at an evaluation of Haussmann”s renewal.

His contemporaries were highly critical. Partly it was the man himself – proudly powerful, abrasive, often arrogant. Partly it was the pace of the work. Nowadays, 17 years wouldn”t seem unreasonably long for a small renewal project from conception to completion. In the same time virtually all of Paris was dug up and pushed around.

People were pushed around too, in the name of speed. They didn”t have time to complete public arguments. There was still a solid case being made that Rue de l”Opera was unneeded while the demolition crews were finishing up their work.

There was opposition to the renewal from conservative officials who abhorred debt and irregular financing, both of which were Haussmann mainstays.

Many citizens disliked what the renewal did to their own particular piece of the city. A house in quiet mid-block was suddenly on a boulevard; an entrance at sidewalk level was suddenly meters above it because the whole street had been lowered.

There was much opposition, then, from people who so disliked some particular aspect or result that they never considered the renewal as a whole. Their grievances were well founded, and ignored.

The converse was equally true. Property values went up. Daily trips were speeded. some made money when the city condemned their property (though most, as usual, lost just a little). Parks were built. Many people liked these things, and since taxes were never directly raised, it all had a something-for-nothing quality.

The overall proposal, to “embellish” Paris, to make it “great” (these terms were used again and. again to promote the work) was undoubtedly popular too. Haussmann had his uncritical supporters, as well, writing books with titles like “The Perfect Prefect.”

There was categorical opposition from those who wanted no change at all in what was clearly already a perfect city. “Haussmann the vandal,” or “the Attila of the straight line” were their rallying cries.

They had a point. The work did indeed aim to demolish the old, not simply tinker with it. The esthetic of the unbroken straight line, the monumental vista and the uniform facade did indeed govern.

Docteur Akerlio (nom de plume of a man named Deguerle) writing in 1861 sums up the flavor:

“Where will this furor of demolition stop? When will there be a cease to tearing down solid, well constructed houses, where one could find, at reasonable prices, clean and comfortable apartments? And to replace them with what? With enormous horrors, housing little flats, veritable chicken cages, where one is left to admire the sordid speculation of the proprietor who measures in gold the air and space of his future tenants…”

Place du Palais Royal. Haussmann demolished a notorious slum to build it. Now it is a combination of a parking lot and a through road.

He goes on for tens of pages in this vein. You would think Paris had been paradise, not a decaying, severely overcrowded and congested city of filth, inadequate water and grossly inadequate housing.

Paris needed work when Haussmann came along. Maybe not on such a scale, or with such style, but it was clear things would get much worse if they didn”t get better.

It is a curious twist that the renewal itself was felt to be making Paris somehow less good than it had been, say, 15 years before. And it is so that the dominant voices Haussmann was hearing said go slow, you”re doing too much.

The partisan squabbling about Haussmann was unending. Like Robert Moses, Haussmann seldom produced a neutral response. Ignore him and he might demolish your house while you went out shopping.

And even more powerfully than Robert Moses, Haussmann rode right over his opposition. He didn”t have to pay it any mind, and he didn”t do so.

What of the work itself? In the midst of such furious activity, did Haussmann build the right things in the right ways?

The extent and variety of the work makes it impossible to trace out, even in summary, each of the substantial elements. An example or two is probably enough, anyway.

Take Les Halles. For roughly 900 years the city”s markets had been on the same spot, right in the middle of town. At first it was simply an open place where people came regularly to buy and sell. Later various buildings were built. Under the protection of the kings of France, for it was a royal market, Les Halles was a place of importance in Paris, a source of power and wealth.

The trade was in wheat, leather, meat, cheese, fish and vegetables, mainly. Every grocer and restaurant buyer in Paris went there every day.

The streets were constricted and twisting, and the successful merchants built ever taller and more opulent living quarters over their work and sales rooms. The city”s doubling population meant twice as many cattle, twice as many carts, twice as many boxes of produce, pushing through the same medieval streets.

The scene, by analogy, is familiar to anyone who has tried to move through New York”s garment district. It was difficult to get the job done.

The decision on how to relieve the congestion – enlarge and rebuild the market on the existing site – had been taken by Napoleon I, nearly a half-century before Haussmann arrived in 1853.

Construction, in fact, had begun. A market building had been designed by Baltard, the city”s architect. It was entirely of stone, and had already been nicknamed Fort de la Halle when the Emperor, Napoleon III, first saw it. A man much concerned with modernity and much taken with the open ironwork construction then in vogue for railroad stations, Napoleon III was horrified. He told them to take it down. Since he was emperor, they did.

A grand architectural competition was held., with everybody, including the men who had designed the railroad stations, failing to satisfy the emperor.

Haussmann, meanwhile, had taken the precaution of asking the emperor to sketch what he wanted. To compress a story often told at great length with much recitation of lines like “iron, nothing but iron,” and “the roofs must be umbrellas,” Haussmann had the infamous Baltard draw up formally what the emperor had sketched – a light roof with open ironwork supports, covering a big open space for stalls. Napoleon chose it, of course, and plucked a medal from the chest of a courtier to bestow on the victorious architect, not knowing it was the same Baltard who had designed the fiasco.

Four girls walk back from the ice skating rink installed temporarily in an unused pavilion of Les Halles. City officials are hassling over what to do with the site on a permanent basis.

As Haussmann tells it in his memoirs, he and the emperor were going down stairs after the impromptu decoration ceremony when Haussmann told Napoleon the same man had designed both buildings. “How can it be?” was the astounded question.

“The same architect but a different prefect,” was Haussmann”s conceited answer.

Even he recognized that that perhaps wasn”t the light in which he wanted to be remembered, and starts to explain in the memoirs that he only meant to emphasize the importance of skillful direction and administration and so forth.

Except for an addition, planned from the first, Les Halles continued unchanged to handle all the food for Paris until last year.

It continued as well to jam traffic every day, for everything came and went on city streets through the very middle of town.

It continued, because of the overwhelming dominance of the institution, to handle much of the perishable food for the rest of France as well, including much that was ultimately trucked back somewhere near where it had been grown.

It continued, because it was rough and smelly and rude, to be a border between the west of the city, growing richer and bigger, and the east, growing more crowded and peopled but no richer.

Les Halles also continued to be the source of superb food, of marvelous animation, and created an attractive and engaging part of Paris.

Most of the market was moved early last year, when congestion got beyond all coping. The move and its planning took 10 years and still is far from complete. It”s hard not to think Haussmann would have done it in as many months.

Les Halles was a success. Of course. It served well for a hundred years, overcoming its problems. That is as much as you can ask of any piece of city planning.

But, look here. Why did it need to have these problems? Why not put it on the edge of the city and build a boulevard to it, eliminating the daily traffic snarl all through the heart of the city? It was done with the abattoirs, but that was for sanitary reasons. A central market was assumed, I think, to need to be in the middle of things. In fact it would have been more accessible at the edge. In any case, it was never proposed.

Why, then, didn”t Haussmann move the market two blocks and bring in produce by barge on the Seine?

Because that idea had been proposed and turned down several decades before. It was not Haussmann”s way to reopen old fights. He was an accomplisher. He saw himself rebuilding all of Paris, not engaging in discussions of urban theory. He wanted to know as much as he needed to know to get the construction crews moving.

Questions of the type “Why didn”t Haussmann build airports?” are of limited use, of course, but a last one tickles at your mind when you learn the whole basement of Les Halles was built to hold a railroad yard, and yet no railroad yard was ever built, no railroad ever connected. Why not? Surely it would have lessened congestion, speeded operations and moreover have appealed to Haussmann and the emperor as the modern thing to do.

I am unable to give a satisfactory answer. Full plans were drawn for linking the market, via an underground tunnel, with the circular railway that ringed the city. It was not a particularly intricate plan, nor expensive as Haussmann projects ran.

Haussmann has an excuse, perhaps. After all, he had just built an elaborate network of through streets, and properly anticipated, several decades of grace before congestion really took hold again.

But why was it not done later?

It is a question that recurs and recurs. Why didn”t Haussmann”s successors take the logical next step on a dozen projects? For it is true that they did not. Until very recently the streets of Paris have been as they were. The parks, the sewers, the water, have not been changed. It is a scandal, much proclaimed and little acted upon, that the housing is the same as a hundred years ago – fewer baths, smaller space, older buildings than any other hugely rich city.

One explanation of the inaction is this: Paris had already been renewed, why do it again? Institutions so firmly started. by Haussmann seemed to acquire their own logic, even a certain inexorability.

Also, it was a long time before people forgot how much they disliked some part of Haussmann”s era. Diatribes were still being written after the turn of the century. There was probably a pretty strong current running against putting another “accomplisher” into power, likely to tear down their houses without asking them.

The mode of operation switched from the stampede to the dragged foot. Studies showing the pressing need to move Les Halles, for instance, have been published regularly since the first decade of the century.

The city seemed to recognize what was needed, but then to be unable to pull together a concerted plan of action. Housing and traffic congestion are the most important continuing troubles. I would have used them for my example instead of Los Halles, but the necessary qualifiers would have made direct explanation tedious, and the market may be taken for a type.

The Metro is the most substantial city feature to postdate Haussmann. It was built in 1900, 40 years after London”s first tube. It was built by private firms, to a questionable basic design, and many shortcuts were taken. The urban rail system was divided in half, arbitrarily, from the start. In the 1930s one half, the ring railway, which had carried 39 million passengers in 1900, was dropped. It was far easier to build the Eiffel Tower and hold expositions than to figure out what the city might need. That ring railway could solve many of the city”s current traffic woes.

Paris city governments may be excused for being distracted. Since 1900 the city has seen two world wars, an enemy occupation, and worldwide depression, as well as some instability of national governments.

Whatever the cause or excuse, decade after decade the city got by with adding a few more staff members to carry out what Haussmann had set up. Americans, I think, wouldn”t be able to keep their hands off something as powerful as Paris for so long. It”s not our way to say for very long “It”s good, let”s enjoy it.” Seeing all those men employed sweeping streets and raking parks makes us think of street-sweeping machines and tractors.

But Paris, for the first half of the century, retained a stable population, which always means less for a city to do. The trees continued to grow and be pollarded. The large scale things a city must do went undone. They were not so urgent. The city was aging well.

In the last 25 years the nagging sense that Paris is not quite what it used to be has grown harder to ignore. The case need not be explained too fully. It is the same here as in many a city.

Cars are everywhere. To an American the traffic jams are peculiarly maniacal, but it may just be the different ground rules. Along with double parking and parking along the center lines of streets, drivers also park on the sidewalk, apparently with impunity. It is a barbarism.

Houses are too few, and they cost too much, and they are the same old houses It pays to build new houses only for the very rich, and then only sometimes.

Organization is basically the one Haussmann set up for a city of 2 million. Of a total of nearly 6 million, about half now live outside the formal city boundaries. Here suburbs don”t mean local autonomy so much as second class citizenship.

Transit is still designed for Haussmann”s city. It is the vicious circle of aging equipment, fewer riders, greater reliance on cars that have no place to go and no place to stop.

It is the standard city picture.

The reason I mention it is not to share my depression about city ineffectuality, but to propose a last way of looking at the Haussmann renewal:

Should it be done again?

The question is far from idle. Paris is acutely aware it is losing both population and. industry. That is the beginning of the classic pattern of municipal defeat: not enough people to pay for the services and improvements needed to attract more people.

And since there has been a long period of municipal inactivity many people think they have a strong case finally to demand a new school, finally to have a new park, finally to find an adequate apartment. The people who cannot do it in Paris, which is most people, are living outside the city.

Paris is becoming, slowly, a city of the very old and the very young, and seems as impossible to most middle class, employed, responsible citizens as Manhattan or downtown Washington.

“Faced with this relatively unfavorable evolution,” a “state of the city” paper said a year ago, “requirements do not cease to grow. This is particularly so for city services, where we have to catch up after a considerable delay. Far from taking advantage of past affluence, Paris for decades had fallen into a lethargy from which it has only awakened in the last 10 years.”

What happens next?

“Must Paris confine itself to the role of administrative capital, ensconced in the shadows of glorious vestiges, asleep in the opulent shroud of a museum city? Must it be a combination of Washington and Florence? Indeed, must Paris resign from its current diversity; must it substitute a position of influence founded only on carefully defined objectives?”

It is not the greatness of Paris that is challenged, the report finds, but the simple competence to go on being a metropolis. Undoubtedly Paris will change,

“…but will we always be late for the revolution? It is just when these themes (of the great, and perhaps too-great economic and cultural dominance of France by Paris) have become slogans that the reality they were intended to convey begins to be not quite true any more.”

The solutions proposed, and in fact begun, are almost a caricature of Haussmann It is as though the main threads of his work were transposed a century, stripped of their thoroughness and style. (And of their verve. The notion of a current prefect giving a party in Hotel de Ville that didn”t break up until 10 in the morning, when all the leading national and. diplomatic lights would be seen waiting their chauffeurs on Rue de Rivoli, is bizarre. Hotel de Ville is now where the bureaucrats go to work, like any other city hall.)

The through street to reduce congestion is the first element of the Paris program, as it was with Haussmann. A close-in ring road is three-quarters complete, and divided highways line more and more of the Seine. The cost, as a proportion of the overall city budget, is huge. Roads are devouring the budget and the city. Every year it becomes more difficult to reach the Seine on foot.

Housing, again as with Haussmann, must be in big chunks. Now they are called new cities or grandes ensembles, depending on whether you are pro or con. Like Haussmann”s housing along the boulevards, they are an attempt, in the style of the day, to get a lot of housing built. It works somewhat for the bourgeois and not much for anybody else.

In government organization, too, this superficially attractive analogy between our own day and Haussmann”s holds true. Paris, which had overflowed its boundaries and fragmented, has been reunited – federated might be a better word – under a single Prefect of the Paris Region. It is the first rationalization of the forms of government since Haussmann created the last eight arrondissements.

There are two further points to be made, and perhaps Les Halles will again be as useful a device as any to do it.

First – The analogy is quite false between Haussmann”s renewal of Paris and the current activities.

Second – The current program is a solution of Haussmann”s problems, and of immediately post-war problems, but only tangentially of the problems that will face the city during the decades during which these buildings and institutions will stand. We are not in a period of clear foreknowledge.

The location of Les Halles could have been better from the first, and became impossible. It has now been relocated to Rungis, next to Orly Airport. The only access was up the single-most crowded highway in France. It was immediately clear a second highway would be necessary just next to the first, and it has been built.

It is an improvement in efficiency over the middle of town. It is still like requiring every piece of food to travel the last 15 miles of the New Jersey Turnpike – no matter where it comes from, or where it is going within New York, Connecticut and parts of Massachusetts.

All the Haussmann things at once – bench, trees, urinal, and fancy ironwork, jammed in among the cars that travel his streets.

The real nut of the problem wasn”t even discussed, so far as I can learn. It is this: Why do you need a central market, anyway?

Los Halles did not get the way it was to be quaint and attract tourists. A grocery man had to be able, early, each morning, to buy vegetables, eggs, cheese, salami and canned goods, each of which is a different wholesale specialty. The market had to make all these things, and breakfast, available to him, and give him time to get back to open his shop at 7:30 or 8 o”clock.

A market in the middle of the city, selling everything, is the obvious answer.

Today, however:

Refrigeration has reduced the frequency of wholesale marketing. You can keep cheese a week instead of a day.

The truck has made central location a liability. Far easier to drive 15 miles on a highway than 10 blocks around Les Halles.

Increasingly, the grocer doesn”t go to market at all. More often than not today it is the wholesaler buying at Rungis and delivering, while the grocer sleeps to some decadent hour like 6 o”clock.

The delivery firm likely sells only eggs or only vegetables. Fish trucks are nothing but in the way for the man interested only in eggs. The egg firm and the fish firm would have no cause to trade with each other.

Rungis has solved the congestion problem, albeit expensively. Increasingly, however, it is not a market at all, but a dozen markets side by side. As fewer and fewer customers need both camembert and pears, the reason for a central market disappears.

It might well have been cheaper and more efficient to develop a dozen special purpose markets around the city, but it was assumed there would always be a central market because there always had been one.

Haussmann”s abattoirs, too, are being moved, or rather rebuilt next to the old site. It is the same story. The new will be a glorified, modernized version of the old. The slaughter of animals, here as in the U.S., is more and more carried out near where they are raised. It saves two-thirds on the shipping costs. The new abattoirs will be a 19th century solution, updated in style but not in type.

Paris is building through roads and parking as fast as it can afford to. Many people, including me, think it will be impossible ever to supply enough super highways through the city to satisfy the need. Whether this view is right or wrong, it is too widely held to be simply ignored.

Basic disagreement about how to make a city better was not part of what Haussmann faced. Now, however, it is unclear in the most elemental ways whether a given public project, say a road, will make things better or make them still worse.

The five-year plan for the Paris region presents some new alternatives. The satellite new cities it sees rising from the outlying fields seem overwhelmingly difficult to create. What is proposed as their structure and design seems terribly pedestrian, perhaps even a recreation of problems.

Without agreement on what should be done, it seems hardly likely the resources for broad gauge renewal will be assembled. And. there is certainly little agreement. A proposal for more underground parking – hardly controversial, you would think – raised. such a brouhaha that plans have been shelved.

That a project could be stopped by citizen opposition is another difference from Haussmann”s era. He was a driver, a bull. He only answered inquiries from legislative committees when he chose to. If Haussmann could raise the money for a project, he went ahead and built it.

That a project could be stopped by citizen opposition is another difference from Haussmann”s era. He was a driver, a bull. He only answered inquiries from legislative committees when he chose to. If Haussmann could raise the money for a project, he went ahead and built it.

Once, he tore down the newly constructed house of a senator to provide room for an adequately wide sidewalk.

Do you picture that happening in Washington? It wouldn”t happen today in Paris, either.

Paris is back to being a city like everyplace else, doing what it can, often answering yesterday”s questions tomorrow. Haussmann”s Paris will finally be improved, but it will be a piece at a time. There will not soon again be another tremendous rebuilding.

Piece by piece with constant public discussion is a slow way to get anything done, and it certainly would not have produced the Paris that has been so admired for a century. But a city running at peak efficiency may preempt and consume too much of the lives of its citizens.

Photos – AB

Received in New York on March 9, 1970.

©1970 Andrew Earl Barnes

Mr. Barnes is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published, with credit to Andrew Barnes, The Washington Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.