PARIS – For 800 years the central market of this city and much of France, Les Halles, will soon be no more.

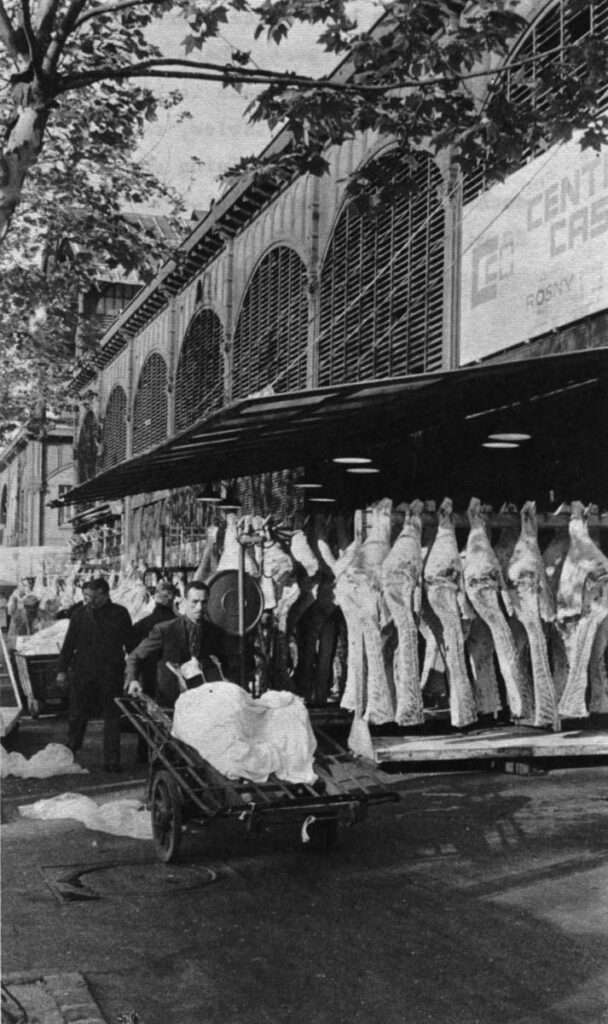

Vegetables, fruit, eggs, cheese and flowers are gone. Only meat remains, and it too will soon be moved.

With them will go the streets jammed with trucks, the sidewalks and bars jammed with strong men.

Left behind is 100 acres of the busiest center of Paris, and a fight over how to rebuild a city without destroying it in the process.

At 6 a.m., up the Autoroute du Sud to Paris, all three lanes are dilapidated Citroens, shiny vans and three-wheeled scooters, crammed with Spanish oranges, Moroccan tomatoes and very fresh eggs for a city that likes to eat.

Grocers, restaurant buyers and, increasingly, central provisioners have since February made their dawn drive to Rungis, next to Orly Airport, where they park in vast lots and walk into utilitarian-modern sheds to choose among the endless stacked crates of just-arrived vegetables, cheeses, eggs and fish.

Bargaining done, supplies are quickly loaded at wide docks, the last crates tied to the roofs. The roads are open for the 20 minute drive back to a city just beginning its day.

Les Halles, 12 open pavilions surrounded by hundreds of food merchants using the ground floors of old buildings tightly packed on winding streets, strangled in its traffic and was unable to grow. Smack in the middle of Paris, every buyer or seller had to cross the most congested part of the city to get there.

Demands that Les Halles be moved are hardly new. They began in the 1850s just after the market was built in its present form. The arguments have changed little since. The streets are too narrow, barely wide enough for a car, let alone a truck. There is no rail connection. When new facilities are needed, there is no place to put them. And the traditional ways of operating are so set that modernization was next to impossible.

It was this bustle and jostle of work and pleasure that made Parisians love Les Halles and fight the removal. It was without doubt alive.

Even now, with most of the market gone, the men in white coats blotched with blood, caps pulled down over their ears so they can balance the sides of beef on their shoulders with their heads, brush past shop girls delivering bread, and clerks on their way to work.

From 7 o’clock on there are children in the streets, running errands for their families who live in the flats over the markets.

On Rue du Jour, in back of Eglise St. Eustache, a central point for Les Halles, men were cutting pig carcasses with power saws hung from the ceilings throwing feet one way, sides another. Their workroom was the entirely open ground floor of an old five-story building. At 8 a.m. a pretty girl of about 20, apparently the bookkeeper, arrived for work. Work stopped while she shook hands with each of the butchers. She disappeared to the glass office at the back, and work resumed.

Two hours later, a tractor trailer delivering carcasses to the same place blocked all traffic for a half hour as it unloaded, then took another half hour to bend its way around the corner into Rue Montmartre around another double parked truck.

The same morning, it took 10 minutes to clear a traffic jam so two fire trucks could pull out of the firehouse into Rue Montmartre.

There was no yelling or waving of arms. Such delays are usual in Les Halles. (Apparently the fire was not close by. There was no smoke in the air.)

Renewal

At least a substantial part of Les Halles – the central pavilions and some of the surrounding – will be leveled. It will be like American attempts to renew the centers of cities. But it also remains busy, even overcrowded, unlike the vacant acres that identify American urban renewal.

The attempt to maintain this business and life through the renewal process has produced controversy and rhetoric. The “belly of Paris” is now, to the speechmakers, the “heart of Paris.”

A City Moving Out

The Paris region is growing. Population was 6.8 million in 1936; 9.2 million in 1968. Physical expansion is even more dramatic. Out any highway from the city the huge hammerhead cranes rise over fields still planted with timothy, lettuce and corn. The papers are full of ads for places like Grigny II, “a new concept in living,” that appear to be apartment complexes with shopping centers.

But the city itself is losing population, down 7 per cent between 1962 and 1968, while the suburbs are up almost a million people, more than 16 per cent, in the same period. (The region had 2 million inhabitants in 1857 when the shape of Les Halles was set.)

This pattern, so familiar in American cities, finally forced the hard decision to move Les Halles.

One device used to make a politically unpalatable move acceptable was what was called the first extensive public opinion poll in France.

A firm was asked to survey people who could be expected to use Les Halles. Fewer than half said they ever used the market; only a third of the merchants in the growing suburban zone ever used it. Also, an individual merchant had little use for the variety offered in one place; if he wanted butter and cheese, the merchants buying vegetables were simply in his way. Not only modern transportation, but specialization of merchants had reduced the need for a comprehensive market in the middle of the city.

Paradoxically, there was another opinion, virtually unanimous. Everybody wanted Les Halles to stay. Even those who didn’t use it and might use a better facility, said they liked it where it was. It was part of Paris.

The decision was made in 1959, then again in 1962, allowing six (later seven) years before the move. There were protest meetings, bitter speeches from the leftists in city government, but the plans went forward.

The New Markets

Rungis, south of the city, is 500 acres on a super highway and a rail line. Dozens of huge open buildings with modern loading facilities handle the daily tons of produce with ease.

La Villette, on the north-west edge of the city, has had the bulk of the city’s abatoirs for some years. New facilities nearing completion will add butchering, bulk sales, and secondary facilities such an tanneries. Again, highway and rail access will be easy.

The new markets work better than the old. The move has become accepted. There are no protest signs on their new concrete walls.

A New Fight

The plans for development of the now vacant Quartier des Halles have already brought a fine dispute. Last year six architects were asked to submit models. Although they varied in detail, each proposed tearing down most of the quarter and building a sweeping new complex of curved glass and steel. Unveiled in October, the outcry brought almost immediate rejection from the city council. Citizens marched on city hall. Posters went up on walls. The leftists in the council said it was bureaucracy trampling on the poor.

The area to be leveled was cut to about 32 acres, and a major government finance center was eliminated. A much higher proportion of the existing buildings will be rehabilitated.

As it now stands, first construction will be a huge new library on an open square that has been used for parking. Next will be a major terminus, underground, for an express metro into the suburbs. The other major development still planned, although its schedule is less certain, is a center for international commerce to be built around the Bourse du Commerce, which will remain.

The planners and the protesters agree, at least in words, that the distinctive character of the quarter will be maintained, whatever that means in a section where the very reason for its being has been removed. Although rundown housing must be improved, it should still be available to the relatively poor people who now live in it. The Bar-Tabacs must remain.

Boutiques, book stores, parks (10 per cent of the area where now there are none) and other human-sized aspects will be added.

New housing will be made available in time for old residents to move in without being forced out of the quarter. The construction itself will be made a spectacle to preserve the area’s liveliness during rebuilding.

An information center has been opened, with a 20 by 80-foot model in meticulous detail. Meetings are held there to explain to residents and others what is going on.

The words of agreement have not stilled fears that the area will be changed beyond recognition.

A council of all the businesses in the quarter issued a statement Friday complaining they were always being told what would happen, never asked.

A beautiful book has just come out tracing the history of all the buildings, some dating to the 14th century, and pleading for their preservation.

The “urbanisme” columns of the papers and magazines hardly let an issue pass without quibbling about whether the metro station should be built so soon, whether international commerce is appropriate to the area, and raising again the specter of a glass-fronted neo-Park Avenue.

Two more public opinion polls have been taken. One, of the whole Paris region, found wide agreement that Les Halles is dirty, ugly, has a “negative image” and should be completely torn down. The other, of residents of the quarter, was all for renewal, but understood that to mean cleaning and painting. There was almost no understanding of the extent of rebuilding planned.

All of which leaves Paris authorities in a position familiar to their American counterparts:

The main clearing has been done (the market removed) and they need to go ahead. If they do not, the quarter will surely die.

But if they go ahead without agreement from the citizens, the quarter as it now exists will likely die anyway. And agreement from the citizens, or even a definition of who the citizens are, seems impossible.

Les Halles, 6:30 a.m.

Rue Sauval is still dark. The sidewalk and half the 10-foot street are blocked with steel carts on wheels. One is filled with calves’ feet, another with calves’ heads. At the rear of the open abatoir men are working around an open fire. Other men crowd around the glass cashier’s cage, writing on clipboards.

In the bar next door men in long blue smocks smoke yellow cigarettes and drink red wine. The sign in the window advertises onion soup, but nobody is having any, The conversation is general, and the men appear to know each other and to be at home.

Just down the street begin the steel-shuttered fronts – fromage, creme, buerre, legumes – merchants moved to Rungis.

Les Halles, 1:30 p.m.

All 14 tables outside the cafe on Place Ste. Opportune are occupied, and the man in the dirty white apron is frying the day’s special, Vienna sausages, at the small stove in the stall to one side. The patrons – two women resting from their shopping tour on Rue de Rivoli a hundred feet to the south, a man in a business suit in a hurry, two young people drinking wine and enjoying each other – look out over the small square.

The metro entrance in the center is in constant use. A bank is open to the left, customers coming and going. The other sides at street level are the blind fronts of closed vegetable merchants. Women and children are visible through the open apartment windows above.

Rungis, 7 a.m.

The fishmonger stands over a wooden case piled with flat, glistening fish. He wears a wool cap, a blue workman’s suit and apron, and boots. The room could be an airplane hangar at nearby Orly. Another man, similarly dressed, comes up, they talk, a note is made. Nearby a woman arranges snails in neat rows on a counter. Across the vast space perhaps a thousand people are meeting, trading, walking on. There is little smell and no debris, for the cleanup is constant.

Up and down the aisles among the buildings men are riding tiny-wheeled bicycles to get from one seller to another. Rungis hopes to rent the bicycles to tourists as well, helping to make Rungis the attraction Les Halles has been. So far it has not caught on. They fear it may be the three franc rental fee.

Received in New York June 4, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow. This is his first newsletter.