PARIS – The high rise towers and garden apartments of Sarcelles would seem quite ordinary outside any American city. They mark the familiar sleepy town boomed with city people. In fact, with its attractive trees, somewhat distinctive architecture, walking-distance shopping and general air of liveliness, Sarcelles seems a little better than ordinary.

But here in Paris Sarcelles is: famous; shocking; the topic of novels; and the favorite horrible example of every urban reformer.

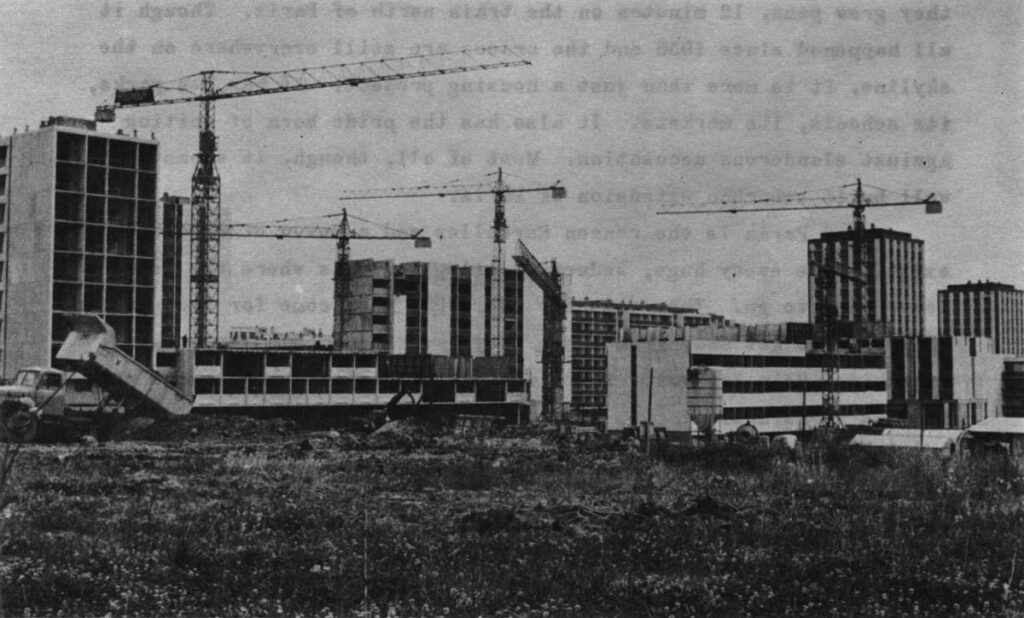

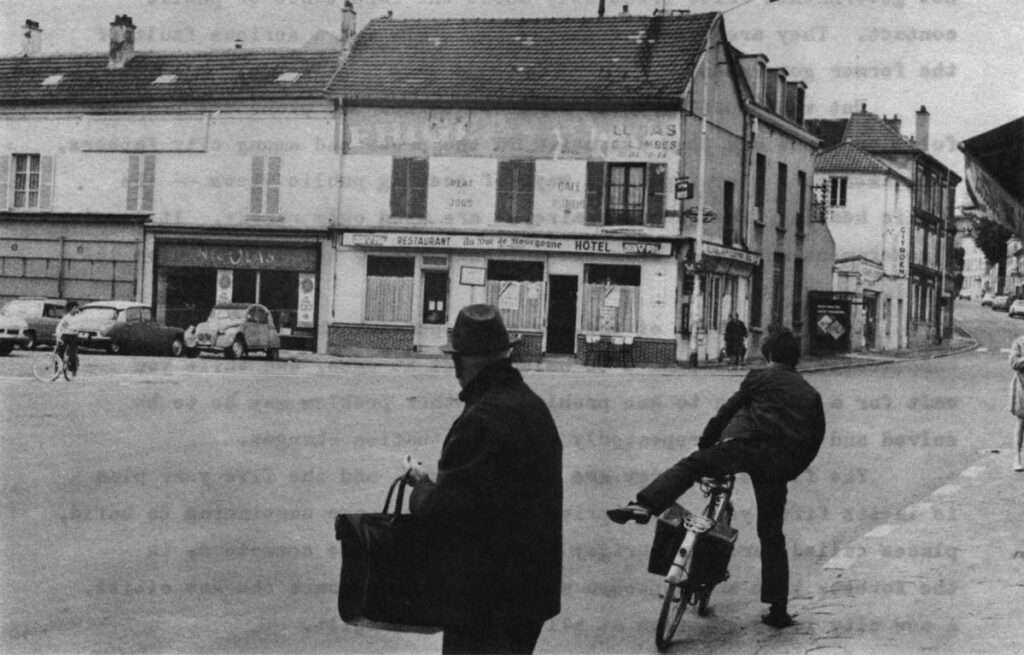

Aside from all these things, Sarcelles is an apartment city of about 50,000 residents, plunked down next to a town of 8000 where they grew peas, 12 minutes on the train north of Paris. Though it all happened since 1956 and the cranes are still everywhere on the skyline, it is more than just a housing project. It has its parks, its schools, its markets. It also has the pride born of uniting against slanderous accusation. Most of all, though, it seems a well built suburban extension of Paris.

And Paris is the reason Sarcelles and a dozen other places exist. Like every huge, seductive city, Paris is where the young leave home to go. They come for the work, they come for the glamour, they come to get away from where they have been. But there is no mistaking their arrival. There are five Parisians where there were four 14 years ago.

That is a growth rate about equal to the proportion of growth for all American cities between 1950 and 1960, and would be mild indeed for the capital of an underdeveloped country. But it is far steeper than the French average, and followed decades when Paris grew hardly at all. Since Paris itself is full, probably overfull, the new people found homes in the suburbs.

This has become the most common story in cities of all sorts around the world. And in Paris, again as in much of the world, nothing was ready to receive the new people. Here it was because for half a century statesmen, occupied with great world events, allowed localities to be administered as they always had been, by solid, stable bureaucrats who made few changes and thought few to be needed.

But, ready to adapt or not, when about 2 million new people arrive in a city that already doesn’t have enough rooms, nobody is immune from the clamoring pressure. More Paris had to be built.

Two Ways of Building

Sarcelles was one method of enlarging Paris. Although it would fit most definitions of a “new city,” the very idea of calling it one is ludicrous. It is called a grand ensemble, a term of opprobrium about like “housing project.” Both its design and the way it was built have been criticized.

The new way of building some more Paris is typified by Cergy, which everybody calls a new city although it doesn’t exist. Its first building, an upside down pyramid to house the new city’s government, is nearing completion. It is one of two buildings in an alfalfa field overlooking the River Oise. The other houses urbanists planning the rest of the new city – its links with Paris, its links with other new cities, the stages of construction and a hundred other variables.

The Post-War Situation

There was little time for such comprehensive care in the early 1950’s when it became unmistakable that population was growing and the housing shortage was acute. It became politically imperative that a lot of houses be built at low per-unit cost, and quickly. The demand had to be met, but nobody was much interested in doing so.

There were no private construction firms willing or able to step in. Local government, which might normally be expected to solve such a problem, was as a whole very little prepared to do so. Communes were (and are) weak. They are too small to support the staff to plan and bring off a substantial public works project. Moreover, local officials had become accustomed to waiting for the central government to act. It had been found easier, since nothing could be done without involving the central government, to simply hold off until the central government was ready to do it all.

Paris, in this as in so much, was the epitome of the national pattern. The basic unit of local government was the Prefecture de la Seine. (To say that forgets about six levels of vestigial government, and six others firmly in control of one aspect of life or another, like the independent police force.)

A Government Unable to Act

The Prefecture de la Seine had become, in the judgment of the present Paris government, elephantine. For decades it had taken on and made routine chore after chore for the tens of small communes of the Paris region. It supplied water and licenses and roads, but not too many or too fast. It had grown fat on decades of ample resource for small demand. It had also grown too big and slow even to see the need for major change, let alone act on it.

While a prefecture is the operational level of local government, it isn’t, in fact, local government at all. The prefect is appointed by the national government, moved from place to place rather like a career diplomat, and has sometimes remained more concerned with national influences than local.

This was the very picture of a situation where everybody wrings his hands and keens and does nothing. But the people didn’t go away, they kept on arriving. One means found to actually get some housing built, the one that produced Sarcelles, was entirely independent of traditional government.

A Backdoor Method

A national government agency, the Caisse des Depots, had since 1816 been in charge of keeping the money for several other agencies, and to a certain extent surveying their operations. In this way it had some role in supervision of loans made for such things as housing projects, although it had no direct responsibility and had certainly not been created to be a housing agency. But it was aware that houses were needed and nobody knew how to get the job done. It also had available cash.

The Caisse des Depots, in 1954, stepped in to create a subordinate yet independent agency (une filiale) called the Central Building Society (known always as S.C.I.C. and pronounced ‘seek’). It was charged, in just about these terms, with doing what needed to be done to get a lot of housing built.

The last step in this intricate chain dangling housing down from the national government, was for S.C.I.C. to form a mixed society. That means giving a piece of the action to the big banks, the unions, the chambers of commerce. It also means that the society becomes, legally, a private person, freed from some of the restraints that inhibit government action.

To oversimplify: a national banking agency incorporates one of its branches and starts to build houses when the national government cannot find another way to solve what is essentially a local problem.

S.C.I.C. moved ahead, and one of its first projects was in Sarcelles, a small town that had been insulated from Paris growth because it was tucked in behind the unfashionable working class and industrial suburb of St. Denis. There it found a cheap 420 acres.

An attempt was made to involve the little town. Sarcelles was asked whether it wanted to set up the building society under a somewhat different procedure that would give the town a strong voice and require substantial investment. The town, never having even heard of anything on the scale proposed, declined.

Sarcelles Rises

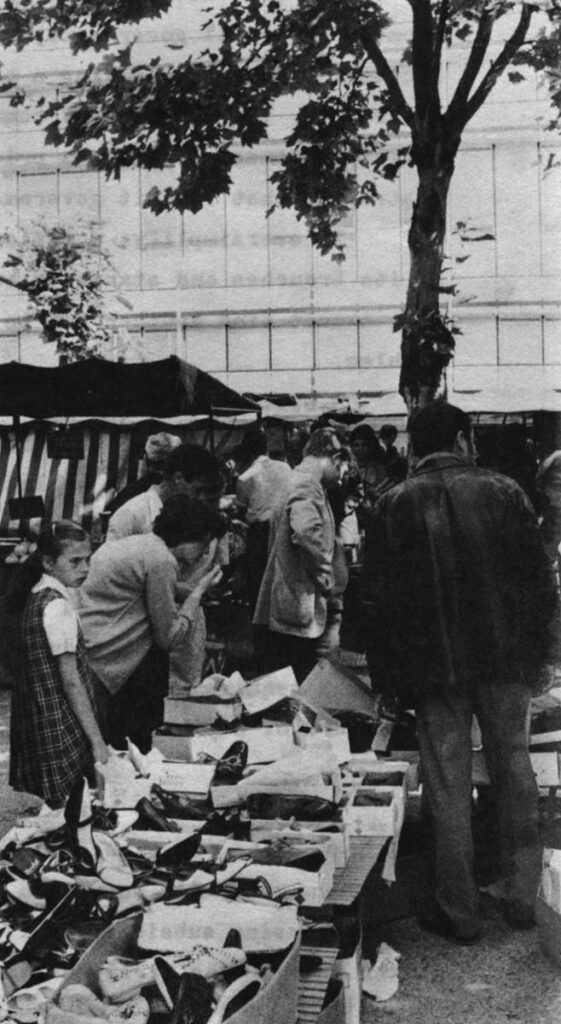

When it came to building, S.C.I.C. did indeed know how to cut through the red tape. All multi-family housing, most for rent (rental range of $40 to $100 a month) the buildings took advantage of all the housing subsidies available, all the economies of large-scale construction. The first buildings are pretty neuter-ugly, the more recent ones have more style. All are laid out on a right angle grid street pattern. The apartments are of medium size, just right for a slightly crowded young family. The market is apparently unending. There are never any vacancies.

Sarcelles was planned, not in the comprehensive way that was to become fashionable, but to provide a lot of housing without committing obvious errors of layout and design. There have been blunders. A central heating plant has been completely rebuilt three times because of faulty growth estimates. But the impression walking in Sarcelles is of order and design in sharp contrast to an American suburban housing project, where it can sometimes seem that nothing at all is convenient. And 50,000 people housed in 13 years is no small achievement.

Reactions

The fine French fuss that followed the success of Sarcelles included two novels (only one of the authors claimed to have stopped on his way through town), a string of the-truth-as-revealed-by-us-exclusively newspaper accounts, and finally a detailed and readable defense by the residents.

The general line of attack was that Sarcelles is an egg crate world, where a person’s individuality counts for nothing, where everybody has sold his soul for uncracked plaster and is sorry he did it. The median age was widely reported to be 12. In fact it is low, but it is 21.

Interviews with unhappy wives were published. The desolation of the train ride through St. Denis was described. Sarcelles became the hyperbolic city of lost souls.

Sarcelles was unquestionably pray to the evils of building all at once from scratch: at one time there were too few bread stores and long lines, schools were several years behind tenants at some periods, necessitating long trips; streets were built after buildings.

By and large, though, it appears to have attracted a young, fully employed, fecund, mobile population that was having severe trouble finding a place to live.

Little matter that much of the criticism of Sarcelles was unfounded, that residents said it was a place where life could be lived, or that there were no vacant apartments. Sarcelles got, and keeps, a bad reputation. It can now be cited without explanation as something to be avoided in future.

New Government, New Cities

Dislike for Sarcelles and places like it, and realization of how little the Prefecture de la Seine was able to govern, brought a substantial change in the forms of local and regional government in the 1960’s, as well as a radical shift in the way of building more city.

The Prefecture de la Seine has given way to six local prefectures and a regional prefecture. The six are to remain in touch with their citizens, providing a more responsive day to day government. The regional prefecture is to plan changes needed over a period of years, and get them started.

Population growth remains the central consideration in the planning. Provision for the city things that Sarcelles ignores – subways, theaters, recreation, specialty shops, work close to home – has been added to the plans. The device for achieving this new, better growth is the new city; its method of achievement is urbanism.

I am unable to give a good definition of what is meant in France by urbanism. It has some of the same connotations as city planning in America, but implies more power to actually make a city, although it is new enough so very little actually exists as its result. It also carries a little hint that urbanism is what the writer thinks good, while everything else, including the work of other urbanists, is sprawl.

New City, too, has become an almost useless phrase, so contradictory are the meanings it must convey. What is meant here is unlike the city built in a new spot from scratch; rather it is a node, a thickening of population density and city services, within a continuum of greater Paris. Cergy, a little more than 20 miles from Paris, is one of five in the current five-year plan. It will, incidentally, be the seat of the local government controlling Sarcelles.

A stunning site has been picked for Cergy, on hills overlooking an elbow of the Oise. An artificial lake will form an aquatic park. Land use controls, both to slow development outside the proposed city and speed it within, have been instituted. Plans have been drawn for a city of 1 million. Two public facilities, a road halfway to Paris and the city hall, are well along.

Streets, schools, parking, mass transportation, and recreation will be built by the government. It is intended that each section in turn will be finished enough so life can be lived without 20 years of mud. Several thousand jobs in the prefecture itself will exist right from the start as an inducement to merchants and contractors.

There is really no question at all that Cergy, if it approaches the plans of its designers, will be a more imaginative, more urban place to live than Sarcelles.

The strongest case for Sarcelles as a way of dealing with population growth is that it actually exists, was built timely, and is better than crowding into the old houses that were its alternative.

Sarcelles may, in fact, represent the attack on the French way of life that its critics claimed. Its supermarket, for all that it exists next to dozens of shops, likely foretells the death of two grocery shopping trips a day, and the tiny stores that supply 100 grams of this and a small bunch of that.

Efficient apartments that can be cleaned and cared for quickly do probably spell the death of the pattern of all good women staying home to run the house. Roads and parking places do encourage people to use cars. Dress is more casual and children seem freer than in Paris.

Change in the patterns of life, even when it is necessary, overdue and sought, is disquieting. Sarcelles was open to criticism as the visible embodiment of this change, but it didn’t bring it. Sarcelles is, in fact, not very innovative at all. It is a well executed housing project.

It still shows the odd auspices that created it. S.C.I.C. still runs everything. It owns not only the buildings but the streets, the streetlights and the statuary. Every bill is ultimately paid to S.C.I.C.

Residents are pushing for political independence and self government (Home Rule? Free Sarcelles?) and the town has belatedly asked the urbanists to draw up a plan for uniting the old center, an undistinguished place, and the apartment city. The plan has been drawn. It also shows an employment center, much more recreation space, and more thought for the whole range of things that should be part of the greatest city in France, even in its outskirts. But the problems of imposing a plan on an already built place are at least as great as those of making a new place.

The case for starting fresh, with a new city, is obvious enough. The case for Cergy as a new satellite of Paris is perhaps even stronger. Unlike a housing development, it will offer many of the things for which people move to the big city. At the same time, it recognizes the overwhelming dominance of Paris.

Its auspices, too, would seem an improvement. Instead of the government adopting an institutional disguise to do through the backdoor what it should do straightforward, it is an attempt to combine comprehensive thought with power of execution.

Paris is indeed a region, and to have a government able to recognize it as such must be a step toward better government. The new governments write frequently about the importance of public contact. They are right in saying that this was a serious fault of the former government.

But while public involvement is talked of, plans are presented fully complete and then discussed in the press and among city fathers. Even America’s very imperfect ways of seeking public views – the public hearing, the questionnaire – are used only rarely. It remains a government appointed from the national level, not elected from the local.

It’s the nature of the new city approach that all the complicated variables have to balance out at once, and while you wait for a solution to one problem, another problem may be to be solved and resolved repeatedly as the situation changes.

The fields of Cergy are still plowed, and the five year plan is in its fifth year. The private developers are continuing to build,, places called Parly and Grigny II for high income commuters, in the forests that are supposed ultimately to surround the new cities. A new city is no solution at all if it isn’t built.

Photos-AB

Received in New York on August 1, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.