PARIS – Somebody else’s slum is hard to see.

Poppincourt, the 11th Arrondissement, is a case in point. East of the Marais, the oldest quarter of Paris and target of preservation and rebuilding efforts, south of the Goutte-d’Or, which everybody known is a slum, you can spend a day walking the tree-lined boulevards of Poppincourt seeing nothing but bourgeois Paris.

Up Boulevard Richard Lenoir from the Bastille, then down Boulevard Voltaire from Place de la Republique to Place de la Nation, the aspect belongs to Baron Haussmann, the Robert Moses who, as prefect of Paris at the end of the last century, widened the boulevards, built the parks and spurred the city’s last real residential building boom.

The six-story buff-colored buildings with ornate ironwork facades wear their age easily.

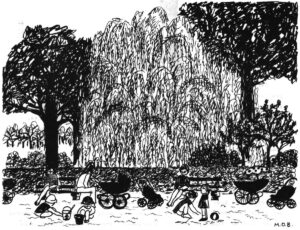

And as on all such Paris streets, shopkeepers stand in their doorways admiring the sun after a week of rain. Women push the remarkably posh perambulators that are the Paris standard, making their daily purchases. Old people sit talking on the benches at the curb.

Off the boulevards the streets are narrow and bending, always darkened by the six, seven and eight-story buildings that seem to impinge on their sidewalks, forcing people and trucks and motorbikes to compete for what little space is left.

But here too the shop-fronts are shining clean. They are washed each morning. The air is filled with the intoxicating smell of strawberries piled high on a curbside cart. The jostling crowds of shoppers take over the whole street. An almost bald old lady pushes aside the laundry that fills her window to watch, becoming herself a part of the picturesque scene.

Swept along by the buyers and hawkers, or sitting at a cafe, you understand why the guidebooks send people here. It is a vital, colorful place to pass time.

It in also a slum – dilapidated, aged, jammed tight with people.

Some 180,000 people (Austin, Texas or not quite Providence, Rhode Island) live in 1.4 square miles of city. The number of people per square mile is twice that of Paris as a whole, excluding the big parks. (There are no parks bigger than one block in the 11th. Only one is that size.)

The buildings not only look old, they are. More than 93 per cent were built before 1914. Nearly half were built before 1871.

About a third of the dwellings were found overcrowded by the 1962 census. The standard used was minimal.

A third of the flats have their own toilets.

Half have running water in the flat; 15 per cent lack any running water inside the building.

Only 16 per cent of the flats have a bath or shower.

Less than 20 per cent have central heating.

The buildings visible from the streets are by no means all in the 11th. Through the doorway into the courtyard there is another building, often with another building beyond that, and perhaps still again. It is like the pictures that fascinate children of a man looking at a picture of a man looking at a picture of a man…

Poppincourt in where furniture is made. Surrounding the interior courts at street level are the workshops, filled with the whine of saws and the fumes of varnish. Two men carry a sofa frame along the sidewalk. Another gives a. final smoothing to a new antique table.

Tucked into the doorway of an apparently residential block is a man bending over his metal lathe, the dark narrow room filled with the smell of hot oil.

Over the workshops in dark buildings hard against each other are five or six stories of windows. You would assume them to be loft storage, but for the geraniums, the starched white curtains, and the letter boxes in a pitch black stairwell.

Usually it is the oldest people who must climb to the tops of these buildings, carrying their water. The highest flats are cheapest and the old are poorest.

Delivery trucks come and go through arched entranceways. The signs name four furniture companies and a dentist or a lawyer, perhaps a plumbing supply firm. The concierge lives just off the entranceway. Typically, the only natural light in her flat comes through the glass in the door.

In the evening, the factories shuttered, the residents can be seen sitting in the courtyards, talking and perhaps having a glass. While it can be a pleasant scene, it is also about the only place to go. The flats are too mean, the parks are too few, and there are virtually no organized activities, particularly for young people.

Except, of course, the bars, which are everywhere. Each seems to have its own clientele. One will have whole families, infants, children, adults and old people, drawn around several tables pushed together. Another will be all young Algerian men, many of whom have come to Paris to work and found rooms or places to sleep in the 11th. The conversations, always held while standing or walking around, are in Arabic. Another bar will be for black Africans. Another filled with the old residents, men and women dressed up to play cards in the cafe on Saturday evening after a week’s work.

Except for sandboxes, I have not found a single piece of what Americans call playground equipment in the 11th (as is almost true for all of Paris). So the children can be seen at street corner carnivals riding merry-go-rounds. Their mothers play the huge wheels of chance, in hope of winning starchy-dressed dolls or sets of glasses. The fathers stand at the shooting gallery, concentrating on small paper targets as though they were back in Algiers, or in the Maquis.

A late afternoon and early evening costs a franc here and a franc there, mostly just for a place to be. Few amenities are free in the 11th.

But it is the cost and inadequacy of housing that are shocking.

An article some weeks ago in Le Monde summarized a report by workers of the Securite Sociale on the 11th Arrondisement.

Typically an old building, called a hotel, rents a single room to a family for 250 to 300 francs ($50-$60) a month, likely without running water or bath. This represents as much as a third of a working family’s income, for housing that is in no way adequate. It of course costs more than would the unavailable housing designed for low income families.

There are cellars where Algerians and Africans sleep in 8-hour hot-bed shifts for 6 francs.

When whole families share a room, the baby may fare best, because room can be made for him in a bureau drawer. There is almost always a television set, and it is almost always on. It is the only entertainment. But it is a problem, often keeping a night worker awake.

Le Monde told of fights with rats, of no heat and of threatening landlords – stories that would be familiar to anyone who reads the New York or Washington papers. They are the horror stories of the poor.

The most serious health problems in the 11th are two: unwanted babies and mental health, Le Monde reported. There is a resistance to birth control on social grounds, with mothers often preferring to seek abortions. It is the pattern, not the exception, in parts of the 11th for babies to be unwanted.

And on mental health: What do you do, the Securite Sociale report asked, when someone comes to you mentally sick because he faces insoluble problems of overcrowding, lack of privacy and lack of opportunity?

One reason the 11th Arrondissement is not entirely easy for an American to recognize as a slum at first is that some of the most familiar slum patterns are missing.

- The streets are clean. There are no piles of garbage. The gutters and even the alleys are flushed throughout the day. The twig-broom man is diligent. The 11th is cleaner than any part of New York I have seen lately, and cleaner than most urban parts of Washington. The city continues to provide services.

- It doesn’t stink. I have not been inside enough buildings to know about them, but the sense from the street is of fresh produce, coffee roasting, or no smell. The smell of dirty old buildings is lacking. At least some forms of private upkeep continue also.

- Vandalism is not visible. The walls have communist slogans and Pompidou posters, but not curses. The streetlights are whole. There are no broken bottles on the sidewalks.

- In many days of walking I have noticed only two vacant stores. The merchants give every sign of prosperity. While there are the usual gyp-the-poor sales pitches for televisions, food and clothes seem to be sold on the same basis as in any Paris neighborhood.

- Three metro lines provide frequent service and buses are as good as in the rest of the city, so the 11th is less an island within a city than many American slums.

I could sense none of the menace and fear that have come so to mark American cities. Women walk alone at night, and not only streetwalkers. Going through impasses, into courtyards and halls, I have often been challenged by concierges, but never blocked or glowered at by young toughs. I have no good explanation of this, except, perhaps, that fear and menace are self-continuing patterns that have not begun here. Everything, of course, is nevertheless locked with two locks.

The heterogeneity of the place is perhaps the most strikingly unexpected aspect to an American. Not only is it the tended boulevards hard by the dilapidated streets. On one of the most overcrowded streets, Rue de la Roquette, a new apartment house has been completed between two darkened piles of buildings.

A beautiful brand new apartment building has its fine balconies overlooking two sheet metal factories (and of course there are no for rent signs; there are virtually none in Paris).

One building, four of its 16 stories complete, will offer apartments starting at 2200 francs a square meter. That works out to more than $40,000 for a good-sized two bedroom apartment. The sign says the apartments will be symphonies of stone and gold.

Spruce old buildings stand next to dilapidation in many streets. And streets of dilapidation are intermixed through the whole arrondissement.

The largest market in the 11th is held Tuesday and Friday on Boulevard de Belleville, a very tawdry street but a center of life. The city sets up the pipes and awnings for the market the afternoon before, in the paved strip between the traffic lanes. The vendors arrive in the early morning – they have specially fitted trucks from which a huge display is produced in a half-hour.

The goods range from elaborate corsets out of the Victorian age to books, but mainly it is food and cheap clothes. The food is fresh, attractively displayed, and less expensive than in the stores.

The crowd, throughout the morning but especially at noontime, is as dense as it can be. The movement is from north to south, and it is difficult to work back toward something forgotten against the tide of people.

Both men and women are buying as much as very limited space and refrigeration will allow; some carry two and three string bags filled with vegetables, fruits, cheese and meat.

The hawker will likely have only one thing in front of him – “Buy my garlic, extra fresh, two francs the kilo (correct – a kilo is 2.2 pounds and garlic is bought by the kilo).” The shopper buys each item in turn from a different seller. There are some black faces in the crowd, some Spanish and Arabic voices, reflecting the population of the arrondissement.

Between 1 and 2 o’clock the market stops. The structures are gone by 3, and by 3:30 the street has been swept and flushed and is clean.

Much of the 11th Arrondissement is a transposition across 50 years. At the turn of the century a toilet was not considered necessary for a standard city flat. It is those same houses that now are still the 11th.

It is this stable, almost static style that has also preserved much that makes life livable in the 11th, the market, the cleanliness, a basic civility.

From this limited standpoint of the institutions and facilities of a city, much the same could be said of all of Paris. The first half of the century was a time of static population, little building, little innovation, while wars, empire and inflation were the concerns of the city that seemed inexorably to dominate France more completely.

But in recent decades change has come and Paris is beginning to recognize it officially. Population has been dropping in the 11th as in the whole city. Big industry (Citroen and Renault are only the most visible examples) is no longer expected to be the work of most Parisians.

The city is moving west. Disregarding the suburbs (a thing Paris does almost completely though they are now larger by far than the city) where Chatelet was once the center of the city’s activity, Champs Elysees now is. A widening wedge from Les Halles through the 11th and eastward is now being left behind by growth and change.

The city has outlined its plans for renewal, although its powers are even more unclear than in American cities. Instead of tearing down and starting fresh, which is seen as an error of American cities to be avoided, the plan is to remove what is bad and bolster what is good.

Roads and parking are first priority. This means, in 11th, making several of the boulevards into links of a highway network. If they were to isolate the 11thbehind impenetrable walls it could be disastrous, but the planners say they will not. Specific plans are not yet available.

As small industries leave, seeking modern facilities and lower costs, new jobs are being sought in the commerce and service sectors, such as the international trade center planned for Les Halles.

Housing, though, remains a largely unsolved problem. And, patently, something must be done about jamming whole families into single dark rooms without toilet facilities or running water.

While population density is one of the things that makes a city a city, when people are piled one atop the other without privacy or even sleeping space, all of life suffers. Old people and young families are the least able to adapt to the garrets and attics where necessity places them.

Every politician, every “urbanist,” every city pronouncement talks about housing, says it is the priority of priorities, and the problem will be solved within the next three years. The library has a full range of such manifestos.

The tremendous shortage remains. Less has been done about it here than in other European countries. A decision would have to be made at the national level to pay the cost of housing the poor adequately, and it has not in fact been made. It would be an expensive decision.

Virtually all housing built in France today except frankly luxurious has some degree of government financial involvement, with far greater inducements offered to builders of housing for low income residents. But it remains a better business deal to build for those who can pay.

And when only one apartment in three in all of Paris has its own bath, it seems likely the 11th Arrondissement will get no special attention. The situation there is only twice as bad.

The approach to renewal is the antithesis of America’s pattern of tear down and replace, isolating what is new from contamination by its surroundings.

And it may be that if the strengths of the 11th – variety, attractiveness, sense of neighborhood, accessibility – can be reinforced, by new commerce, by better health care, by a new library (one is talked of), that change can begin, a sort of renewal take place, without a frontal attack on the grossly inadequate housing in the arrondissement.

It is indeed the worst buildings that are being demolished to make room for the new apartments. But they house different people.

Adequate housing for the poor – newcomers to the city, laborers, old people – could be fitted into a pattern of ameliorative renewal, but it will not happen by itself, and it will not be done cheaply.

As things now look, and nothing is even thought to be set, renewal of the 11th will be a removal of its worst housing problems to someplace else, not a solution of them.

Received in New York on July 2, 1969.

©1969 Andrew Earl Barnes

Andrew Earl Barnes, Assistant City Editor of The Washington Post, is on leave for a year to study European cities as an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow.