Roxanne Scott

Freelance journalist

Rosedale, N.Y.

- 2024

Fellowship Title:

- After Decades of Disinvestment, Black Neighborhoods in NYC Feel the Brunt of the Climate Crisis

Fellowship Year:

- 2024

How Heavy Rains and High Tides Hurt Nyc’s Black and Brown Neighborhoods

Normally, Estefani Nuñez parks the small yellow school bus she drives each day by the side of her home in the Rosedale neighborhood in Queens. On the day before she knows it’s going to rain, she parks her school bus a block away. When it does rain, she puts on her tall black boots to wade through water to make sure the children she has to pick up get to school on time. Estefani Nuñez in front of her Rosedale home where she lives with her two children, elderly parents and husband. Nuñez says she experiences flooding from high tides and rainfall. Credit: Damaso Reyes Sometimes the boots aren’t enough and she is forced instead to wear garbage bags over them. Once in a while, when the water is too much, her own two kids become trapped at home because the flooding prevents them from leaving their house to make it to class. A sign on Brookville Boulevard, or Snake Road, and 149 Avenue in Rosedale, Queens warning drivers of potential flooding. Credit: Damaso Reyes

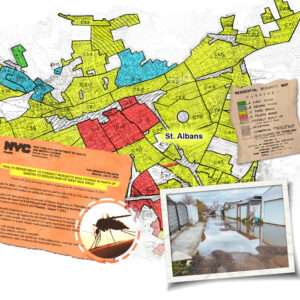

A climate change forecast: rain with a chance of mosquito-borne diseases

Decades before Elizabeth Blaney, now 84, moved to St. Albans, the neighborhood was shaded yellow on maps made by the federal government. The color yellow could mean there was a high number of immigrants—or that there was a possibility of Black people moving into the neighborhood. But being coded yellow also meant environmental threats existed. In St. Albans in the 1930s and ’40s, that meant being in low-lying land or having few to no sewers or poor transportation options. Blaney moved to St. Albans about three decades after those maps, made by a government agency called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, were created. She didn’t have a car in the suburban neighborhood, but she was able to walk her children to the nearby elementary school. She could also walk to the grocery store and church, and she formed relationships with neighbors she’s still friends with today. However, the aspects of the neighborhood that were first deemed detrimental by those federal maps—long before Blaney arrived—still persist. Today, St. Albans still sits in low-lying land. There are