Andrew Barnes

- 1969

Fellowship Title:

- Urban Problems in Europe

Fellowship Year:

- 1969

Paris in the Park

Paris, September 18, 1969 Molly Barnes Molly Barnes is the wife of Andrew Barnes, Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from the Washington Post. After hours of traveling in cramped spaces first priority in Paris was finding a park for the children. One look at that huge expanse of incredibly green, immaculately clipped lawn and our two small boys pounced on the grass. Guards began tweeting their whistles and waving their arms. People stared. Then I saw the sign: Pelouse Interdite – Forbidden Lawn, The children were puzzled at first but seemed to accept this new order of thing, this park deportment Paris style. Paris has hundreds of parks and squares. Gentle green oases in the gray of Paris have been created in the centers of traffic circles, around statues and fountains and as periphery to the grand public buildings. From plots no larger than a house lot to tracts of thousands of acres, Paris has made splendid parks. In a few of the city’s more crowded sections the most park one

Baron Haussmann”s Paris – II

March 7, 1970 It was just a century ago, in 1870, that Baron Georges Eugene Haussmann finished remaking Paris. He didn”t, himself, think the job was done, but he was fired. The imminent downfall of his political protector, Emperor Napoleon III, was one reason for Haussmann”s dismissal. Another was the legion of toes Haussmann had trod on while moving the city around for 17 years. His enemies finally became too numerous. Haussmann”s burst of innovation had been over for several years anyway, and the odds and ends were tidied up by succeeding city administrations. In fact, that is a great deal of what succeeding city administrations have done – finish up what Haussmann laid out. Paris, of course, is a glorious city. It seems presumptuous even to say it. Paris is also a fairly efficient city. For most of the years since Haussmann city governments have been able to decide their problems were not too pressing. And yet, there has been about Paris a certain sense that the city used to be even better.

Baron Haussmann’s Paris – I

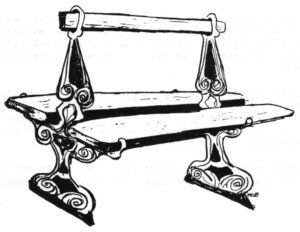

Paris, Feb. 8, 1970 When Georges Eugene Haussmann was put in charge of Paris, he planted his feet, took hold of the city, and shook it. He kept up this approach to running the city for 17 years. When he was through, there was little of Paris that hadn’t been rebuilt, or torn down, or both. Just a century has passed since Haussmann was fired. Paris is still his. Not everything, to be sure. The Metro and the Eiffel Tower are since his day, and perhaps a few other things. But Champs Elysees, Etoile, Opera, Boulevard St. Michel – all the famous boulevards of Paris are Haussmann’s. The sewers are his. The water is, too. (Yes, the water is safe to drink. It also tastes all right.) The Louvre was finally finished by Haussmann. The Bois de Boulogne was built by Haussmann. Longchamps is Haussmann’s work. So is almost every other Paris park. Even now, more Paris houses were built by Haussmann than by anybody else. Les Halles, for a thousand years the central

A Sofia Postscript

Paris, Dec. 28, 1969 Each time I had the chance in Sofia I tried to find out where and from whom the city professionals, especially planners, were learning what to do and how to do it. Sofia seemed (and seems) a city happening late – in some respects facing now the problems of London in the 19th century, Moscow several decades ago. With Sofia’s planners, theoretically, in a position to shape developments that were private business in London, perhaps less clearly understood when they appeared in Moscow than they are now, Sofia seemed possibly the place of places where repetition of the mistakes of others could be avoided. Such comparisons are far too facile, and have as much wrong about them as right. The question “How are you avoiding other cities’ mistakes?” remains a useful one, nevertheless. Kourdalanov, the engineer from the department of progress at the Construction Ministry, at least seemed to understand the question. (He was the man who had spoken of Le Corbusier and parking problems, both pretty foreign to Sofia,

A City’s Style

Rouen – William the Conqueror returned to Rouen to die. Joan of Arc was condemned and burned here. Along the medieval twisting of its cobbled streets, Rouen looks very much a part of its past. The harbor, too, is still the junction of Seine River barges and ocean freighters, as it has been for ten centuries. Great cranes now fill the skyline before the city’s steeples, but the mind’s eye fills in masts and spars. Rouen has always changed. Change is written in the variety of the city’s facades. Now, like all the cities of France, it must change still faster. There are many more people and many more stores. The demand is for kitchens and toilets and cars, and somehow the city must supply them. Also, Rouen was bombed. In 1940 and again in 1944, 225 acres of the city’s heart were leveled. This piece, mostly pictures, is about what change does to a city’s style. Downtown Rouen wears its past proudly. Rouen has made some of the same obvious mistakes as every place.