Blaine Harden

- 1993

Fellowship Title:

- The Columbia River

Fellowship Year:

- 1993

Slackwater

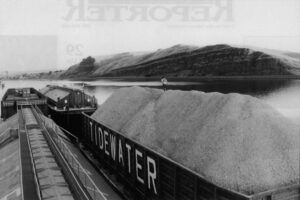

Photos and article by APF Fellow Blaine Harden LEWISTON, Idaho — We sailed west at sunset on water the color of dark chocolate. The sun disappeared slowly into the downstream distance, notching itself between knobby, bald hills and burning out in a long tomato-red smear. The river smelled of the farms it irrigates and erodes, a swampy perfume of mud and fertilizer, algae and a hint of dead fish. A barge in the Snake River, near Lewiston, Idaho. Down in the galley, groggy from afternoon naps, a fat tugboat skipper and a muscular deckhand were playing a quick hand of blackjack, yawning, smoking, drinking coffee, scratching themselves in manly places, and preparing for a six-hour shift of squiring twelve-thousand tons of peas, lentils, wheat, computer games, wood chips, and polyurethane-coated milk cartons out of the hinterlands of the West and off to the consuming capitalists of the Pacific Rim. On the splendid September evening that we lumbered out into the middle of the Snake River, the principal tributary of the Columbia, the tugboat Outlaw

Saved by the River

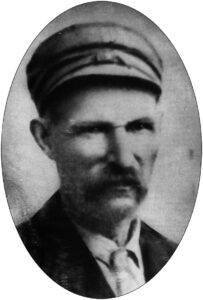

Arno Harden sneaked aboard a boxcar in Great Falls, Montana, in the late summer of 1932. He was twenty-one, fresh out of work, alone, and heading West. Everything he owned he carried with him. He had a bedroll and a pillowcase half-stuffed with clothes and one pair of shoes, the work boots on his feet. He wore a plaid wool mackinaw and a black cap with flannel earflaps. Two months of bucking hay for a Great Falls farmer who let him sleep in the granary had earned him $80. The money was in his pocket, along with a sandwich he bought in a rail-yard cafe. My father also carried a letter — from his father. Elvin Eldorado Harden, the author’s great-grandfather. The letter told him not to come home. It said there was nothing at the family farm in northeast Montana to come home for. His mother had died in the spring, of liver cancer at the age of forty. Drought had ruined the three-hundred and sixty-acre farm that his father leased from a New

Bad Comedy at America’s Biggest Environmental Mess

HANFORD, Washington — The mulberries happened to be ripe. They caught the eye of a hell-raising physicist by the name of Norm Buske. He picked a quart and rushed home to make what turned out to be high-anxiety jam. The berries grew here along the banks of the Columbia River, where it arcs across a sagebrush desert in southeast Washington State. The river borders the Hanford Site, America’s largest and leakiest repository of nuclear waste. After Buske made his jam, which was radioactive, he mailed it to the governor of the state of Washington and to the secretary of energy in 1990. Norm Buske takes a sample of Columbia River water, which was tested for radioactivity. When Buske made “hot” jam from mulberries growing along the river, the publicity prompted the government to hack down berry bushes and bury the branches. (Photo courtesy of Norm Buske) So it was that two jars of ruby-red preserves gave birth to the mulberry syndrome. Within hours, emergency mitigation began. Hanford workers, wearing blazing white radiation suits and wielding

The Grand Coulee: Savior for Whites, Disaster for Indians

COULEE DAM, WASHINGTON – Halfway across a narrow steel bridge over America’s most powerful river, a sign announces the entrance to the Colville Indian Reservation. The sign is small and easily missed in the vast gorge that cradles the roiling Columbia River. The modest sign poses a question whose answer may come to rattle the most profitable pillar of the federal government’s public-works empire in the West. A Colville Indian chief stands with government engineers on March 22, 1941 as the switch is turned at the opening of the Grand Coulee Dam. Department of the Interior U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Grand Coulee Project Looking just upstream from the steel bridge, the question becomes obvious. For there is the greasy-grey concrete monstrousness of Grand Coulee Dam. It is the largest producer of electricity in the United States, a half-century-old totem of American engineering virtuosity, and the economic cornerstone for nine million people in the Pacific Northwest. “The mightiest thing ever built by a man,” sang Woody Guthrie, the folk balladeer whom the federal government hired in