Brian Donovan

- 1981

Fellowship Title:

- U.S. Petroleum Policies

Fellowship Year:

- 1981

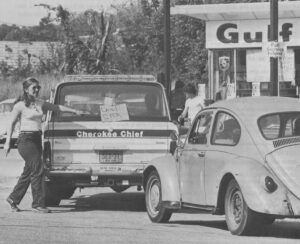

Cutting Back

WASHINGTON, DC–While motorists waited in lines during the 1979 oil crisis, Mobil and Gulf made sharp cuts in gasoline allocations that were not consistent with their ample stocks of gasoline and crude oil, an unpublished government study shows. Department of Energy officials used a computer to analyze confidential company supply data and found that although Mobil and Gulf were not short of oil, they imposed gasoline allocation cutbacks similar to those of companies that were suffering shortages. The study adds new information to the controversy over oil companies’ role in the crisis, which started with a temporary halt in Iranian oil exports and resulted in a doubling of world oil prices. Although the study does not impute motives to the companies, its findings add support to the arguments of critics who contend that industry actions during the crisis helped prolong the market panic that encouraged the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to keep raising its prices. Gulf and Mobil spokesmen criticized the study, calling it misleading. “It rehashes an old and discredited allegation that

The Real Price of Oil

WASHINGTON, DC–John O’Leary has spent most of his adult life grappling with one tentacle or another of America’s energy problem. Generally he’s been armed with an impressive title. His resume lists a long string of high-level government energy posts. At various times he has been a top regulator of natural gas, coal, nuclear power and oil. He runs a successful energy consulting firm. He speaks with first-name familiarity of his contacts in world finance and various governments. As a well-off Washington insider of 55, O’Leary would seem to have reached a career peak from which he could look back upon a distinguished past and ahead to a comfortable future. John O’Leary, Deputy Energy Secretary under President Carter. WIDE WORLD PHOTO Actually, as O’Leary tells it, he takes little pleasure in looking either forward or back. As deputy energy secretary under President Carter, O’Leary played a central role in the government’s efforts to deal with the oil crisis of 1979, an event whose effects, he says, are still devastating the American economy. When O’Leary looks back,

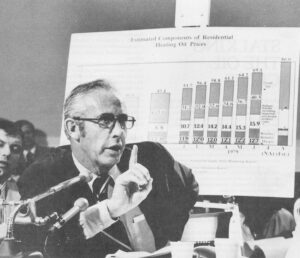

Stalking The Oil Crisis

WASHINGTON, DC–To motorists lined up at the pumps, the crisis of 1979 was easy enough to define: a gasoline shortage and soaring prices. But during most of the year, top officials in the White House and the Department of Energy devoted much of their efforts to managing another crisis–one that never happened. In preparing for this phantom crisis, these officials were doing something that, at first glance, seemed eminently reasonable. The limited data available to the government showed unusually low heating oil stockpiles in the spring of 1979, and officials feared that a heating oil shortage could strike the next winter unless stocks were built up substantially. They felt that heating oil for the winter was more important than gasoline in the summer, and they adopted policies and carried out programs that deliberately favored heating oil production at the expense of gasoline supplies. When all the concern over heating oil proved to have been unnecessary–the winter brought a glut of it, not a shortage–DOE officials defended their policy as a prudent, sensible response to an

Oilspeak

WASHINGTON, DC–While the Reagan administration’s deregulation blitz continues, a paradox has emerged on the question of how the U.S. government will handle the next oil crisis. As things stand now, two seemingly contradictory strategies are in place. Predictably enough, the administration is planning a purely free market, hands-off approach to the issue of how oil products will be distributed within the U.S. during a crisis. A recent policy paper says that domestic petroleum prices will be allowed to rise to whatever the traffic will bear during a crisis, and consumers’ ability to pay the higher prices will be the only thing that determines who gets how much gasoline and heating oil. But at the same time, the administration has announced its support for an international organization whose main feature is a cumbersome and uncertain regulatory scheme to control the international oil market during a severe crisis. This plan, the emergency oil sharing plan of the International Energy Agency (IEA), is replete with complicated regulations, government intervention, constraints on companies’ actions–just about everything, in other words,

Blackouts: Eclipsing Energy Information

WASHINGTON, D.C.–As the country struggles with the energy dilemma, something vital to the task keeps getting stolen: information. The culprit is the executive branch of the federal government, which for the past several years has repeatedly acted as a censor and crude propagandist in energy matters. Recent energy history is littered with examples of shaky guesses presented as facts, apparent scare tactics, attempts at juggling facts to justify predetermined policy, and efforts to squelch government studies that raise questions about policies. A clear pattern of this sort ran through the Carter administration and similar incidents have begun surfacing under President Reagan. In theory, everybody agrees that energy information is important. The country is making choices that will determine the desirability of America as a place to live. Some of the choices are Faustian bargains with danger and pollution, such as deciding how many nuclear reactors and how much coal we will need to keep the economy working. Without a free flow of energy information, without an atmosphere in government that encourages honest fact-finding, we would