Charlise Lyles

- 1990

Fellowship Title:

- A Better Chance: A Unique Educational Experiment

Fellowship Year:

- 1990

Opportunity’s Dance with One North Carolina Family

It was 1968. Arnetra Johnson, a black woman raising four bright-eyed babies alone in a rural North Carolina trailer park, was holding fast to the dream just as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had laid it out: black boys and white boys sitting side by side in the same classroom. She agreed: one day her children would attend the great integrated schools up north, far from the unenlightened, still segregated south. Didn’t her youngsters deserve the finest institutions America had to offer? She listened closely for whispers, rumors, promises of opportunity that some said would come flowing from the blood of Dr. King and others who fell for civil rights. Church sermons prophesied it. Newspapers reported programs, acts of Congress. Then came tire letter from her well-educated brother-in-law in Atlanta. He had heard about a special program that sent smart black boys and girls like hers away to private schools-,’the best in the country,” he wrote: For free. The program was called A Better Chance, Inc. (ABC). It was the benevolent brainchild of a visionary

Help for Strangers in a Strange Land

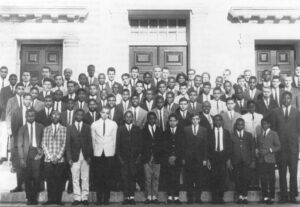

In an upcoming NBC television movie, a black youth from Harlem graduates from Phillips Exeter Academy with honors. Three weeks later, he is shot to death by an undercover police officer who alleges the young man tried to rob him. The film is based loosely on the life of Edmund Evans Perry, one of hundreds of disadvantaged minority youths who have attended preparatory schools through the national minority talent search agency, A Better Chance, Inc.(ABC). Another theatrical account based on Perry’s life is “No Laughing Matter,” an upbeat amateur musical performed before ABC students currently enrolled in prep schools. But this version has a happy ending. In it, a black youth from inner city America triumphs over the angst, insecurity and ostracism of going to boarding school and returning home. The Bronx-based Positive Youth Troupe performs “No Laughing Matter” before a gathering of black prep school students at the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut. (Photo by Charlise Lyles.) Both pieces mirror the real pressures ABC students face. Many find themselves straddling two worlds, galaxies apart:

Importing Girls to Integrate a Connecticut Public School

Ridgefield, CT-The cute Puerto Rican girl from the Bronx perched atop her bunk bed in a boarding house and pondered her ambivalence toward this affluent, mostly white town where she attends school. Ana Negron, 17, delighted in the academically challenging school. She adored the local host family that welcomes her on weekends. She abhorred the prank telephone callers who nearly four years ago threatened: “All “n…..”s die.” Students and tutors at the Ridgefield ABC house included, (left to right) Debby Lashley, Simone Page-Janello, Ana Negron (seated), Steve Blumenthal, Karen Schwamb (standing), a former tutor, Carlina Santos (seated), Shauna Daniel. (Photo courtesy of The Ridgefield Press.) “When I first came here for some reason, I didn’t really notice that everyone is white,” said Negron, who hopes going to Ridgefield High will help fulfill her dream to become a psychologist. “I guess I saw coming here as an academic opportunity to go to a better high school and to get into a good college so that’s all I was thinking about.” “But we’ve had really bad experiences,

Clearing a Path from the Ghetto to Choate

In Judith Berry Griffin’s office on Boston Common, a watercolor called The People Could Fly hangs on the wall. It portrays blacks of every age and size taking to the sky like birds. As president of ABC: A Better Chance, Inc., Griffin’s job is equally ambitious–to help minority children soar into high achievers at the nation’s premier college preparatory schools. Each year, her corporation places more than 300 inner city youths in private schools that are willing to subsidize black academic promise to the tune of $12 million in scholarships. “We play a critical role in these children’s lives,” said Griffin, her dark eyes shining. “Every child, if he wants to live fully in America, has to step into the mainstream. Our goal is to help him jump into the river and get to the other side as quickly as he can.” But she and others who have sat behind her desk have been accused of perpetrating a brain drain and other offenses on the black community, sometimes by the very students ABC sought to