Donna DeCesare

- 1997

Fellowship Title:

- Youth Identity and Gang Violence in the Americas

Fellowship Year:

- 1997

![At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ. looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side [of the bars]. “Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.”](https://aliciapatterson.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DeCesare_Haiti01-300x204.jpg)

Haiti: Giving Hope a Second Chance

“You’d always know in the pen when somebody got the L note [A life sentence]. It’s the one time a man can cry in prison. Being sent back to Haiti…it’s like being buried alive.” Touchè Caman, U.S. deportee and organizer for Chans Altenativ Port-au-Prince, Haiti—On the second day of his homecoming—after living eleven years in the United States—twenty-two-year old Patrick Etienne is overcome with emotion. The silent rivulets streaking his cheeks and staining his pristine white tee shirt are not tears of joy. Along with 36 other criminal deportees, he was escorted by U.S. Federal Marshals onto a special plane and released into the hands of CIMO, the paramilitary anti-riot squad of the Haitian National Police. Patrick doesn’t yell—as several of his cell mates do—about his rights or the unsanitary and primitive toilet facilities here at the Haitian National Penitentiary where the group are being held. “Just wait till they get outside,” he utters in a barely audible whisper As Patrick describes the incident that has landed him back in Haiti—injury he caused another motorist

Struggling to Change in Spite of the Odds

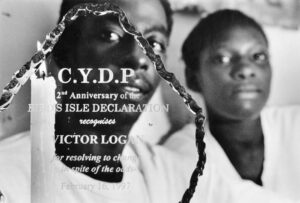

Belize City, Belize–”Stinga,” is a Conscious Youth success story. The former head of the Black Scorpion Posse, BSP, is one of the original gang leaders, who signed a historic truce halting gun battles on Belize City streets. Stinga surveys his muddy surroundings before venturing from the water-logged cubbyhole where he lives with his 17-year-old girlfriend Candace. He is one of the few peacemakers who is not dead, currently in prison or once again an active gang member. Stinga owes his survival not only to his precaution, but to participation in the Conscious Youth Development Program, a government effort to rehabilitate gang members. Victor Logan, “Stinga” displays an award recognizing his efforts to uphold the 1995 gang truce and to better himself through the Conscious Youth Development Program. It reads: CYDP 2nd Aniversary of the Bird’s Isle Declaration recognizes Victor Logan for resolving to change in spite of the odds. February 16, 1997. Photo by Donna DeCesare Despite his success, Stinga’s environment is closer to early 60s Mississippi delta than the Belizean paradise islands and rain

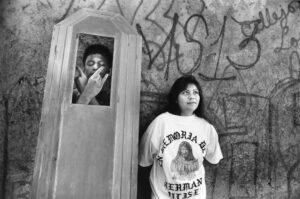

Avenging Angels: Homegirl Survival Stories

Text and photos by Donna DeCesare “The weak one is the one society thinks is good, but that’s the one that is going to end up dead.” –Angel, Latina gang member “Trippy” from Mara Salvatrucha getting a new tattoo. Photo by APF Fellow Donna Decesare Los Angeles — “Call me Angel,” she said evenly, meeting my gaze. A faint scent of wet Pampers clings to her knit top after she places her toddler, Tonio, in blankets on the floor. Sinking heavily into a black Naugahyde couch, she begins. “It was supposed to be a kickback for us homegirls, a slumber party.” I watch her “fangs” — those gravity-defying teased bangs favored by Latinas of a certain age — casting bird nest shadows on the mildew-stained wall as she speaks. Angel remembers waiting at the house with Dreamer while the other homegirls made a beer run. “There was a knock at the door. I got up thinking — ‘gotta be the homegirls,’ but before I know what’s up, my best friend Dreamer is yelling at me:

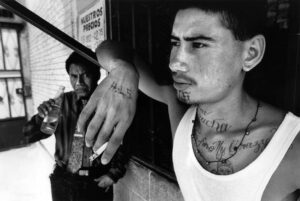

How Edgar Bolaños Became Shy Boy in El Salvador

Text and photos by Donna DeCesare Soyapango, El Salvador — During pre-dusk hours when school children in crumpled uniforms race home, past the maquila factory workers wearily descending from buses, Shy Boy and his friends emerge alert and ready for business. They scatter in clusters around their cul-de-sac. Several move towards a grocery store, displaying their crop of gold chains and other “hot” items for interested buyers A middle-aged woman, with stern Indian features, balances a basket of fruit on her head as she glides past graffiti-sprayed walls. Three not-so-muscular youths in tight muscle shirts wave their tattooed arms wildly, throwing gang hand signs and flirting to grab her attention. Finally, she cracks a smile. Wiping her hands on her stained, ruffled apron, she lowers her basket. The boys laugh as mango juice escapes from their lips. She laughs with them. Shy Boy, aloof and elusive, takes in the scene. “People here think I’m the gang leader because I used to live in Los Angeles,” he says, almost wistfully. “But we don’t have leaders. I