Dorothea Jackson

- 1991

Fellowship Title:

- Economic Survival in the Southern Highlands

Fellowship Year:

- 1991

Staying in the Southern Highlands Against the Odds

Photos and article by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson There is a flat room-sized rock that sticks out into a pool in Big Santeetlah Creek, which borders Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest in Graham County, N.C. The place is called Rattler’s Ford, a name that more likely came down from a Cherokee family that lived here than from a snake. The Snowbird Reservation, a collection of Cherokee properties with disjointed boundaries, no commercial district and a largely Cherokee-speaking, history-conscious populace, is close by. In the summer, pickups jammed and rocking with young Cherokees disgorge in the parking area near the creek. The revelers hit the ground running for the rock; it is their jump-off place into this pristine and mysterious stream. Not one bit does the legend of nocturnal business here dampen these festivities. If (as some witnesses declare) ghostly warriors still come shouting, crashing through the night woods and splashing through this icy current, if indeed the sweaty-smelling spirits do surround and swarm upon this rock in pursuit of ancient enemies, no one begrudges them their

The Ways and Means of Holding on in the Highlands

If one only had an aviator cap of thin, fine leather, with earflaps and a chin strap that one snapped in a gesture of importance while settling into the feed trough, er, cockpit, one could shout, “Contack!” (an important aviator word) with a tone of authority. And with a deep-breathed HrrrrRRRMMMM! the propeller would whirr. And one would be lifted, transported on silvery wings, over the barn lot, the pasture, the summit of Mt. Mitchell and uncharted lands and seas beyond. But one had to have an aviator cap. Floyd Wilson was a little boy in Yancey County, N.C. in the era of bi-planes and barnstormers. He was born in 1918, the year the war to end all wars came to a close and the flying aces came home. Their stories were the new stuff of heroism and adventure. Worn-out tales of barehand fights with bears and wildcats paled beside accounts of dogfights with the Red Baron. Every kid in America wanted an aviator cap. Floyd Wilson set out to get one. Floyd Wilson, a

Living at Home: Money and Migration

Photos and text by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson The Old South Carolina highway that snaked through the first wave of the Blue Ridge Mountains ends now in Lake Keowee. Literally, just short of where a covered bridge used to span the formidable green torrent that was Keowee River, the crumbled blacktop now descends into depths of aquamarine. As the farms and timberlands were being leveled in the 1960s for the two-dam Keowee-Toxaway hydroelectric project, a new Scenic Highway 11 was built three miles south. For a long time, then, after Duke Power Company closed the floodgates on the river in 1968, and after traffic began to cruise smoothly over the long new concrete bridge and speed-tolerant new road, far back in the woods one could walk the old road’s yellow center line out into the clear lake water, deeper and deeper. The view near the top of the Appalachian range at Craggy Gardens, on the Blue Ridge Parkway near Asheville. Mist and clouds brush the mountain tops after a spring rain. The rhododendron gardens are

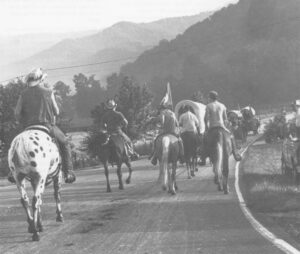

How It Was: The Bedrock of the Appalachian Dilemma

Photos and Article by APF Fellow Dorothea Jackson. It is spring and along the Daniel Boone Parkway, between London and Hazard, Kentucky, yellow wildflowers bloom from the fractured stone faces of mountains that have been dynamited open for the passage of the road. From ditches kept watered by the seeping rocks, peep-frogs sing earth’s oldest, shrillest evensong to passing travelers. In an annual tribute to early settlement, a wagon train moves into Tatham Gap, outside Andrews, North Carolina. Some of the road ahead is dirt, though much improved since thousands of Cherokee Indians were herded along it in 1838, on the first 12 miles of the Trail of Tears. Beside small streams the willows come awake in neon green. Tiny cemeteries dot still-bare woods on the hillsides, bright with those botanical wonders known to florists as “permanent arrangements.” Under these memorial sprays of wilt-proof pinks and lavenders and reds lie two centuries of stories of what it took to get into this hard, high land, and what it took to stay. Here, the influx through