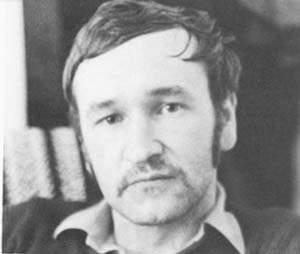

John Conroy

- 1980

Fellowship Title:

- Social and Economic Consequences of the War in Northern Ireland

Fellowship Year:

- 1980

Crazy Joe’s School

BELFAST–Just on the edge of downtown Belfast is a public housing project, populated entirely by Catholics, called Divis Flats. Though the flats were built less than 15 years ago, the site is now a slum. Rats run on balconies late at night, and are hunted for sport by dogs and children. Soldiers long ago put out the lights in some passageways because they made the troops better targets, and people occasionally defecate in the dark stairwells. The residents are looked down upon, even by their own kind from up the road, as a lower form of humanity. They are also looked down upon by the army, which has an observation post on top of Divis Tower, 20 stories above the ground. In the lower depths of one block of flats is a set of garages. One of the garages was converted to a youth club years ago. At one point the club was run by one Joe Morgan, and it came to be known as Crazy Joe’s. Joe is now long gone, but the name

Jesus Christ and Jesse James in Belfast

BELFAST–On May 27,1980, in a suburb of Belfast, sixty outraged citizens paraded outside their town hall. When the councilmen of Newtonabbey arrived for their scheduled meeting, the demonstrators became impassioned, “Murderers, ” they yelled at their elected representatives, “murderers.” The picketers hoped to persuade their councilmen to deny Abbey Meats a license to carry out the ritual slaughter of bullocks. The meat company had received a 4 million pound contract to provide beef to Libya, and the contract required the company to slaughter the animals in the Islamic tradition. The procedure performed at Abbey Meats involved penning the castrated bull in a confined space, and while the animal was still fully conscious, raising its head and slitting its throat. The Belfast papers reported that an Arab had been brought to Northern Ireland specifically to oversee the task. Those who objected to the killing thought the method was too brutal, that the animal should have been stunned first. At the council meeting attended by the demonstrators, the town fathers decided to grant Abbey Meats the required

The Wall

(BELFAST) – Cupar Street is a no man’s land. An administrator in the Department of the Environment recently referred to it as “the frontier,” as if it were a stretch of wilderness between two nations across which there were daring escapes. Other bureaucrats call it an “interface”. In fact it is just a street. The neighborhood to the south of it is a densely packed, working class Catholic district full of two-story brick houses built in the last century for linen mill workers. The neighborhood north of the street is not so dense and is populated by Protestants. Between the communities is a wall, commonly known as the peace line. The “peace line” on Cupar Street in Belfast separates Catholic and Protestant territory. The wall is made up of rows of derelict houses, all but three of them bricked shut, and sections of corrugated iron, 20 feet high, which stretch across avenues that once intersected Cupar Street. At the far end of the border, where Cupar Street curves into Catholic territory, the army has installed

Jimmy Barr, Squatter

(BELFAST) — Short guy, this Jimmy Barr. Thirty years old, cocky, given to drunkenness, he will go out of his way to irritate an enemy, and he has several thousand of them, all well armed and patrolling his neighborhood day and night. Unemployed, has been since 1969, probably will be in 1989, if he is still alive. Plays the horses, but not so well. When I first met him, he had a tip on Nameless Pixie, a hound running at Belfast’s Dunmore track, but Jimmy doesn’t bet on the dogs. Nameless Pixie paid three to one. Like thousands of Belfast men and boys, Jimmy has a tattoo. His right forearm is interrupted by a small blue heart with “MARIE” written inside. Marie is his wife, a pleasant lady with large blue eyes, near perfect teeth, and — very rare in Belfast — a trim figure. She grew up in a local housing project called Turf Lodge, worked for a short time as a stitcher at the Ladybird Shirt Factory when she left school, but abandoned

Kneecapping

(BELFAST) — “Sometimes people were beaten up first, and there were fractures underneath, so you had to be careful when you removed the tar, ” says Sister Kate O’Hanlon, the buxom and motherly head nurse at the emergency room of the Royal Victoria Hospital in West Belfast. “It wasn’t actually tar, it was thick diesel oil. The oil is not as bad as burning tar, but it all makes a real mess. You remove it with eucalyptus. The Supply Department said we were using more eucalyptus than anywhere else in the United Kingdom… Sometimes they threw paint on people instead of tar. We had to call the painting foreman in, he told us how to remove it. We use acetone. “I think they gave up tar and feathers because it made too much of a mess for the people who were doing it. Kneecapping is a cleaner job for them. “ Andy Tyrie, Fu Manchu moustache, heavy sideburns, stomach showing between button holes in his shirt, is head of the Ulster Defense Association (UDA), the