Marc Reisner

- 1979

Fellowship Title:

- Analysis of the Federal Government's Water Resources Policies

Fellowship Year:

- 1979

The Western Imagination

(CALIFORNIA) — A few months ago I flew over the state of Utah on my way back from Washington to San Francisco. It was a late night in November, and a fierce early blizzard had swept out of the Rocky Mountain States. I had an aisle seat, and since I believe that anyone who flies in air airplane and does not look out the window most of the time wastes his money, I went back to one of the doors adjoining the rear galley of the airplane, a DC-10, and stood there for a long time, lulled by the heavy drone of the engines, staring out the door’s tiny aperture. The frozen fire of a winter’s moon poured cold light on the desert below. Six inches away from the tip of my nose the temperature was minus sixty-five degrees, and seven miles below it was, according to the pilot, nine above zero, but here we were, two hundred highly inventive creatures safe and comfortable in a fat winged cylinder racing over the Great Basin of

Things Fall Apart

SAN FRANCISCO — The Colorado River rises high in the Rockies, near Long’s Peak in the state that bears its name, and begins its 1500-mile, 12,000 foot descent to the Gulf of California. Its waters are sweet. The Colorado’s volume swells quickly from snowmelt, and before long it is a roaring churning violently through red canyons down the long West Slope of the Rockies. Not far from the great Utah desert, near the town of Palisade, the rapids die into riffles and the tempestuous Colorado becomes, for the relatively short length of forty miles, calm and sedate. It has entered the Grand Valley, a small but productive agricultural basin full of orchards and grazing cows looking utterly out of place in a landscape where it appears to have rained once, about half a million years ago. Agriculture in the Grand Valley depends on the river, so a good deal of its water takes an excursion there to irrigate the fields. As the water leaves the river, its measured salinity content is about 200 parts per

The Straw in the Chocolate Malt

In Los Angeles they had the votes and in the Central Valley they had the money, and so, over the strenuous but hopeless opposition of most of northern California, the inefficient water system which God designed for California was replaced by a much more efficient one designed by man. The transformation was wrought mainly by two immense water projects: the Central Valley Project, which, though begun over forty years ago, is still the most awesome hydrological engineering works in the world; and, in the 1960s and 1970s, the California Water Project, the largest engineering and financing scheme ever attempted by a single state. Both projects bring water from behind reservoirs in northern California over mountains, through tunnels, and across deserts to the southland. They rank with the engineering wonders of the world. And yet, as engineering projects, they share a peculiar weakness, a design element almost astonishing in its careless inefficiency. On its way south, all of the water is flushed through the Delta. The Delta How many people, how many Californians even, have heard

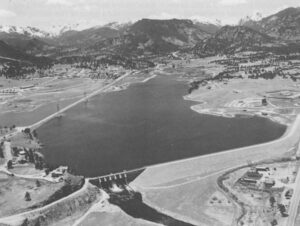

Water Wars in Colorado

(DENVER) – In early August, shortly after President Carter proposed his dramatic shift in U.S. energy policy-the federally subsidized production of millions of barrels of synthetic fuel per day from coal and oil shale-I was in Denver talking with people about water and how its relative availability or scarcity will affect the future of the arid Rocky Mountain and High Plains states. It is toward this region, of course, that the President’s new energy creation, in whatever form it appears after having been disassembled and rewired by Congress, will come lumbering, because most of the nation’s coal and nearly all of its high-grade oil shale lie roughly within a 600-mile oval in the states of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and Utah. My first interview was with Alan Merson, who had just resigned as regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. Merson, an amiable, intense man with a disarmingly candid manner, is a former law professor and occasional tester of political waters; he upset Congressman Wayne Aspinall in the Democratic primary of 1972, but lost in the

Bread Upon the California Waters

(SAN FRANCISCO) – Mark Dubois, chief friend and defender of the Stanislaus River, was wheeling the raft again. The racing water, the trees, the canyon walls, and the flecked sky whirred around in a languid blur. The universe was spinning and at the center was Mark, huge, bony, mostly naked, and grinning, each great paw gripping the handle of an out-sized oar, the arms penduluming mightily in opposite directions, making pirouettes in a sixteen-foot rubber Avon raft. Whitewater, Stanislaus River A roar announced another rapid. With the river swollen by snowmelt to 5,000 cubic feet per second, it would be big. We whirled around a bend. The river leaped and danced ahead. At the last second Mark straightened the raft and we plunged down a long series of four-foot rip waves. Sheets of icy water burst over the bow, tearing out my breath. I could sense a huge hole churning near the end of the rapid: water by the ton falling over a submerged boulder and crashing in upon itself with a frightful succckk! Mark