Mercedes de Uriarte

- 1982

Fellowship Title:

- Social Change in the U.S. and Central America

Fellowship Year:

- 1982

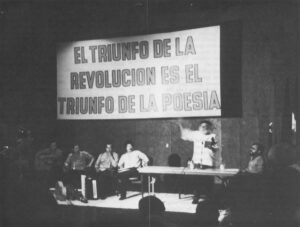

Nicaragua’s War of Words

MANAGUA–Nicaragua’s Foreign Ministry is housed in an expropriated neighborhood complex of former stores and boutiques. Its staff can often be found searching dog-eared book indexes to document upcoming diplomatic speeches. Computerized U.S. libraries could locate this information in minutes, but here it takes days–if indeed it can be found at all. Before fleeing the capital, President Anastacio Somoza’s troops destroyed books and vandalized state libraries. Shelves remain unstocked today even at the universities. Like any new kid on the block, post-revolutionary Nicaragua must find ways to negotiate with world powers while retaining its base of support at home. On the international playing field, communications is the first line of defense. Modern diplomacy is increasingly a matter of how skillfully a nation can communicate, but the Third World argues that it is unable to speak for itself and–like minority communities in the U.S.–loses by default. As contestants, Nicaragua and the U.S. are ill-matched–a flea against an elephant. The U.S. is a postindustrial giant which emphasizes personal computer purchases as a desirable middle class goal. It gathers

Political Deja Vu

MOCORON, Honduras–Here on the soft savannah plains and in the lush tropical forests, a story as old as the Spanish Conquest and as familiar as the United States role in the overthrow of the Guatemalan government and the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion unfolds. Miskito Indians, a small, indigenous group comprising less than 5 percent of Nicaragua’s population (less than 1/2 percent of Honduras), are trying to cling to a traditional way of life, even though they are now caught in the gunsights of political upheaval–pawns in an international conflict in which the U.S. plays an active role. U.S. involvement in the internal affairs of Latin American countries evokes a certain deja vu for Latinos in the U.S. It also highlights an uneasy schism within the U.S. between exiled upper middle class Latinos who are allied with fallen right-wing governments, and other U.S. Hispanics who sympathize with Latin Americans whom they believe are struggling legitimately against oppressive regimes. Some Cuban exiles in Miami who trained for the 1960 Bay of Pigs invasion are now helping

No Sense of Place

COLOMONCAGUA, Honduras–”We ran like animals,” said Claudia Garcia, 19, who, with her three-year-old daughter recently arrived at this sprawling refugee settlement housing more than 6,000 people. Claudia Garcia and her three-year-old daughter. Rica (Photo by Mercedes de Uriarte) In mid-May, her group of 46 campesinos left northern El Salvador fleeing a government offensive to drive guerrillas out of the area. For 22 days they trudged through soggy tropical forests, scrounging fruits and killing wildlife. Eventually the group grew to 200 people-men, women, children, grandparents-who moved toward the border, stopping to bury a young mother and her newborn child. The civil war in El Salvador is its single most important demographic catalyst since the Spanish Conquest. At least 200,000 Salvadorans are displaced; about 40,000 have died in the last three years; approximately half a million others-more than 10 percent of the population-are scattered from Canada to Panama. Almost all cross their city limits for the first time as they straggle reluctantly in an exodus to uncertain foreign hospitality. According to estimates from the United Nations High