Michael Millenson

- 1986

Fellowship Title:

- Deregulation of the American health-care system

Fellowship Year:

- 1986

Bottomline Medicine

The neighborhood surrounding Stony Island Avenue and 75th Street on Chicago’s South Side is middle-class to poor and mixes industry and stores on its main thoroughfares with homes and apartments on the side streets. On 75th Street just east of Stony Island, a bright blue awning stands out from a nondescript brick storefront. Neat white lettering advertises, “The Women’s Center.” Inside, amid soothing surroundings, a woman can talk about stress with a nurse, be examined by a gynecologist or get a mammogram to check for breast cancer. The center is owned by Jackson Park Hospital and Medical Center, whose buildings fill the rest of the block. The hospital decided recently that opening The Women’s Center was a good way to generate business since women traditionally visit doctors more than men and also make health care decisions for the whole family. In fact, a national survey of hospitals recently dubbed women’s centers “the” hot product line of 1986. “The center gives the idea, ‘This cares for you and your problems,’ ” explains Dr. Peter Friedell, president

Measuring Medicine

Several days a week, Dr. Harold Jensen pores through a stack of medical records from Ingalls Memorial Hospital, a 704-bed facility in a working-class Chicago suburb. Review nurses have used guidelines to winnow the patient charts down to those which may present problems. However, as part of the final peer review process by which physicians ultimately judge each other, it is Jensen’s job to decide what are allowable exceptions to the rules and what are medical errors. Though Jensen is an experienced reviewer, he readily acknowledges the difficulty of monitoring the 340 staff physicians who admit more than 20,000 patients annually. By necessity, only a limited number of medical charts can be reviewed in depth. With too much detail, he says, “you get swamped by the numbers.” That should change soon. Ingalls Memorial is installing a computer system that, for the first time, lets reviewers compare physicians to each other according to objective guidelines that measure just how well their patients are doing. The key to the new system is a method, still controversial, that

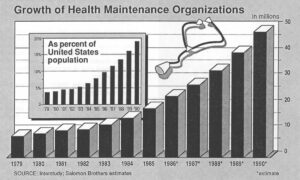

Managing Health Care

Elizabeth Olson thinks the day she joined the “Senior Care” program of Share-Minnesota was one of the luckiest of her life. She told her story in a full-page newspaper ad Share ran to recruit elderly members for the special Medicare version of its HMO. “In the past couple of years, I’ve had surgery, seen a lot of specialists and had months of chemotherapy. Share picked it all up,” says Olson of the Minneapolis-based health maintenance organization (HMO). She continues, “If they hadn’t paid for everything, I’d probably have a lien against my home. I would’ve been wiped out!” Mary Jane Bohnen has a different point of view. She told her tale in an investigative report broadcast by WCCOTV in Minneapolis. Her son, Daniel, had both eyes pierced by shotgun pellets in a hunting accident. Share paid for the first two operations, which unsuccessfully tried to save his left eye. On the day a crucial operation was set for the right eye, though, the Share business office called. Recalled Mrs. Bohnen, “(They) called me as I

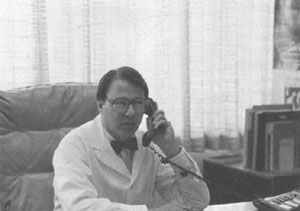

Reinventing Health Care

Every few months, Dr. Richard Bohannon watches in frustration as a 73-year-old woman he treats for chronic leukemia goes through a painful ritual. She arises early, drives 40 miles to San Francisco from her home across the bay, then spends the next nine hours in the hospital linked to an intravenous tube replenishing her worn-out blood with a fresh supply. When the tube is removed, she drives home. At one time, Bohannon hospitalized the woman the night before her transfusion. “She’s weak and frail. She tires easily. It’s hard for patients to go through that,” explains Bohannon, a specialist in blood disease and cancer and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Richard Bohannon But for almost two years now, Medicare has refused to pay for the hospitalization. Reviewers hired by the federal government say that the transfusion can be done just as safely, and much less expensively, on an outpatient basis. “It upsets me that my judgment isn’t more important than…some general rule,” Bohannon says. Still, his appeal