Miranda Spivack

- 2021

Fellowship Title:

- Expungement: A Public Good with a Dangerous Downside

Fellowship Year:

- 2021

Police Personnel Records Routinely Kept Secret, Erased. How That Hurts Accountability

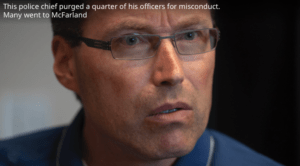

After four decades of hiding records of police misconduct, California has become one of the most transparent states. Prompted by a 2018 bill authored by State Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Berkeley Democrat, and two follow-up bills signed into law this year, the change means that it is much more difficult in California for bad cops to hide or get hired by another department. But across the nation, similar efforts to make police misconduct and complaint records available to the public — or even to police chiefs seeking to provide counseling or weed out bad officers — are moving slowly. In many states, not only can these records be kept secret, but they also can be destroyed or locked away indefinitely. Public pressure has increased to make the nation’s 18,000 police agencies more accountable to the public. But the secrecy of police personnel records, and the wide license that police agencies have to hide or get rid of the records, stand in the way. Often by contract and in some states by law, officers can prevent

States look to help people with criminal records find jobs, housing. What they’re doing

The clean slate movement to expunge public records of arrests and convictions has been gathering momentum as concerns about mass incarceration in the United States and the effort to decriminalize drug use have gained traction. But the potential erasure of these records has left some business owners and employers — who want to insulate themselves from legal risk and fear disruption from potentially troublesome tenants and workers — feeling anxious. ”We have enough challenges with people with no criminal record,” said Jeff March, CEO of BRG Realty Group in Cincinnati, Ohio, which owns rental apartments in Ohio, Indiana and Kentucky. While record erasure is available in nearly every state, it can be expensive and cumbersome. That has prompted several states to look at other ways to offset the consequences of having a criminal record, including offering certificates of rehabilitation to ensure good behavior and providing tax credits for employers who hire people with records. In addition, some states are looking at reducing or eliminating the fees that people on parole have to pay and boosting

Can ‘clean slate’ laws really erase criminal records from public view? It’s complicated

Anyone who has used a dating app knows the value of an Internet search before showing up for coffee. So do employers and landlords, who will scroll on their own for insights and information they may have missed in an interview, or that a formal background checker did not include. Online searches can turn up hidden work history, criminal records, and credit history, information that the prospective employee or tenant may not always offer up, nor be required by law to provide. But what would happen if the U.S. follows Europe and enacts “Right to be Forgotten” and other record-expungement laws, allowing individuals to get their Internet profiles scrubbed of negative information? Yet can anyone really get rid of records in the digital age? Online databases and searches have grown so large and unwieldy, many experts are skeptical that a person’s past can ever really be forgotten. Those who support the growing movement in the U.S. to give people with criminal records a second chance and the opportunity to re-enter society say it is imperative

‘Clean slate’ laws would erase criminal records. Do they make America more equitable?

‘Clean slate’ laws in America How effective are new laws that erase criminal records? Take a look at the racial justice movement taking hold across California and the U.S. that aims to allow former felons to find a better life. Timothy Poole has been out of prison — and out of the drug dealing business — for more than 20 years. In Sacramento, he is well known for his efforts to quell gun violence and for his visits with families of victims of violence. He heads his own nonprofit, Hooked on Fishing not on Violence, for years teaching kids how to fish in local rivers as a way of staying out of trouble. But when Poole wanted to bring his message of peace and hope into classrooms in the Sacramento public schools as a volunteer, he worried he would hit a wall. As is the case in many school systems across the country, people with felony records are frequently barred from employment and unpaid volunteer work. After more than 20 years of leading a crime-free