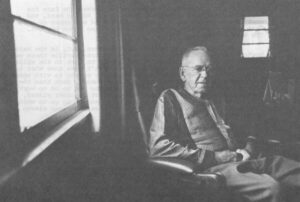

Richard Pearce

- 1975

Fellowship Title:

- The American Industrial Revolution: Textile Milltown

Fellowship Year:

- 1975

Graniteville, a Belated Introduction

Start from the river at Augusta, the Savannah with its slow churning delta batter of tidewater mud and mosquito larvae, and cross it into South Carolina. You’ll find yourself at the mouth of a small creek that for twelve miles has cut a deep valley into the surrounding Appalachian plateau. Horse Creek Valley or simply the Valley as it’s known to its more than 20,000 inhabitants is, like the Merrimack Valley in New England, one of this country’s early industrial cradles, spawning grounds for a new system of production that was by the turn of the century to have transformed and shaped an entire nation. Near the mouth of Horse Creek, quietly secluded among the blue granite hills which are its namesake, lies a town called Graniteville, presiding like some ancient tribal patriarch over the industrial watershed below. Historians may quarrel about whether Graniteville’s longstanding reputation as the South’s “first great cotton mill” is entirely deserved, but nobody since its inception in 1845 has disputed the fact that this tiny isolated community of one hundred

An Agreed-upon Tale of Two Families

“It was gravely stated to them…that they were all, when they arrived at the cotton mill, to be transformed into ladies and gentlemen; that they would be fed on roast beef and plum pudding, be allowed to ride their master’s horses, and have silver watches and plenty of cash in their pockets.” — (Paul Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, p.411) I) England 1760-1815. First there were the pauper children. “Indentured parish apprentices” they were called, indentured from as early as five years old, sometimes even four, until the age of twenty-one. In lots of fifty to a hundred like cattle they were negotiated from the quaint picturesque Dickensian workhouses of 18th century London to the remote factory towns of the north of England, where they disappeared from the public record. As Paul Mantoux, one of the early scholars of the industrial revolution, has put it, “The only extenuating circumstances in the painful events which we have now to recount as shortly as we can, was that forced child labour was no

Manufacturing Princes

“The real ruling class could not be put in question, so they were seen as temporarily absent, or as the good old people succeeded by the bad new people — themselves succeeding themselves. We have heard this sad song for many centuries now, a seductive song, turning protest into retrospect, until we die of time.” — Raymond Williams, The Country and the City, 1970. “Happily for me, my two eldest sons have turned their attentions in this direction, and I feel that the foundations I have laid in that line of business will now grow until a mighty structure is reared, and then we may look for Manufacturing Princes among us such as they have in England…James has given a new impetus and I now feel that in my failing years, the business which I have reared will go on with renewed vigor.” — William Gregg in a letter to James H, Hammond on Jan. 7, 1859. James J, Gregg, the son of William Gregg the founder of Graniteville, was eleven years old when he

Mister Prince Albert and the Healing Spring

“The employment of the white labor, which is now to a great extent contending with absolute want, will enable this part of our population in a very short time to surround themselves with comforts which poverty now places beyond their reach. The active industry of a father, the careful housewifery of the mother, and the daily cash earnings of four or five children will very soon enable each family to own a servant; thus increasing the demand for this species of property to an immense extent. This will be found to be the case in all those new villages which may spring up upon our rivers and streams under the vivifying influence of factory establishments. And it is as a pioneer in this great work that Graniteville is looked upon with deep interest.” — James Taylor, one of the founding directors of Graniteville, in De Bow’s Review, 1850. Ollie Whittle’s face breaks into a laugh like a set of china dropped from a second floor window. She leans forward in her green porch rocker with

Leisure Years

“It is only necessary to build a manufacturing village of shanties, in a healthy location in any part of the State, to have crowds of these poor people around you, seeking employment at half the compensation given to operatives at the North…who, if too lazy to work themselves, might be induced to place their children in a situation in which they would be educated and reared in industrious habits.” — William Gregg, Essays on Domestic Industry (1845) “The village had been laid out in broad streets and large squares; and upon these neat, uniform cottages were built which, with a large lot of land to each, were offered at a very low rent to those who would bring in their families and place them in the mill. “The plan worked well. The houses were soon filled with respectable tenants who paid a fair interest on this part of the capital; and, while the sons and daughters worked in the mill, the father would engage in cultivating his land, hauling wood, etc, and the mother would