Steve Bogira

- 1993

Fellowship Title:

- Urban Felony Courts and the Poor

Fellowship Year:

- 1993

Getting Caught Up: Families Pay The Price

CHICAGO–“Oh, he’s a nice-looking young man,” Rose Doyle said softly, of the tall, muscular 24-year-old in jail togs who was being escorted into the courtroom by a sheriff’s deputy. The man was Deron Jones. On the night of March 4, 1993, he pumped several bullets into a dark gangway on Chicago’s south side, in which stood the 43-year-old Doyle, her 34-year-old niece, Denise Turner, and her great-niece–six-year-old Delenna Williams. Delenna was struck in the chest and the wrist, and another bullet grazed her forehead, but she recovered. As Jones was ushered into the courtroom, Delenna was napping against Doyle’s shoulder, on the front bench of the spectators’ gallery. Doyle’s remark about Jones was directed at the women on the bench behind her–Jones’s mother, aunt, and girlfriend. “Don’t feel bad,” Doyle reassured them. “I got a big one just like him.” (Her oldest son has had his own troubles with the law.) Denise Turner, 34 and her niece, Delenna Williams, and nephew, Derrick Williams. The two children were disfigured in a fire that killed their mother.

Using Your Rights Means Extra Years in Prison

Vincent Boggan is among the few inmates in the Pontiac Correctional Center–a maximum-security prison in Pontiac, Illinois–who avail themselves of the free classes offered. He has already earned an “Associate of Applied Science”–a vocational degree–and now is working on an “Associate in General Studies”–a college-level certificate transferable towards a Bachelor’s degree. The degrees probably won’t ever win him a job, but “they’re doing a lot for me personally, ’cause I feel I’m accomplishing something,” Boggan, 27, said. “If you’re going to be down here, I feel like, school is free–take advantage of it.” Boggan found that exercising his right to a jury tial resulted in years more imprisonment than most of his fellow inmates who committed crimes where victims were injured or killed. He is scheduled to remain in Illinois prisons until 2025. Photo by John Sundlof If the courses of study were offered and Boggan were up to the task, he could earn several Ph.D.’s in the time he has here. His release date is October 21, 2025–when Boggan will be a half-year shy

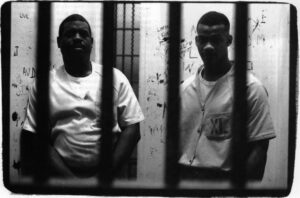

Pushing Treatment For Prisoners

CHICAGO–A tale of two junkies: Dwight Walker sat in his cell in the Cook County Jail last September, aching, cramping, and spitting up, and worrying about how much time he’d get for his robberies. Two inmates enrolled in drug treatment in Chicago’s Cook County jail await a court appearance. Photo by John Sundlof Walker, 27, craved heroin–as he has most of the time since he first snorted it, at age 20. He longed for a hit of cocaine, or at least a pint of wine. His addictions had landed him here, and now he was paying double. Walker had bought his dope with money he got from selling gold chains to a jewelry store in the slum he lives in, on Chicago’s west side. He and a friend would get the chains by snatching them off necks. “We’d get a chain and drop it [sell it]–get 40, 50 or $60–go spend it on half-and-half–coke and dope [heroin]. Go right back out, take more jewelry, go and drop it, get half-and-half, coke and dope. We’d do

Jailing Juveniles

A spirit of optimism about children created the nation’s first juvenile court, in Cook County, Illinois, in 1899. Kids who got in trouble were still kids, the prevailing thinking went, and the focus ought to be on reforming instead of punishing them. A metal detector is used in Mather High School in Chicago to find weapons that students carry. © 1993, John Sundlof, all right reserved. Youths who seemed beyond rehabilitation could still be tried as adults in Illinois, as long as they were at least 13. Habitual offenders, and those who committed particularly heinous crimes, were transferred to adult court on the petition of the state and a juvenile court judge’s okay. Such transfers occurred rarely, in keeping with the philosophy that those younger than 17 were amenable to change, and ought not, in most cases, be treated like adults. But the emphasis in Illinois has changed in the last dozen years, from reforming juvenile delinquents to convicting them. Legislators have passed a series of laws since 1982 requiring 15- and 16-year-olds charged with