Tamar Jacoby

- 1990

Fellowship Title:

- What happened to Racial Integration in the United States

Fellowship Year:

- 1990

McGeorge Bundy: How the Establishment’s Man Tackled America’s Problem with Race

McGeorge Bundy hardly guessed how long a journey he was beginning when he traveled to Philadelphia in August 1966 to address the annual banquet of the National Urban League. After drinks and dinner in the formal hotel ballroom, the new president of the Ford Foundation spoke for half an hour or so about what he called the problems of “the American Negro.” His well-dressed, integrated audience must have found it all a little bewildering. After all, as Bundy himself admitted, he had virtually no experience in the realm of race relations. Fresh from five years in the White House, where he had worked 12-hour days as special assistant for national security, Bundy had been so busy with Vietnam and other problems that he had scarcely had time to read newspaper accounts of the civil rights movement. McGeorge Bundy in 1967, while head of New York City Mayor John Lindsay’s special panel on school decentralization. (AP/Wide World Photos) Nor had Ford, or any other large foundation, shown much interest till then in the plight of blacks:

How a Campaign for Racial Trust Turned Sour

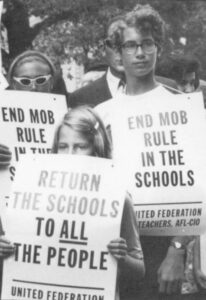

Glamorous young mayor John Lindsay had been in office all of two months when he threw down the gauntlet on the issue of civilian police review. The occasion, in February 1966, was the inauguration of a new police chief, a man known to be committed to civilian review. “I intend to offer new solutions,” Lindsay declared over the airwaves, “and every one is going to disturb the tired, self-perpetuating bureaucratic ways of the past. Jobs will change. Deals will be canceled. Fat and easy lives will be disrupted.” Police in the audience bristled, but lots of other New Yorkers cheered, thrilling to the mayor’s boldness and his take charge reformism. I cannot promise you a peaceful administration,” he continued. I cannot promise you that you will not continue to hear the howls of the power brokers…But I can promise you change and reform and progress. One of Lindsay’s most famous speeches, it caught everything that made him inspiring-and also bitterly resented-as mayor. Photographed on his first day as mayor in January, 1966, John V Lindsay

The Devastating Power of Racial Belligerence

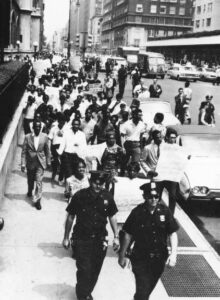

Sonny Carson is not the best known or even the most disruptive of New York’s freelance “black activists,” but he has proved the most painful thorn in David Dinkins’side. The two men’s names were first linked in the public’s mind in August 1989, just weeks before the Democratic primary that pitted Dinkins against Mayor Edward Koch. The jaded Bensonhurst slaying of black teenager Yusef Hawkins had set even the city’s nerves on edge and given Dinkins, who was promising to deliver racial harmony, a considerable advantage among both black and white voters. Then, on August 31, downtown Brooklyn erupted in a bloody racial free-for-all. More than 7500 demonstrators, most of them black, marched six abreast down the borough’s main shopping street. Carson led the angry but disciplined column, brandishing placards and chanting rhythmically: “Whose streets? Our streets! What’s coming? War?” The national Congress for Racial Equality organized demonstrations at the New York World’s Fair in 1964 to protest civil rights injustices and to show leadership to its more radical Brooklyn chapter. Private fair police drag